[Evan racks his brain for insight into a neuroscience-inspired show of works, finding himself a little lost in the neural network. — the Artblog editors]

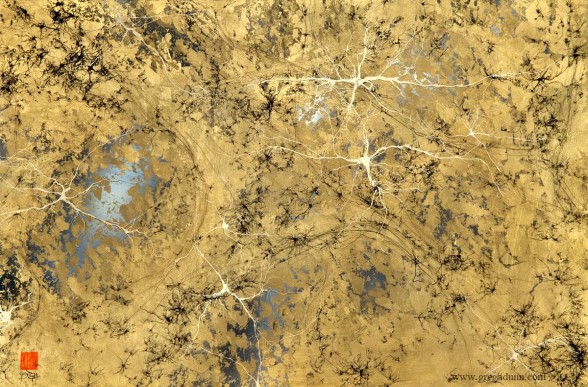

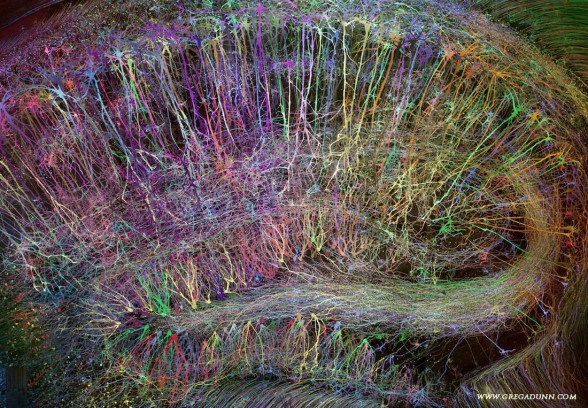

The hodgepodge of scientific imagery, Eastern-influenced design, and ultra-sleek presentation that artist and neuroscientist Greg Dunn presents in Mind Illuminated at the Mütter Museum can’t seem to decide what it wants to be–art, science, or spectacle. The product of an artist with an abundance of ideas about the human brain and art and the resources to see all of them through without restraint is jumbled. Intermittently, I found myself gripped by some of the more minute details. But I had to work for it.

Branching off

I imagine that scientists and doctors–those who have an intimate knowledge of the nature of neurological relationships and research–will have a very different reaction to the work than I did. Dunn’s work hangs mostly in medical departments of universities like Johns Hopkins and Carnegie Mellon. While the written material that accompanies the show explains Dunn’s inspirations in layman’s terms, a more intimate knowledge is still required to deeply access the work. At a certain point, I got a lot further by viewing the pieces as abstract visual experiments.

Restraint resonates most

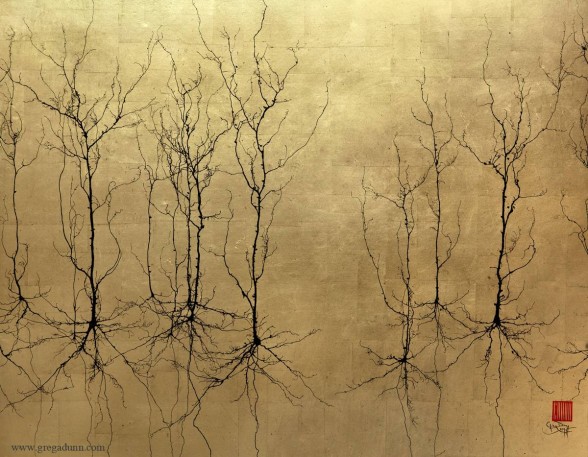

He is clearly influenced by Japanese and Chinese landscape works and scroll paintings, even utilizing a red-ink seal on his pieces as a signature. His substrate is mostly gold with the application of black ink.

Probably the most successful single component of Dunn’s work is his use of differing shades and applications of microetching that make certain lines appear or disappear as the viewer moves across the pieces. The single works in fact contain a multitude of separate experiential versions of themselves, meant to highlight the complex systems of communication and action/reaction that occur constantly within our brains.

The following scroll paintings are far more delicate than their metal and dark-wood surroundings, and they offer a welcome respite from the headiness of the preceding work. “Alzheimer’s Triangles” is particularly beautiful, incorporating subtle pink tones in the meandering black ink–a serenity that turns sour when the reality of Alzheimer’s sinks in. Dunn has made something so ugly and so destructive into a pseudo-representational and visually astute interpretation of reality.

For these reasons, I find the last work in the show to be the most moving. “Blaze in the Blacks” is an exercise in restraint in a sea of excess. Cloudy, seemingly brushed metal is canvas to many small silver dots, rippling out and fading into the ether of their surrounding. It is mesmerizing, rewarding the viewer with a more complete and less exhausting look at the functions of the body’s data center. Ending with this was a good decision.

As an artist and neuroscientist, Dunn situates himself downstream from the likes of Anna Atkins and John James Audubon, who long ago made work that was driven by research as well as aesthetics. If he incorporated more of the reasonable visual restraint that these artists did, he could do far more with far less.

Greg Dunn’s exhibition, Mind Illuminated, will be on display at the Mütter Museum from July – December 2015.

Evan Paul Laudenslager is an artist and writer currently living in Philadelphia. He is a graduate of Tyler School of Art.