[Andrea offers brief reviews of two books she recently enjoyed, each very different. One focuses on how light–in its many incarnations–appears and is used as a tool in African Diaspora visual practices; the other on artists’ interest in history and its artifacts. — the artblog editors]

Krista Thompson, Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practice

(Duke University Press, Durham: 2015) ISBN 978-0-8223-5807-7

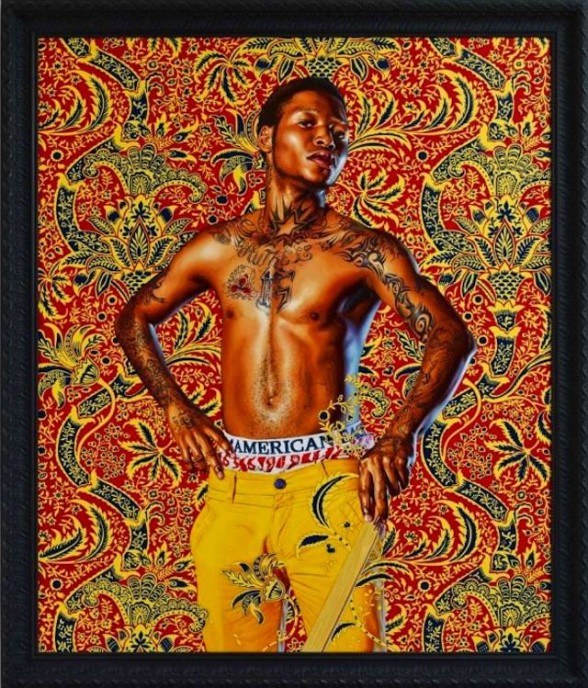

Krista Thompson explores the common use of light, shine, and “bling bling” as a means of self-fashioning and collective agency by African-American, Bahamian, and Jamaican youth culture. She also traces these effects in the work of contemporary artists, including Kehinde Wiley, Louis Gispert, Paul Pfeiffer, and Hank Willis Thomas. Her book reveals a sophisticated understanding of these effects that both the young and the artists employ with intentional irony, manipulating means that the wealthy and powerful have long used to confirm their status, and which the corporate world exploits for sales.

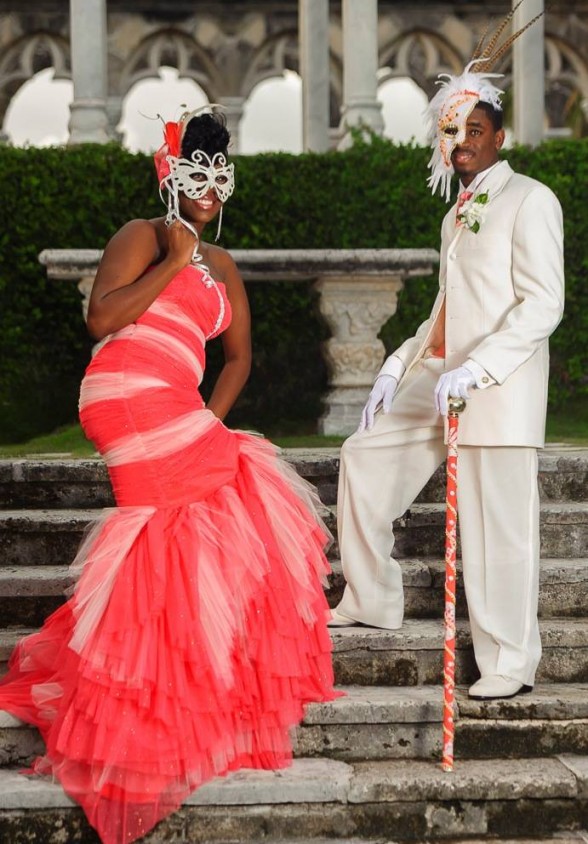

Thompson looks at the contribution of photography, video, and the Internet in communicating visual ideas among groups, and mines material that has been beneath the notice of art historians, visual culture scholars, and writers on the African Diaspora. She investigates street photography in front of painted backgrounds; Jamaican dancehall culture conducted in the blinding light of video cameras and the skin bleaching that has become associated with it; Bahamian high school proms where couples have arranged for groups of “paparazzi”–not to photograph them, but to create the effect of celebrity in the light of the cameras’ flashes; and the visual manifestations of hip-hop culture, including dress, promotional videos, printed materials, and album covers.

Other authors have suggested hip-hop music as an essential influence on the artists named above, but Thompson reminds us of skills particular to art history–that of understanding the meanings and sources of visual conventions. These are a more convincing source for artists’ visual language than the music alone. This is a remarkable piece of scholarship, complete with voluminous footnotes, and is particularly clearly written–despite its mouthful of a subtitle.

Dieter Roestraete, ed., The Way of the Shovel: On the Archaeological Imaginary in Art

(Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago with University of Chicago Press: 2013), ISBN 978-0-226-09412-0

The theme of this thoughtful exhibition catalog is the recent interest that many significant artists have taken in history and historical artifacts. As exhibition curator and Senior Curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Dieter Roestraete, puts it: “One of the defining ironies of our time is that so much of the vanguard art production–the art that is most closely aligned with the boundary-pushing, horizon-expanding tradition of progressive culture, and with the avant-garde’s traditional claims to ‘newness’ in particular–should be so preoccupied, both in its choice of techniques, in both form and content, with the old, the outdated, the outmoded–with the past.” He distinguishes current artists’ historical consciousness from the “postmodern enthusiasm for citation and…cannibalistic appropriation of historical imagery…”

Roestraete discusses artists’ research in archives and historical collections, often focusing on the overlooked, the left-behind, and forgotten aspects of historical accounts; the ultimate subject of their work, he posits, is the act of remembering. He finds connections to vanguard traditions of resistance and criticality in their “digging up a past everyone else seems in a suspicious rush to leave behind” and offers several motivations for the historical turn that manifests itself after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the attacks of 9/11: distrust of the grand narratives of traditional history, rejection of the tendency to equate the stockpiling of meta-data with remembrance, attempts to capture aspects of everyday life that have disappeared in the new, post-Soviet Europe, and refusal of neoliberal complacency.

The more than 30 European and North American artists in the exhibition include Moyra Davey, Tacita Dean, Stan Douglas, Mark Dion, Cyrpian Gaillard, Gabriel Orozco, Anri Sala, and Hito Steyerl. The catalog includes a page-long essay on each artist followed by several full-color illustrations of works in the exhibition. It was clearly intended to attract detailed notice as an object itself–a distinctive and handsome one. Designed by James Goggin and Scott Reinhard, who variously acknowledge historical book production and cataloging, its colophon might have been written by an obsessive artifact registrar; it lists all the materials and methods of both contents and binding, noting that “the last remaining supplies of PS4885 Olive Green [buckram cloth] in North America wraps the spine and part of the face of the book, and that the endpapers are derived from rock stratigraphy illustrated in a 1955 geology text, which is thoroughly cited. An entire column is devoted to the nine (!) fonts employed, with a brief history of each.

The volume includes four further essays: Bill Brown discusses various differences between archaeologists and artists in examining the relationship between people and material culture; Sophie Berrebi suggests that “when examining the more recent incursions by artists into the field of history…the historiographical ‘critique of the document’ might offer useful suggestions…to interpret works by artists that appropriate forms of document production and presentation to unsettle historical narratives…”; Diedrich Diederichsen looks at post-WWII memorial culture and the “sculptural ideology critique” of a number of recent artists; and Ian Alden Russell addresses the 20th-century rift between art and archaeology, and various artists’ relationship to archaeology since the 1960s. The book lacks bibliography, but the articles are thoroughly footnoted; Roestraete’s contains an entire page of notes facing each page of text.