[Evan is deeply moved by the message of a multi-artist photography show, which turns its lens on those affected by Pennsylvania fracking. — the Artblog editors]

The Marcellus Shale Documentary Project at Philadelphia Photo Arts Center is an earnestly executed look at Pennsylvania’s ever-deepening problem with oil and gas companies and their “fracking” method of extraction. Noah Addis, Nina Berman, Brian Cohen, Scott Goldsmith, Lynn Johnson, and Martha Rial all approached this mammoth task in equally sensitive ways, inserting themselves into the communities and the personal relationships of those affected by big-business negligence.

Struggle hits close to home

The project began as, and still is, an activist project as well as a photographic one. Centered in Pittsburgh and funded by major supporters such as the Heinz endowment, the group seeks to not only educate the public about rightable wrongdoings on the part of oil and gas companies, but create an archive along the way. All of these photographers are successful in their own right; they’ve been published everywhere from The New York Times to National Geographic. The project has morphed and moved around a lot recently, as well as been displayed in spaces all over Pennsylvania.

A few icons appear in every section of the show–aggressively worded picket signs, tap water lit on fire or bubbling an unnatural hue, forlorn farmers forced to give their animals store-bought water. Often, those victimized by the gas companies are placed in the frame with those who benefit, whether it be a Harrisburg lobbyist or a farmer who agreed to let Shell use his land. The relationship depicted between these two groups is as toxic as the water coming out of the tap.

Another photography exhibition I recently saw and reviewed, Zoe Strauss’ Sea Change at Haverford College, shared a number of aesthetic elements both in the work and in display. In both cases, tragic circumstances befall an unsuspecting and under-aided local population–they are left to mostly fend for themselves, and resentment toward everyone accountable reaches a boiling point. They include similar types of images–the powerful perpetrators (whether natural or manmade) and the aftermath of their crusades, and the everyday heroes who bear the brunt of sustaining their lives and their communities. Contained in neat frames and organized in clean white galleries, their suffering is served to us in individually signed and sealed packages.

Pictures can make us feel closer to photographic subjects and their circumstances. They can lend false senses of proximity, even if the empathy is real. The more time I have had to think about these two exhibitions and their approaches to discussing injustices, the harder time I have objectively critiquing their content.

This is a problem for me. The struggles of those victimized are beyond what I ever have had to handle. These images depict the systematic dismantling of communities and livelihoods for the sake of monetary gain. This is literally happening from the ground up. These are relevant and pressing issues that do not evaporate just because we leave the gallery. Activism is needed, and awareness is key. At a certain point, aestheticizing this suffering seems futile. The traditional gallery setting doesn’t feel like the place where this work can make the most difference. The gallery just doesn’t do it justice–it needs to persist in a more practical setting as well.

Defining your own allegiance

The varying styles of the participating photographers sometimes create a productive dialogue between the walls of the gallery, and sometimes fall flat. Lynn Johnson contributes the only black-and-white work to the show, located in the gallery entryway. The starker, more graphic quality of her work contributes to the melancholic environments she worked in.

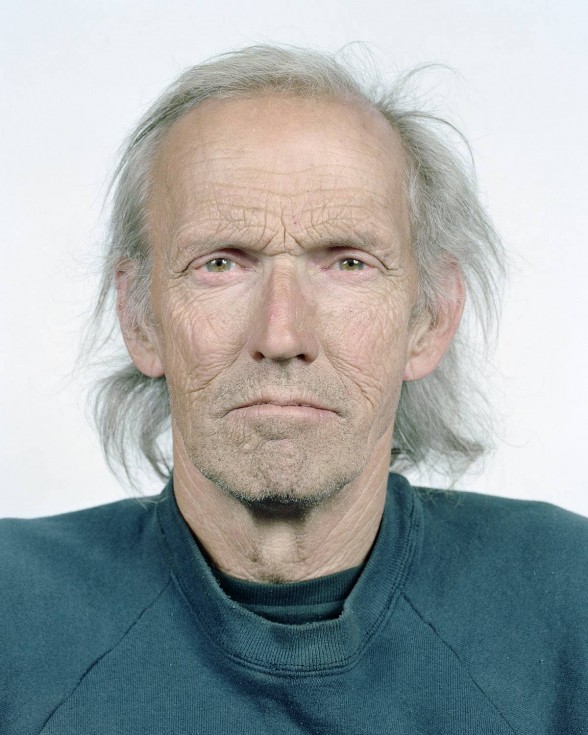

Sol Mednick Gallery. Field Notes: Fred McIntyre poses for a portrait at his home in Connoquenessing Township, PA on 04/30/2012. McIntyre, who has lived in his home for 20 years, claims that his water turned purple and foamy after several Marcellus Shale gas wells were drilled in the area in January of 2011. He and his family now drink only bottled water.

Noah Addis’ work is the most varied, including everything from extremely large portraits of local residents to deadpan landscapes interrupted with pipes or drills. The portraits are confrontational to the viewer because of their size as well as the unflinching faces of their subjects. I’d like to see if a gas company executive could walk through the gallery and keep his composure.

The works of Scott Goldsmith, Nina Berman, and Martha Rial visually parallel each other. Glossy color images in the documentary style depict a variety of subjects. A few individual images stand out, but I find this work to be the least gripping. Martha Rial’s image of volunteers working at an oil and gas safety company stand at a convention makes a sharp contrast to the aforementioned images of suffering. Young women in short-shorts and hard hats stand next to a smiling young man. I wonder where their allegiance in the conflict lies.

Open Lens Gallery. Field Notes: Having no clean well water, Simons and Lamphere give their horses bottled water to drink. They claim their water was contaminated by nearby gas-drilling activities, causing their daughter to be sick and their animals to die. Monroeton, Bradford County, 2011.

If approached from a purely visual angle, the exhibition fails to move me as much. What is important in this situation is to understand the underlying purpose of the exhibition and its social and political ramifications. The efforts of the subjects and the photographers should encourage activism to persist and make it harder to erase the faces of the afflicted. The collected work should act as a call to action–born in the gallery, bouncing out the door, and into the collective conscience of the public. The gallery is a fine place for activism to start–as long as it isn’t allowed to die there.

Marcellus Shale Documentary Project at Philadelphia Photo Arts Center until May 30th, 2015.

Evan Paul Laudenslager is an artist and writer based in Philadelphia. He is a graduate of Tyler School of Art.