[Andrea explores the depth of artist Richard Tuttle’s work, which currently sprawls across several floors of the Fabric Workshop and Museum, but manages to stay restrained. — the Artblog editors]

Richard Tuttle is a magician whose work speaks modestly and softly about big ideas. He avoids emphasizing virtuosity of craftsmanship in order to demonstrate the unconventional possibilities he finds in the materials themselves. And Tuttle’s use of materials calls attention to what we, the viewers, might do with the same ordinary bits of wood, cardboard, cloth, string, ribbon, wire, or mesh–at least as much as it emphasizes what the artist has done with these homely bits of stuff. He asks us to look–at everything.

Everything is relative

The exhibition at the Fabric Workshop and Museum (FWM) through the summer combines five decades of Tuttle’s work from two recent exhibitions, organized by Magnus af Petersens–one at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, and the other at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, organized by Christina von Rotenhan. It is spread over seven galleries on three floors of the FWM, but if you only spend time with the works on the ground floor of the museum’s main facility at 1214 Arch St., you will gain a sufficient understanding of Tuttle’s extraordinary accomplishments. In work that ranges from painterly to sculptural to graphic, he demonstrates that art is about the potential of any materials as molded by vision and imagination, and that absolute size is irrelevant compared to the relationship of one thing to another: of relative scale.

The first gallery contains three irregularly-shaped, dyed canvas works from 1967-68 that forced the question of what constituted a painting. If Malevich stripped painting to its most elemental forms, and later monochromes confirmed that composition and incidental details are optional, Tuttle went further, asking whether a painting needed to be stretched, or regularly-shaped, and whether the wrinkles recorded during the dyeing process might substitute for marks made on the canvas’ surface. Or were these works wall-hung sculptures, flattened to two dimensions, hence not-quite conventional reliefs?

Tuttle has installed the exhibition himself, identifying each work or grouping with a number–sculpturally elaborated to form a miniature wall relief–that refers to a booklet which contains the usual label information as well as a poem by the artist, suggestive if not explicative of its content. He has rejected installation conventions, such as the height at which works are hung and the usual method of lighting artworks. His choices challenge viewers to think about those essential decisions that we normally take for granted.

Delicate, minimal works

The second gallery displays a series of wall drawings, begun with lines drawn in graphite on the wall itself, over which the artist stretched wire from a spool, to match the length and trajectory of each line. He attached the wire to the initial point of each drawing, and the memory of its coiled form caused it to distort, casting a variant in the form of a shadow. The three layers of drawing, wire, and shadow intermingle as the viewer walks in front of them, like ballet dancers in a pas de trois. On the opposite wall are a series of minute reliefs, each of which could be cradled in the palm. They are mounted on visible brackets that project from the wall, and here Tuttle’s unconventional lighting choices–with bright spots on the identifying numbers, but soft floods that cast raking light on the works–begin to make sense. The shadows are as integral to these reliefs as they are to the drawings across the gallery.

The entirety of floors two and eight exhibit wall and floor pieces. “Ten Kinds of Memory and Memory Itself” (1973), a series of drawings on the floor with string, suggests that the act of memory can make the impermanent more enduring than the supposed permanence of metal or stone, and the analogy with life is inevitable: “The dead live on in the hearts and souls of those who cherish their memory.”

“Third Rope Piece” (1974) caused a great deal of consternation when first exhibited for its suggestion that a three-inch piece of rope nailed to the wall was sufficient as an artistic statement. Tuttle’s poem about the piece suggests the complexity of his thoughts, despite his restricted means:

“Not a thread too short to be a line.

Because all the fibers are running

In one line, it seems a space, yet

It is not a thing in space. ”

From simple installations to complex print processes

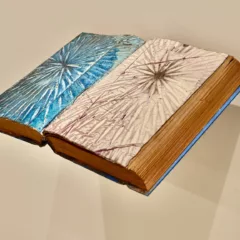

Two galleries on the first floor at 1222 Arch St. exhibit a broad range of Tuttle’s prints, books, and portfolios, which are complex investigations into the spacial layering–real and illusory–involved in the printing process. Does the ink sit on top of the paper support, or do they become one? When another layer is inserted on top of the supporting sheet–in a process known as “Chine colle”–where does it figure in the final work? A question made more complex when that layer is not the usual, absorbent Japanese or Chinese paper, but a nonabsorbent screen.

Unlike the intentionally casual construction of his wall and floor works, Tuttle’s prints are virtuosic explorations of printmaking techniques, achieved with support from a number of the best print workshops. He has used a complex range of processes, often combined in a single print, which are likely to be most appreciated by viewers with a serious knowledge of printmaking. They include: lithography, monoprinting, etching, aquatint, drypoint, letterpress, embossing, woodblock, wood engraving, screen printing, stenciling, inkjet printing, and hand-stamping. But any viewer willing to slow down and study the work should be able to appreciate the subtle and rich visual effects Tuttle achieves.