[Marvin explores celebrated photographer Paul Strand’s Mexican photogravure work and Taller de Gráfica lithographs by Francisco Mora, Elizabeth Catlett, and others. The two shows offer diverging views–micro and macro–of Mexico’s beauty, struggle, and daily life. — the Artblog editors]

Drug cartels, mass murders, political unrest, and spring breakers…? Beyond the current turbulent state of Mexico, we often forget the country’s period of artistic explosion in the early to mid-20th century, which contributed to the modern era.

Mexico during a critical time

Two shows, at two different venues, look at Mexico’s people and culture during the 1930s and 1940s. Paul Strand: The Mexican Portfolio is on view at Arthur Ross Gallery at the University of Pennsylvania, while Elizabeth Catlett: Art for Social Justice is being shown at La Salle University’s Art Museum. Both exhibitions also feature the complete lithographic portfolio Mexican People: 12 Original Signed Lithographs by Artists of the Taller de Gráfica Popular, Mexico City (1946).

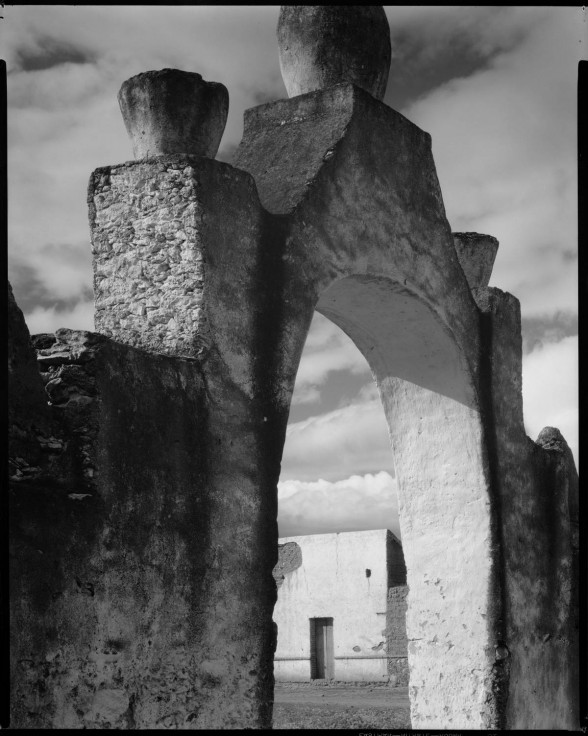

In late 2014, visitors flocked to see the Paul Strand (1890-1976) retrospective at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. We were given a brief look at some of the photographs he took, starting in 1933, when he traveled throughout Mexico. Invited by Carlos Chavez, director of the Fine Arts Department of the Secretariat of Public Education, Strand explored Mexico’s small towns, churches, religious icons, and the country’s people for two years. Strand, like the artists working at the Taller de Gráfica Popular (The People’s Print Workshop), sought to reimagine post-revolution Mexico and “to establish a modern national culture that would capture Mexico’s unique character.”

The end result was over 175 photographic negatives and 60 platinum prints, of which 20 were chosen to be part of the portfolio Photographs of Mexico (1940). However, the current show, organized by Syracuse University Art Galleries at Arthur Ross Gallery, displays the 1967 re-released portfolio, featuring photogravure impressions. Photogravure is a photomechanical printing process that is similar to making an etching or an engraving on a metal plate. Yet, photogravure plates are made light-sensitive, exposed to a film negative, and then etched in an acid bath.

For Strand, reprinting the images as photogravures allowed for crisper tones and depth–an idea first explored in his early photographs, which convey the dramatic qualities of Pictorialism. Strand was highly praised for his keen eye and his sensitivity to Mexico’s rich past and dynamic changing atmosphere.

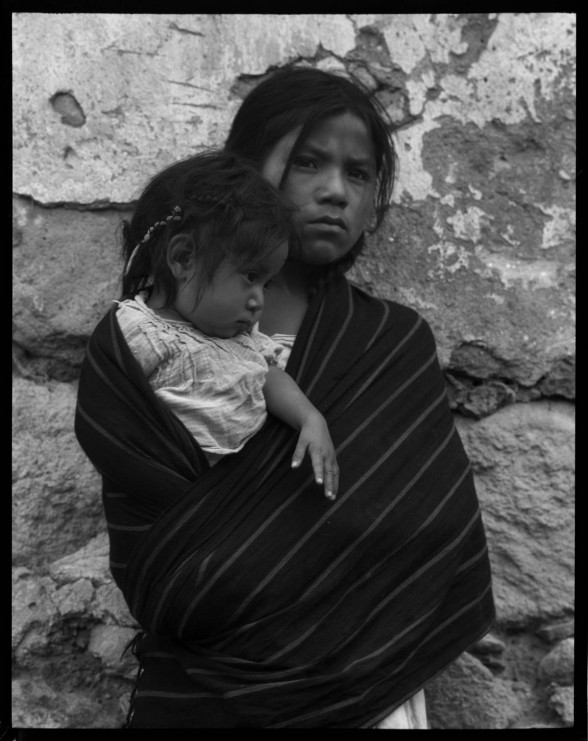

Idealism versus everyday life

The intimate Arthur Ross Gallery space is an appropriate setting for viewers to contemplate and absorb the various images. Each photograph is carefully constructed, almost theatrical, and monumentalizes the subject portrayed–an untouched, sublime landscape, a Spanish Baroque-style gateway, religious objects, or everyday townpeople. By printing these in black and white on woven paper, Strand concentrates his efforts on the subject’s natural tonal values and contrasts, which allows viewers to see every detail: the rough textured surfaces of a stone structure, a child’s dimples, the drapery on a farm worker’s shirt or a woman’s shawl. Strand gives us a glimpse into the lives of Mexico’s people. There is something sentimental about each of these photos, revealing a culture shaped by heritage, tradition, values, and hard labor.

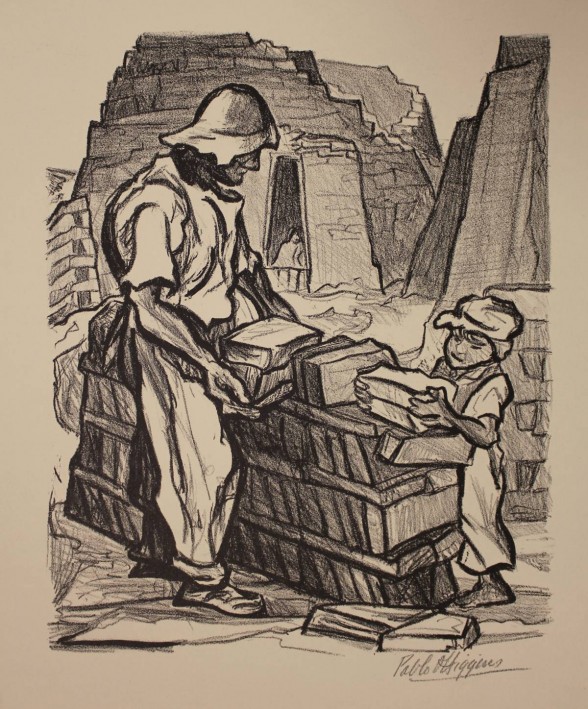

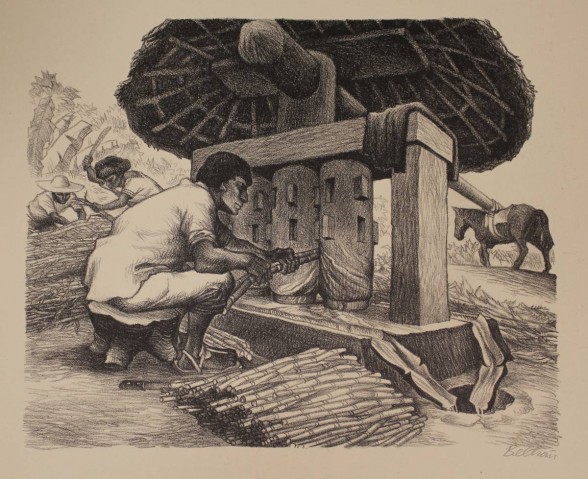

Interestingly, all 12 lithographs from the Mexican People portfolio hang alongside Strand’s photos. In lithography, the prints are usually made by drawing the image with a grease crayon onto a stone, such as limestone. The lithographs juxtapose Strand’s idealized and romantic scenes. Whereas the photos do not show people at work–their travails maybe only evidenced in their shabby clothing–the lithographs depict men, women, and children processing various products.

The lithographs feel more authentic due to the active, documentary-like narrative nature of each piece. There is so much going on in the foregrounds as well as in the backgrounds. Each print reads like a film storyboard. People are making pottery, grinding sugar cane, plowing with mules in the fields, stacking bricks, grinding maize, or selling wares in a marketplace. This dichotomy between the photos and prints reveals the divergent views and underlying agendas of Mexico’s people during the country’s rebirth.

Catlett and Mora

The Taller de Gráfica Popular, which launched in 1937, was a meeting place for artists interested in sociopolitical art who were also inspired by the ideologies of the famed Mexican muralists. These artists–both men and women from different political parties and classes–used the graphic arts as propaganda to expose the social realities of Mexico’s poor and working class. Printmaking allowed for these images to be readily available, easily disbursed, and inexpensive to produce. Yet, unlike Strand’s photos, the work in Mexican People is more accessible and impressionable to the period.

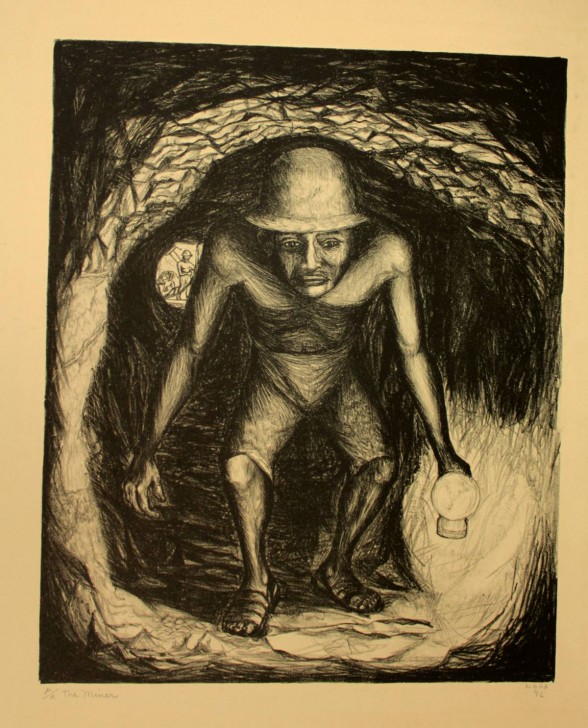

From all the prints, the most powerful is Francisco Mora’s “Silver Mine Worker”(1946). Mora’s central figure is a partially clothed worker who only wears a helmet, shorts, and open-toed sandals. His only light source comes from the lantern he holds in his right hand, which guides the miner into the dark abyss as he moves away from the entrance. The miner’s arching body and the dark spiral framing him together create a claustrophobic effect. At closer observation, you can see the physical incisions Mora made throughout the lithographic stone’s surface before running it through the press. This adds to the raw reality of broken stone and the cuts inflicted onto miner’s flesh. Despite the print’s unnerving effect, there is a literal sense of light at the end of the tunnel, quite possibly suggesting that hard work will eventually pay off.

The show is complemented by photographs from Manuel Álvarez Bravo, who also captures Mexico’s customs, and the documentary An Artful Revolution: The Life & Art of The Taller de Gráfica Popular (2008), which features artists involved at the Taller, including Elizabeth Catlett.

In celebration of what would have been Catlett’s (1915-2012) 100th birthday, La Salle University Art Museum has put together a small exhibition of some of the artist’s prints, mixed media, and sculpture. Elizabeth Catlett: Art for Social Justice provides a brief overview of the artist’s long career. The work is drawn from the university’s collection, as well as private collections and other museums. Catlett, an American-born artist with African-American and Mexican ancestry, was part of the Taller de Gráfica Popular between 1946 through 1966. There, she met future husband Francisco Mora, whose work, along with that of other artists featured in the Mexican People portfolio, is displayed in an adjacent gallery.

In 2001, Moore College of Art and Design displayed both Catlett’s and Mora’s prints from the 1940s and 1950s as part of a citywide programming initiative sponsored by the Philadelphia Print Collaborative. That year, the organization was celebrating an exhibition of African-American WPA-era printmaker Dox Thrash at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The Catlett show exemplifies the university’s mission: social justice for all. Catlett’s work represents the oppression and inequalities burdening people of color and women. From her days at the Taller well into the civil rights era and beyond, Catlett’s work is versatile in medium and style, but always carries the same powerful message. She once said, “I have always wanted my art to service my people–to reflect us, to relate to us, to stimulate us, to make us aware of our potential.” Creating work well into her 90s, Catlett examines common themes in the history of art, yet also explores ideas of multiculturalism.

The university museum has used Catlett’s work as part of numerous educational programs targeted at Philadelphia K-12 public school students. The choice of such a diverse audience demonstrates not only the growing need of art education in urban city schools, but our evolving society in the 21st century.

Paul Strand: The Mexican Portfolio is on view at Arthur Ross Gallery, University of Pennsylvania through March 29, 2015.

Elizabeth Catlett: Art for Social Justice is on view at La Salle University Art Museum through June 4, 2015.