[Evan is drawn to several installations addressing prison life and the prison-industrial complex. One or two add new ideas to this often-explored subject area. — the Artblog editors]

Philadelphia’s historic Eastern State Penitentiary has added five new installations to its list of already phenomenal works (especially Karen Schmidt’s Cozy), highlighting the plight of mass incarceration on America’s past, present, and future. By default, the installations are immersive. They converse with the seriousness and the novelty of the former penitentiary itself–now a museum space that dances between kitsch and crowd-pleasing programming, and education/activism.

In collaboration with the City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, Jess Perlitz, Ruth Scott Blackson, Emily Waters, Jesse Krimes, and Eric Okdeh each reclaim a space in the confines of Eastern State. Many of the artists have themselves served time; therefore they share at least a partial understanding with the souls who inhabited the cellblocks until the prison’s closure in 1971. The penitentiary is infamous for housing the likes of bank robber “Slick Willie” and “Scarface” Al Capone, as well for instituting far-reaching solitary confinement and physical/psychological abuse that led to its demise as an institution. It has been a tourist destination as far back as the 19th century, hosting visits by the likes of Charles Dickens.

Subtle shine and incarcerated incantations

The first piece I found myself in was Ruth Scott Blackson’s “No Trace Without Resistance,” a cellblock whose peeling walls have been planted with gold-leaf paint chips. The light that cascades into the room from the opening in the ceiling causes the chips to glisten, forming what the artist calls a “shimmering constellation”. It immediately draws our attention to the beauty of the countless other less-shiny chips of paint peeling off almost every surface in the complex. Looking deeper, there is beauty hidden in plain sight. I imagine that being confined in a small room like this one would force the same kind of search for anything that stands out from the monotony. There is also a dichotomy of material here with the use of gold leaf–time is money, money is time.

Around the corner in Cellblock 8 is Jess Perlitz’s “Chorus”. At first, the work is easy to bypass, as it appears to be just another plaque outlining a notorious event or prisoner. Upon close inspection, it is in fact a collection of the recorded voices of prisoners from around the country. Each was asked to sing a song: one that meant a great deal to them. Each song is layered as the piece progresses, rising into an overwhelming and haunting crescendo.

The most striking aspect here is not the emotion–the sheer magnitude of personalities and human beings expressing their worth and individuality–but the fact that none of the prisons allowed the singers’ names to be released. As a result, each is labeled with a number and location of incarceration. Even in song, an exercise of freedom, individuals are made anonymous and quantifiable, highlighting one of the major downfalls of modern criminal justice in America.

Air and light and space and time

Jesse Krimes has already made news for his monumental work “Apokaluptein16389067” while incarcerated for drug charges. The work, mostly constructed from newspaper scraps and federal prison bedsheets over a 70-month sentence, places materialism and consumerism in the vision of someone with access to almost nothing.

Krimes planned the entire piece out in his head and built it in small segments, mailing each one home to his girlfriend and piecing them together upon his release. This was illegal for him to do on many levels, including destruction of federal property for the prison bedsheets. Originally, the mural was pieced together on a flat wall; in this incarnation, Krimes uses the mural like wallpaper for the cell, covering every surface except the floor. Although I have not seen the original in person, the work takes on a uniquely different tone when it literally surrounds you, engulfing you in its muted pastel colors and flying female figures. The walls of the cell expand; it feels far more dreamlike.

Eric Okdeh and the Mural Arts Program hang a selection of four small murals on the outside wall of a cellblock adjacent to the prison baseball diamond. The series, titled Beyond the Wall, is a yearlong project focusing on mass incarceration and its effect on the community. Okdeh worked with a group of 35 incarcerated individuals to produce the murals, which are now scattered across the city in particularly victimized neighborhoods. While most of the installations here focus on the prisoners and their reintegration into society, these murals are unique in that they also represent the struggles of the victims of the crimes that put these people behind bars in the first place. There is also an emphasis on education: the missing link that can address the causes of crime instead of its effects.

And for dessert…

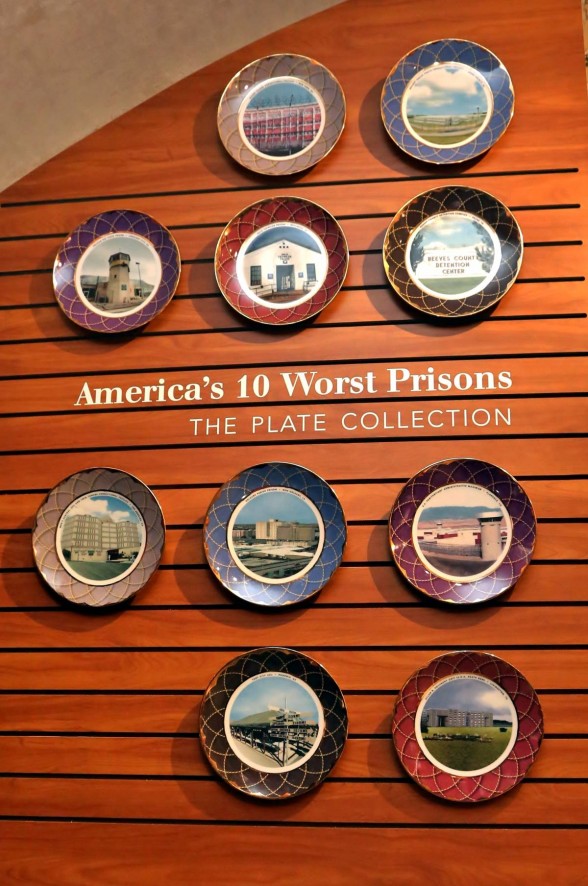

The final new installation resides in an unusual place: the penitentiary gift shop. While the very idea of having a gift shop in a prison seems odd, Eastern State does a good job of ensuring that you get a lot of critical social commentary with your commemorative keychain. Emily Waters’ piece America’s 10 Worst Prisons: The Plate Collection sneaks up on the viewer. Inspired by a decorative 19th-century dessert plate featuring Eastern State Penitentiary, the artist created 10 hand-painted porcelain plates featuring images of modern American prisons with reputations for high violence and human rights violation rates. In criticism of this attempt to make prison palatable, both the aesthetic and the placement couldn’t be more successful. The plates’ kitsch-y appeal invites initial curiosity, replaced by the sickening thought that you might be perpetuating the prisons’ aestheticized suffering.

The entire experience at Eastern State is a cocktail of fascination and guilt-inducing privilege-checking. Total disconnection from the stronger messages is impossible here; you can’t see the art without seeing its physical inspiration. In this way, the space perfectly suits the work and vice-versa. Many who simply go to see Al Capone’s cell or to use the free WiFi in the air-conditioned recharging room will be forced into introspection–hopefully the kind that sticks with you after you exit the prison gates, a pedestrian act for the free and the ultimate desire of those still locked up.