New books from vaunted artists

Post-war Japanese photography has enjoyed a reputation for being provocative and alien to the Western eye, a boiling concoction of a reeling political environment and shifting cultural landscapes. The photographers born of the sometimes repressive and often confrontational years following the Japanese defeat in World War II formed a vibrant and expansive art scene of their own. Inspired more by the squalor and mess of unseen alleys than the cleanliness of the gallery wall, their art was not just a means of expression, but a means of coping.

A medium of particular importance to these artists was the photo book, an artist-designed volume to showcase photographs, often with less emphasis on the written word. More portable and visceral than a framed print, a photo book allows for an almost unlimited range of experimental design and content. Traces of traditional Japanese aesthetics are apparent even in the most daring artists’ work, but the influence of Western photographers did not escape them either–for example, Daido Moriyama, whose exposure to American street photographers of the same era influenced his grainy and active aesthetic.

Artists like Nobuyoshi Araki and Kikuji Kawada were leading figures of the medium in post-war Japan and continue to be to this day. Both photographers have recently published books. Kiwada’s The Last Cosmology is an exploration, through imagery of the sky and cosmos, of the changing heart and culture of a man “in the twilight of his life”. Araki, on the other hand, is the artist’s curated collection of his ouevre from dozens of portfolios made throughout his long career.

The edge of eroticism

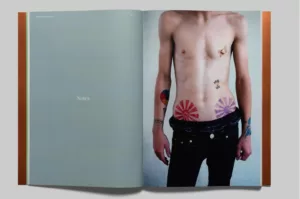

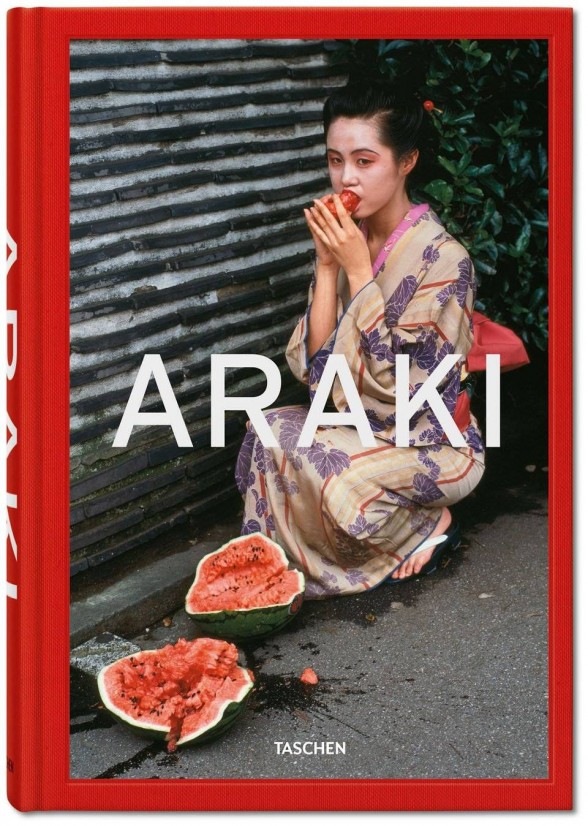

It is difficult to describe in words the raucous and crude personality behind Araki’s pictures. To say that his work is sexually charged would be an understatement; it is in fact an exercise in provocation. Born in 1940, Araki made images of sex culture in Tokyo in the 20th century–both in his private relationships and in brothels, clubs, and the streets of the city. In the book, the artist has placed these sensual pictures alongside images of delicate flowers, street scenes, food, and most famously, the Japanese art of kinbaku, or bondage.

His work, peppered with erotic scenes, toes the line of being exploitative and empowering, and I am never quite sure on which side of this line I find my opinion. In an active attempt to combat the thick cloud of censorship surrounding so much related to sexuality in Japanese art, culture, and law, Araki’s images are, if nothing else, a cry for freedom.

The book itself is as flashy as the photographs it contains. With 568 pages of photographs and a bright red cloth cover, the volume is a retrospective handpicked by the artist himself. Everything about it should be overwhelming, but it somehow manages to deliver moving narratives of beauty and freedom buried in a grey and shrouded reality. Interestingly, this 2015 edition is a republishing (featuring some new images) of the original 2003 book, brought back because of high demand and high price tags for original copies. It certainly isn’t the kind of book to keep on your coffee table when your parents come to town. But hidden in your bookshelf and explored on a whim, it is a powerful antidote to complacency.

Space to think

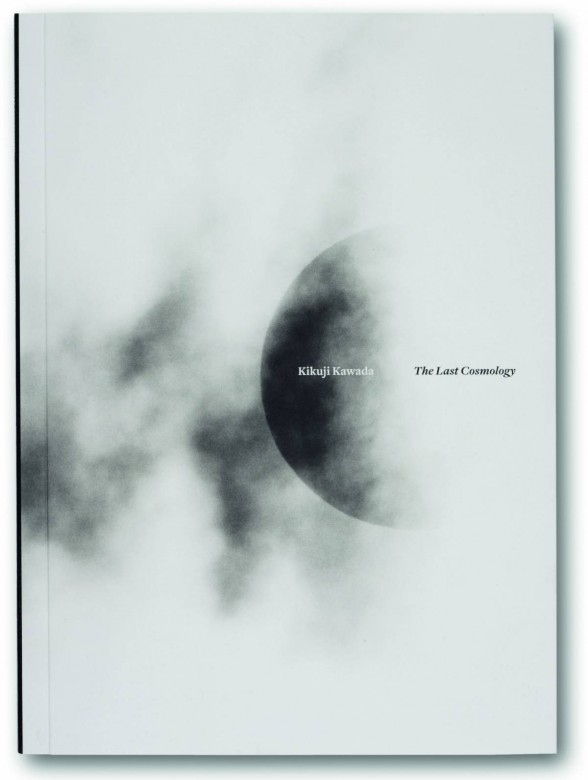

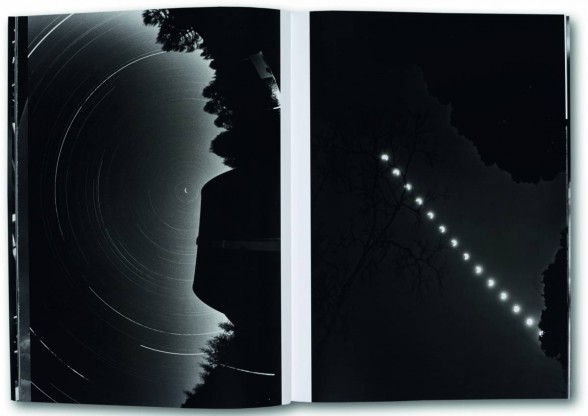

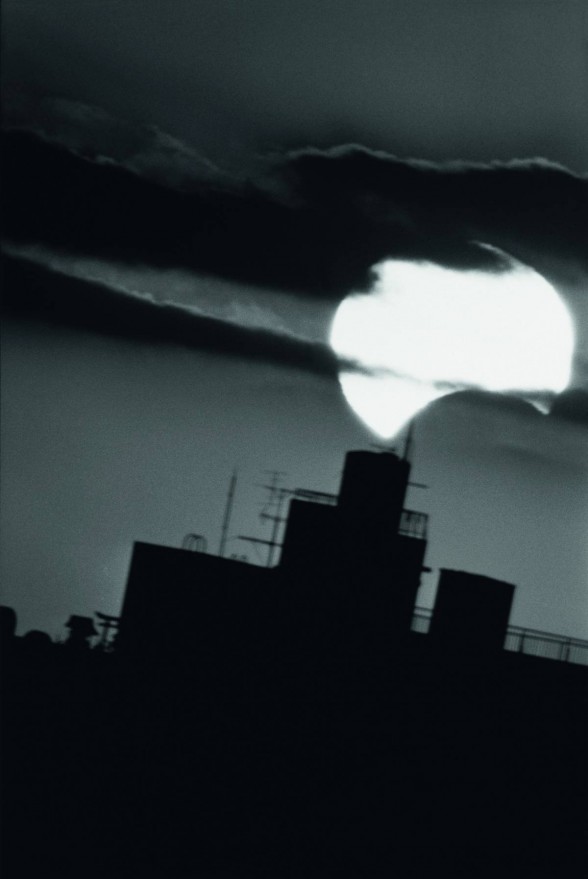

On the complete opposite end of the spectrum, you’ll find Kikuji Kawada’s The Last Cosmology. The aging photographer (born in 1933) imbues this book of photographs made from 1980-2000 with a palpable sense of an impending void. Kawada grew up in the years following the war in an era of reconstruction, deeply rattled by his boyhood stasis and thrown into a very real and very imminent identity crisis. His 1965 book Chizu (The Map) has been called the greatest Japanese photo book ever made.

His photographs seem nostalgic for a reality that never quite came to fruition. Relying heavily on imagery of stars, eclipses, and solar flares in relation to symbolism from the Showa Era in which he was born, the black-and-white photographs are deeply emotional and inextricably tied to an awareness of death.

Not all of the images are of the sky, however. Grassy lawns and pebbled asphalt lend their textures alongside the softer impressions of clouds and rainstorms, and eventually, the differentiation doesn’t seem to matter anyway. Each frame displays a fragment of the physical world affected by its ephemeral passersby. In this meditation, history is indiscernible from myth.

The book is published by MACK, consistent producers of well-made photo books. Images bleed off the pages and into one another in a way that keeps pages turning and eyes fixated on intricate details found in the grain of Kawada’s film.

Although the books and their content may fall on either end of the visual spectrum, they represent a snippet of why photography in Japan merits all the more attention from Western eyes. These two aesthetics come in two very different forms, one a career-spanning retrospective and one a newly published work. Although the photographers are only seven years apart (Kawada is 82 and Araki 75), I wonder how much this shaped their perspectives. Kawada would have been 12 in 1945, when Hiroshima and Nagasaki were bombed, while Araki would have been only 5, not aware on the same level. They offer two very different types of coping–one expressive and outstretched, the other deeply introspective.

The Last Cosmology by Kikuji Kawada: 86 pages, 67 tritone plates, 24 cm x 32 cm, double-sided cover, each with a gatefold. $75, published by MACK.

Publication date: April 2015

Araki by Nobuyoshi Araki: 568 pages, hardcover, 9.2″ x 13.4″. $69.99, published by TASCHEN.

Original publication: 2003, republished 2015.

Evan Paul Laudenslager is an artist and writer based in Philadelphia. He is a graduate of Tyler School of Art.