[Michael L. brings us a cadenced review of an intricate installation whose soaring strings may conceal a message for future generations. — the Aartblog editors]

The heart of Douglas Irving Repetto’s installation at Marginal Utility, which is composed of seven elements of thick white cotton string that crawl through a series of hooks and mechanized spools, is the kill site, which represents the locus of an animal’s decomposition in a forest. At the kill site, like the return of animal matter to the earth (and beyond), random codes of color are imprinted upon the strings as they pass through the site, and the strings then carry those codes throughout the universe of the installation. One is reminded of the phenomenon that we all are the remnants of stars.

Mesmerizing mechanics

The images included here capture the installation’s playground-esque shape. In fact, each of the seven elements of the installation consists of a single long string (actually sections of string knotted together) that eventually passes through the kill site, where dripping acrylic ink creates random shapes and patterns of color upon its surface.

Encrypted messages, or music

What the images fail to capture is the slow, vibrating, lifelike motion of the installation and the cascade of sounds generated by the motors, all punctuated by claps of a small piece of plywood against the wall at the kill site, part of the process that rotates the plate that houses the dripping ink containers as the strings pass beneath it. The voice of the ink robot.

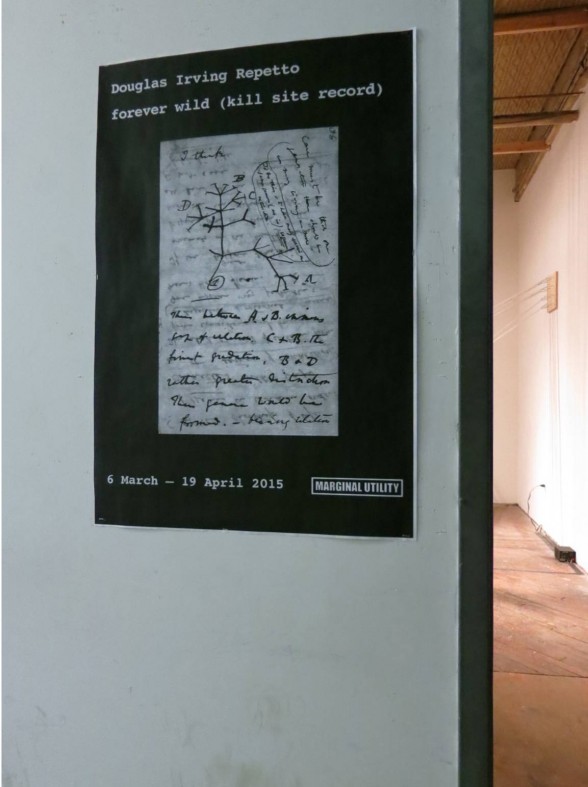

As time goes by, each of the seven strings slowly and repeatedly pass through the kill site, and the color codes upon each of them are elaborated. I suppose at some point in the future (certainly beyond the life of the exhibition, perhaps at the end of the world), each string would be fully saturated, and black. It occurred to me that these random color patterns could somehow be digitized and played as music or translated into a language of some sort (“as if a magic lantern threw the nerves in patterns on a screen”).* Seven streams of undecipherable sounds or symbols; an evolving, ever more complex symphony or language. Perhaps the same song played by the decomposing animal’s DNA as it finds its way into new life forms. The show poster, pictured above, aptly highlights Darwin’s tree of life.

One of the notes for the installation refers to “undeciphered Inca khipu (knot) records.” During the Bronze Age, Inca civilizations in South America encoded and recorded information on cryptic knotted strings called khipu. Historically, khipu were believed to be used to calculate and record numbers. Now, however, some anthropologists believe khipu may have been used as a form of writing narratives about the Incan empire. What is Repetto trying to tell us?

With the tragic deforestation of the Earth, Repetto presents us with a simulated kill site: forever wild (kill site record). One of the notes for the exhibit refers to this installation as Repetto’s “second in a series of speculative machines that generate artifacts related to (future) obsolete natural processes.” And another: “Generative mementos from a kill-free forest.” The undecipherable narrative of “forever wild, the kill-free forest” may be the story of the natural world that humans are destroying today.

Genesis and destruction

And then there is the number seven. Seven elements of the installation. Seven strings. Seven motors. Seven ink containers. Seven glass magnifiers (used to examine the strings). So many theories of seven, here it may be sufficient to stop with Genesis: six days to create the heavens and the earth; the seventh to rest. And later the flood.

There is, perhaps, an eighth element to Repetto’s installation: gallerists David Dempewolf and Yuka Yokoyama themselves, who become the caretakers of the machine and our guides. Indeed, there may be a connection between the concept of marginal utility, which Dempewolf and Yokoyama borrowed for the name of their gallery from Peter Singer’s application of the concept to eliminating hunger in the world, and Repetto’s work. Perhaps the message here is that we can destroy the Earth, or together, we can save it.

I’ve quoted Prufrock above. Just to reflect a measure of uncertainty about my slightly far-out meditations on Repetto’s work, perhaps I should note that the stanza in which that quote appears ends:

“That is not it at all,

That is not what I meant, at all.”

Douglas Irving Repetto is an artist and teacher whose work includes sculpture, installation, performance, recordings, and software. He is the founder of a number of art/community-oriented groups, including dorkbot: people doing strange things with electricity; ArtBots: The Robot Talent Show; organism: making art with living systems; and the music-dsp mailing list and website. Repetto teaches at Columbia University, where he is the director of the Sound Arts MFA program in the School of the Arts and Computer Music Center.

Marginal Utility is open weekend afternoons. Go see the exhibit and speak with the guides–it is an intriguing experience.

* From The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, by T.S. Eliot

forever wild (kill site record) by Douglas Irving Repetto at Marginal Utility runs from March 6 – April 19, 2015.