[A.M. reviews a strong show of works linked by ties to scientific processes and the natural world. Though the show is over, its impact continues to move us! — the Artblog editors]

Natural Impulses was the poetic appellation for an exhibit of sculpture and paintings mounted at Locks Gallery this past May. Nature, science, culture, and craft were the underlying impetus behind the concept of the show, featuring works by Hilary Berseth, Nancy Graves, Maria Nepomuceno, and Alyson Shotz. Of significance were the different processes used to reconfigure or approximate natural forms. However, what resonated within the work on display was the hand of the artist.

It is fathomable that the artists, albeit in some instances with assistance, created the works themselves–a novelty in today’s art world, where readymade multiples of new or purchased objects and prefabrication dominate, and the artist’s involvement in construction is minimal or nearly nonexistent.

The diverse presentations of sculptures and installations overruled the impact of the two-dimensional works. However, the paintings by Alyson Shotz helped to anchor the space. In viewing this exhibit, I gravitated almost exclusively to the sculpture and installations.

Organic shapes and natural growth

In the center of the spacious upstairs room of the gallery was “Still Life” (2014) by Alyson Shotz, an installation with leafy formations at the top, designed to imply genetic modification. Whimsical in appearance, the piece is reminiscent of handmade toys found in the Caribbean. This sculptural work is made, in part, of rubber stretched over wire, but the leaves of the work belie their construction. Red plastic tubes attach simulated bamboo-like stalks to each other.

A nice touch in “Still Life”–possibly a precursor to Shotz’s explorations of light–are the puddles of cut mirrors at the base of each cluster of stalks. Over the years, Shotz has traversed many styles; attenuated threads connect her sculptures/installations, which are like lyrical drawings in space, to her paintings of organic orbs and shapes and to her light-inspired works.

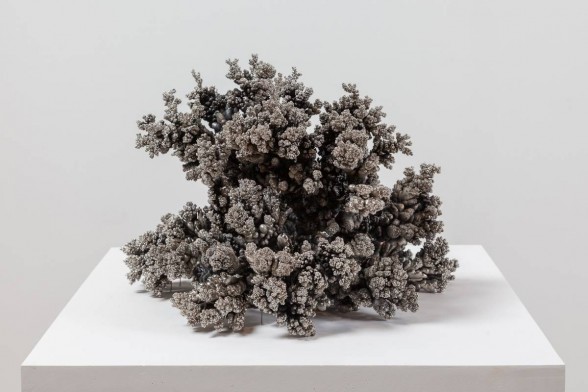

On the periphery of the space were installations of various sizes and levels of engagement. Hilary Berseth’s honeycomb sculpture, “Programmed Hive II” (2014), is organic and intriguing, as are his crystallized works made of electroplated copper and nickel. These works require multiple phases of manipulation and careful monitoring. Berseth starts with copper, and as the work grows, nickel is added, producing silvery filaments with oxidized copper markings. “Plated Point 2” (2010) resembles an elaborate breastplate, or, as the press release states, an aerial view of mountainous formations. “Plated Point 5” (2014) is a spiky mound that immediately brings to mind a coral reef; both works shimmer and dazzle in their intricacy. The intrigue of the works not only resides in their ultimate forms, but in how they were created: Berseth’s work is built around controlling and reconstituting natural materials.

Subtle feminist messages

(289.89 x 240.03 x 200.03 cm). Photo courtesy of Locks Gallery.

Brazilian artist Maria Nepomuceno created a serpentine installation in the corner of the gallery that crawled up the walls and extended across space, anchored by circular blue beaded mats strategically placed on the wall and floor. The mats loosely infer placentas with umbilical cords attached. At first glance, these woven beadworks appear to be macramé or made from another type of material. There is an earthenware urn and a bowl included in the installation as well. “Untitled” (2014) is a cross between a partially constructed room or intimate space and a symbolic abstract structure.

A viewer might assess that the innocuous modernistic chair at the center of the piece is a little out of place; should the artist have chosen a design type that more closely related to the overall concept of the installation? The chair, in its pivotal location, seats a blue beaded pod that cradles several small gourds. The use of beads, gourds, urns, and the process of weaving are cultural references particular to “women’s work”. The capriciousness and severity of the implied forms in this untitled piece coexist and serve as counterbalances.

(31.12 x 33.66 x 36.2 cm). Photo courtesy of Locks Gallery.

If familiar with Nancy Graves’ paintings and public works, the viewer may be caught a little off-guard by the intimacy of the two pedestal works on display. Of note is “Wax Works VI” (1987), which incorporates elements that resemble a jawbone of a lamb and vertebrae of an unknown creature, along with a mixture of metal and unidentifiable materials. Cast in bronze, the sculpture’s baked enamel of bluish hues, aqua, azure, and cobalt, contrasts with the other Graves sculptures on display, which are coated with layers of polychrome paint. Notably, Graves studied the lost wax method to create this series. As an artist who worked in a multiplicity of disciplines, she never followed a unified approach, but constructed distinct bodies of work that reflected diverse interpretations of her interest in archeology, the natural sciences, and cartography.

Overall, the installation of the works by these four artists was delightful and even powerful. The science and nature premise was a clever point of reference; perhaps what was most satisfying was the strength of individual pieces and how they worked together as a whole. The works dialogued with each other, creating a suite akin to a classical quartet.

Natural Impulses ended May 23, 2015 at Locks Gallery.