[Andrea praises two recent volumes detailing Matisse’s cut-out works, and 15 of Picasso’s early Cubist works, respectively, and enjoys the depth provided by the second book’s e-book format. — the artblog editors]

Art historians working in museums, as opposed to those in academe, are always aware that the artworks they deal with are things–embodied, resulting from a series of decisions made by the artist, and subject to subsequent change. The literature on art, both academic and in museum catalogs, has not always acknowledged this physical reality, but fortunately it is becoming more common. Two recent publications from the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) explore the physical aspects of artworks in different ways.

Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs

Karl Buchberg et al., eds. (Museum of Modern Art, New York: 2014), ISBN 978-0-87070-915-9

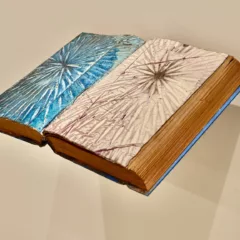

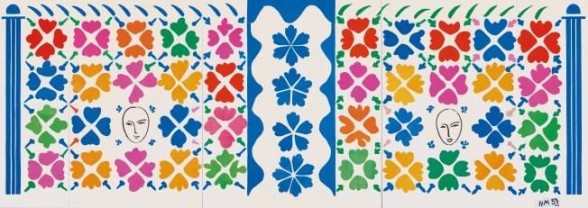

This impressive exhibition catalog records and analyzes the extraordinary body of work that Matisse produced during the last decade of his life. The cut-outs were created in an entirely new medium that required a novel means of production and presented formal challenges that the artist had not faced in his paintings.

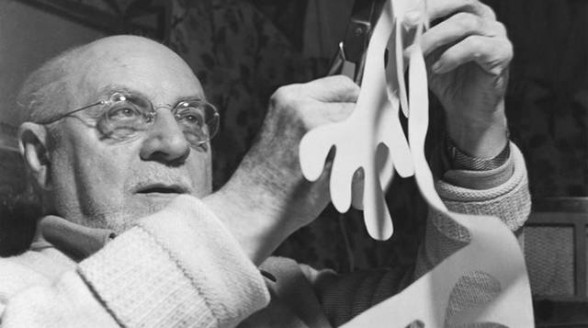

The change in materials and working method was a response to illness, which confined him to bed. Working with assistants who painted paper to the artist’s specifications with gouache (an opaque, water-based paint), Matisse cut out shapes with large tailor’s scissors and instructed assistants where to pin them to his studio walls. Once he was satisfied with the arrangement, an assistant recorded their locations so that they could be glued to canvas, which was then stretched for hanging.

Intimate insight into Matisse’s life

Not only are the cut-outs well illustrated, but their development is documented by a very large series of photographs taken by multiple visitors to all three of the artist’s studios. They reveal the extent to which the cut outs had a provisional life as decoration for the studios before their compositions were finalized with glue. Matisse referred to the cut-paper forms pinned to the studio walls as his “little garden”; when he could no longer swim in the ocean, he created a swimming pool that he hung on his dining room walls. The photographs reveal just how intimately the artist lived with this body of work, hung amidst furniture, drawings, and vases of flowers, both in studios and in furnished living spaces.

The book contains nine essays in which multiple authors discuss the cut-outs’ origins, development, their changing evolution as part of his studio and household environments, their relationship to the rest of his work, and their subsequent reception. One essay addresses Matisse’s earlier use of cut paper as a means of planning set designs for the Ballet Russe, the Barnes Murals, and the 20 images reproduced by “pochoir” (stencil) as the album, Jazz.

The large body of cut-outs produced for decoration of a new chapel at Vence is documented and analyzed, and an article by three conservators covers Matisse’s materials and techniques in detail and in very clear language. This book would be a wonderful introduction for anyone who isn’t familiar with the range of Matisse’s cut-outs, and is a welcome and valuable resource for those who know them.

Picasso: The Making of Cubism 1912-1914

Anne Umland and Blair Hartzell with Scott Gerson, eds. (Museum of Modern Art, New York: 2014); e-book

This e-book-only publication catalogs 15 of Picasso’s early Cubist works: both the cardboard and metal versions of “Guitar,” two collages on canvas, and 11 works on paper, which include both drawings and collages. It will be invaluable for anyone interested in early Cubism and for all serious students of modern art. While the entries include the usual curatorial essay, conservation notes, provenance, exhibition history, and references, they also provide considerably more in the form of illustrations. All the works have visual material that only the digital format can provide–they enable more detail, multiple views, and considerably more illustrations than would ever end up in print. This has totally convinced me of the potential value of e-books for art history.

This e-book-only publication catalogs 15 of Picasso’s early Cubist works: both the cardboard and metal versions of “Guitar,” two collages on canvas, and 11 works on paper, which include both drawings and collages. It will be invaluable for anyone interested in early Cubism and for all serious students of modern art. While the entries include the usual curatorial essay, conservation notes, provenance, exhibition history, and references, they also provide considerably more in the form of illustrations. All the works have visual material that only the digital format can provide–they enable more detail, multiple views, and considerably more illustrations than would ever end up in print. This has totally convinced me of the potential value of e-books for art history.

E-books’ art appeal

The format enables both guitars to be rotated 360 degrees, and all the works on paper to be seen unframed, recto and verso. All the entries include additional technical photographs, such as raking light views, ultraviolet, infrared, and radiographic studies whose value is described in clear language in the conservation essays. There are also three short and useful videos about the construction and comparison of the two “Guitar”s by conservator Scott Gerson.

A serious scholar might arrange access to one or two of these works at the museum, but would not easily examine all 15. Now, even students studying far from the originals will be able to see exactly how the pieces of twine representing the frets of the paper “Guitar” are knotted; how tenuously the pins attach the various papers of “Bar Table With Guitar,” and the shadows cast by collaged elements that do not lie absolutely flat; Picasso’s various use of brushes, palette knives, and instruments to incise paint; exhibition labels on the versos; and cracquelure that the artist induced, as well as that occurring with age.

The exhibition histories of the works are accompanied by a wealth of rarely-published photographs recording gallery installations. Some were taken before the works entered the museum, and all convey information as to how works were hung and juxtaposed. They also document changing hanging conventions at MoMA.

Note on the format: I had some initial difficulty navigating the book, and had to learn how to enlarge the images without jumping to another page. That may simply reflect my own inexperience. Also, since I suspect most readers will use this sort of work on a computer rather than an e-reader–to be able to see the images at a decent size–it’s a shame it wasn’t designed in a format that scrolls, rather than flipping from page to page. The one institution I know that has mastered the dual hard copy/on-line format is Culture 24, in its reports.