[Alex comments on a show comparing outsider artists’ work with that of “established” artists. He notes that the show’s formal, quasi-scientific arrangement mostly puts the pieces on par with each other. — the Artblog editors]

Do artists with formal education, fame and cultural prestige necessarily create “better” work than artists working with limited access to institutional support and resources? As somebody who studies and writes about art, I often face the aggravating experience of hearing people say, “My kid could make that!” when viewing modern or contemporary work. I now give the stock response, “But they didn’t, and that’s why we’re looking at it on a museum wall.”

My patience may be short, but the new show in the Korman Galleries of the Main Building of the PMA takes time to show not only the merit of artists that have existed outside of the cosmopolitan “art world proper,” making work out of unorthodox materials and subjects, but also showing their influence and congruency with innovations in modern art, particularly collage and assemblage.

Formal arrangement

This show mainly consists of small, framed works, with the exception of the formidable “The Sun: Tarot XIX” by the little-known Jess Collins (1960). This work–a heady collage utilizing human anatomical diagrams and lithographs of ancient civilizations–is the first piece you see when entering the space. The collages and drawings run in a more or less consistent line at eye level around the galleries, arranged so that a work by an outsider is almost always placed next to an artist whose name we are all familiar with: Picasso, Arp. Some of the works by the outsider artists may be familiar, as they were featured in the 2013 show Great and Mighty Things: Outsider Art from the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection.

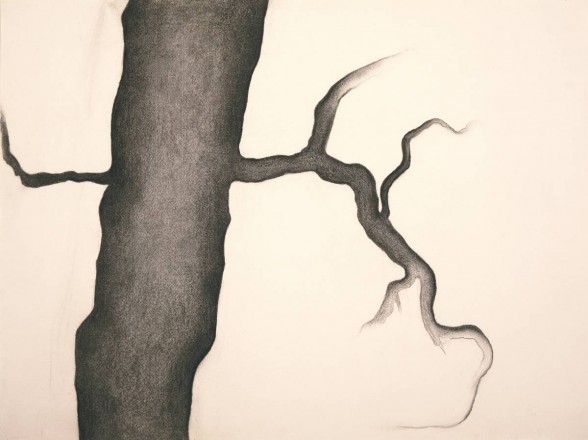

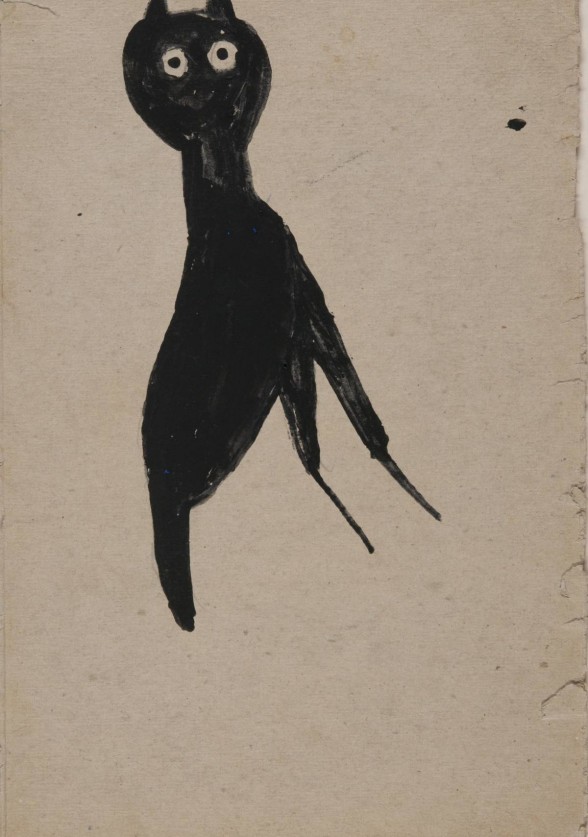

The way in which these pieces are displayed beside one another suggests a formal analysis of each pair. Pieces that are similar in scale, medium, and even color are categorized in a cold, scientific manner, making it difficult for the viewer to distinguish who is outsider and who is “insider” (very much the point of this exhibit). For example, a minor work by Georgia O’Keeffe, a watercolor of a bare tree’s silhouette, is paired with Bill Traylor’s “Owl” (1939-42), a watercolor depiction of the bird also done in black on a neutral background.

Certainly the works were wrought by different hands, one like a Neolithic totem while the other exudes an East Asian lyricism, but upon first glance, the training or prominence of each artist could very well be on par! It is only when you read the labels that there is any distinction. O’Keeffe is O’Keeffe, while Traylor (who made work around the same time as O’Keeffe) is revealed to have been a former slave who spent his later years homeless in Montgomery, Alabama, making work on scrap cardboard.

Troublesome labeling

Some comparisons proved to be problematic; the works were physically similar, but the labeling diminished the visionary spirit of the outsider artist. The example that sticks out in my mind was the pairing of a mid-19th-century untitled “Shaker Inspirational Drawing” by Sarah Bates, and an untitled drawing of the same medium (colored pencil and graphite) from 1965 by Frank Jones. While both works possess geometric, architectural foundations containing supernatural themes, Jones’ lifelong belief in his “second sight” is diminished by his characterization as an “uneducated black man” and prison inmate. Had there been a description for Bates, would her spiritual experiences have been tied to her white womanhood?

And was she not an outsider artist of sorts? What was her training?

One of the highlights of this show for me, personally, was seeing a Paul Thek in person, specifically “Time is a River” (1988). Thek utilized the personal mythology and nontraditional media of visionary artists in his expansive, complex oeuvre, and it showed clearly in this late-career collage of newspaper, acrylic, and gesso. Another must-see is the work of Susuan Te Kahurangi King of New Zealand, an artist whose muteness marked her as an outsider. Her drawings articulate the humorous and disturbing aspects of cartoon characters like Bugs Bunny.

Though it may take some time for some, the pieces in this show (by both recognized and recently considered artists) show that this art is not mere child’s play, but examples of serious lifelong artistic pursuit, experimentation, and resourcefulness.

Interfaces: Outsider Art and the Mainstream is currently on display at the Korman Galleries 121-123 in the Main Building of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.