[Michael reviews work in a combination of interesting media by a young artist whose approach seems at once personal and political. — the Artblog editors]

BUT HERE GOD PUTS THE FLOOD

BUT HERE GOD PUTS THE FLOOD

This text, which appears in two of the installations in Bonnie Brenda Scott’s exhibition at James Oliver Gallery, comes from a poem written by the artist about natural disasters and the origins of devastation. The complete phrase from the poem reads: “The tide comes in from all sides, but here god puts the flood.”

I asked Scott about this, and she explained:

“God puts the flood in you and lets you go about destroying whatever you care about all on your own, by being careless or reckless or out of control.”

I first thought that the phrase was a reference to Genesis, because the work does, in certain respects, suggest manmade catastrophe. Although Noah is nowhere to be found, the light that shines through Scott’s work substitutes for Noah and ends up saving the day.

Pieces to defy frustration

There are other intriguing textual elements included in Scott’s work. The title of the exhibition itself, The Year of No, is somewhat enigmatic, particularly in the face of one of her pieces, which consists solely of the word “YES”. When I asked Scott about the title, her response suggested that her work reflects and embodies a measure of personal frustration, and at the same time, in some way, compensates for that. Another piece in the exhibition, in neon, spells out “THE WIND COMES”.

The Year of No includes 13 of Scott’s untitled, unique creations: mixed-media installations that combine sculptural as well as pictorial elements, many of which contain loopy neon piercings.

As Scott describes them: “The illuminated plexiglass pieces each have a painting on Mylar embedded in them. The paintings are done with an airbrush and a series of stencils I create based on a 3D image. The pieces of plastic surrounding the paintings are each cut with a variation of the same image. Everything is made using a laser. The colored plexiglass comes that way–florescent plexiglass will edge-glow on its own, wherever it’s cut.”

And indeed, the installations glow. Moreover, they seem to seem to change as you walk around them.

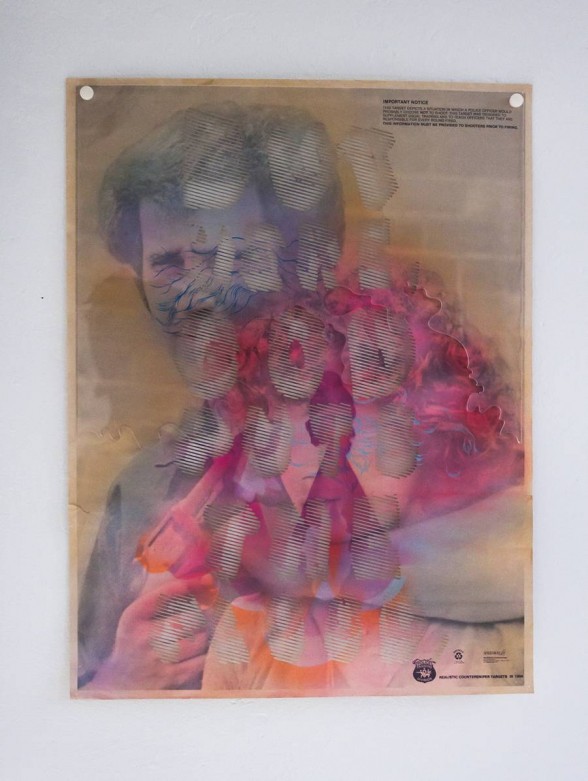

Two of the most powerful pieces in the show are built upon airbrushed drawings on target practice off-set prints. Although they are untitled in the exhibition, I understand that they are named “For Those In Peril I & II”. One of the off-sets is titled “Realistic Situation Target No. 522”. The other: “Realistic Countersniper Targets”. Scott’s treatment of them, of course, is anything but realistic. In “Realistic Countersniper Targets,” a man grips a hostage in a choke hold and points a gun to her head, and “BUT HERE GOD PUTS THE FLOOD” is superimposed upon the image. Remember: “God puts the flood in you and lets you go about destroying whatever you care about all on your own, by being careless or reckless or out of control.” Scott, I think, underestimates the political power of her work.

“Realistic Situation Target No. 522” was the strongest piece in the show. A yellow transparency superimposed over the darker human target glows brilliantly, without electricity, overcomes the forbiddingness of the image, and dominates the room. “BUT HERE GOD PUTS THE FLOOD” is missing from this piece, but it is there in spirit, and the magnificent light shines through.

Bullets and bright diptychs

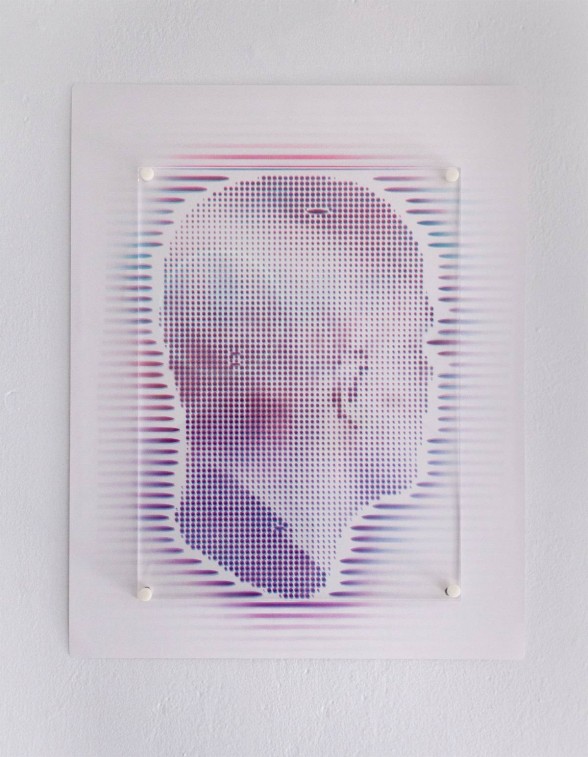

Another very powerful piece in the exhibition–again untitled here, but otherwise named “She’s So Unusual”–presents a man’s head in profile, but turning slightly away from the viewer. The piece is composed of hundreds of small circles in purple-blues (like candy buttons, but beautiful ones) below interesting patches of shading, and the head is surrounded by incoming projectiles, almost missiles, of the same hues. There may be bullet holes in the man’s head.

There are a number of unhinged diptychs in the show, some abstract, some abstractly figurative. In one compelling pair, female busts in profile face away from each other. Scott uses dimpled patterns in the plexiglass to create an ethereal effect, and the contrasting similarities and differences between the images are remarkable. I thought the more figurative of these installations worked as doppelgangers.

Lighthearted light-based works

In addition to my sense of the transformational role that light plays in Scott’s work, there is a lighter, colorful side here too, which mitigates her severity. In fact, many of the pieces in this exhibition first appeared in a previous sculptural installation amusingly titled The Most Beautiful Thing I Ever Saw In Life Was a Perfect Circle of Fire, or: There’s a Joke Here Somewhere, and It’s On Me. There is an appealing element of simplicity in Scott’s work, particularly in some of the minimalist neon pieces in the show. Scott has titled the one represented above “Call of the Void”.

In her statement presented at the gallery, Scott describes her “efforts to visualize the universal connection between all forms of matter and energy, and to remain aware of constant change.” I’m not sure that she always accomplishes that, but she’s clearly on to something here.

Bonnie Brenda Scott is a young artist, now living in Brooklyn, who was associated for many years with Space 1026 here in Philadelphia. She received an MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. We can look forward to years of interesting work from her.

The James Oliver Gallery is located on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia next to Mori Moto. Unfortunately, the gallery is inaccessible to anyone who is not able to climb four flights of steep stairs up to the top floor of the building. Resting couches on each landing help out, but not much. The gallery’s hours don’t help either. It is open Wednesdays through Fridays between 5 pm and 8 pm and Saturdays from noon to 8 pm.

In this case, the excursion up the stairs is well worth the effort if you can make it.

The Year of No by Bonnie Brenda Scott is on display at James Oliver Gallery from Feb. 5, 2015 – March 25, 2015.