First I thought it was the figure of a young man riding a bicycle. He seemed to be straddling what I thought was a bike and leaning forward with hands on the handlebars. Then I realized that it was the spitting torture.

I’m not sure how I learned about the spitting torture–probably the hard way. I have always thought of it as one of those harmless varieties of roughhousing imposed upon wriggling children. For those of you who are not familiar with it, the child is pinned down and straddled, and a string of saliva is dripped out of the torturer’s mouth, aimed at the face of the screeching child, and sucked back in before gravity takes over. Unfortunately, of course, there are rare occasions upon which one goes too far and, with regret, the victim actually gets spit on.

Irrespective of the potential disgustingness of this version of the spitting torture, I learned, after visiting this exhibition, that there is a whole world of pornographic spitting out there in which masochistic subjects, usually men, are humiliated as their naked bodies are drenched by the saliva of a group of women. Go figure.

Weird and wonderful

In Schutz’s piece, “Spit,” which focuses upon the torturer/spitter, there is no emotion, and this lack of mood is reinforced by the uniformity and angularity of the composition. There is no indication that the spitter has attempted to spare the victim, and there is no reaction registered by the victim. You find this sense of dissociation in a number of the other pieces displayed in the exhibition, and it can be disturbing. Even when a Schutz figure is far more expressive, as many of them are, they are often portrayed as primitive forms, even caricatures, and they can convey an eerie sense of dissociation from their environments.

“Spit” is one of the smaller, and perhaps minor, pieces in this solo exhibition of 29 of Schutz’s works. But for me, this charcoal drawing was one of the most striking pieces in the exhibition, and it is, I think, emblematic in many ways of all the work presented.

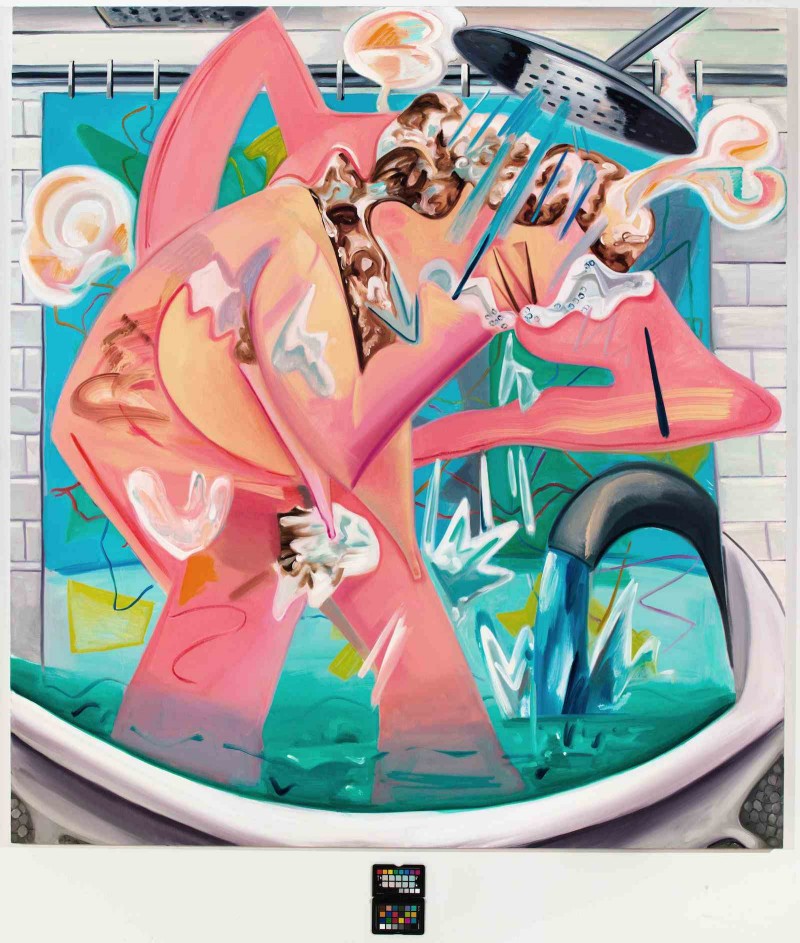

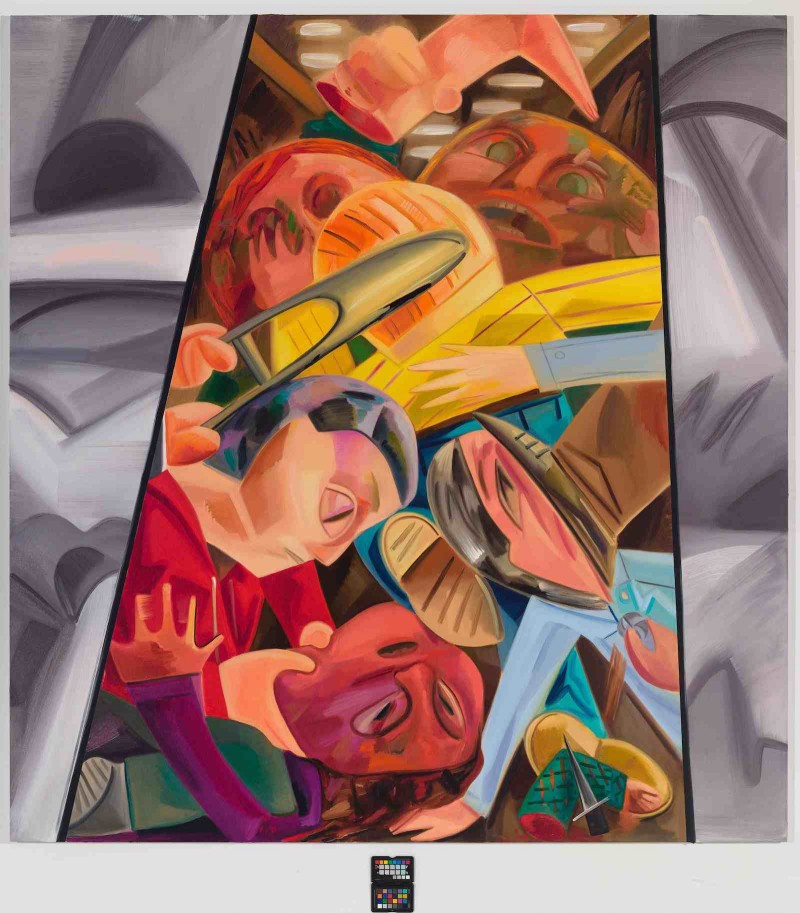

In any event, I venture to suggest that this is the first time the subject has appeared in a work of non-pornographic art. And this wonderful, offbeat subject matter uniqueness is typical of Schutz’s work and distinguishes her as an artist and as a thinker. In Schultz’s work, you find modern life portrayed through a discombobulating brawl in an elevator (perhaps take-offs on the tales of Jay-Z and Beyoncé’s sister, Solange, and Ray Rice and Janay Palmer); a lion eating its tamer; a sleepwalker; a slow-motion shower (in which there are no boundaries: everything, including the bather, is fluid); a stoned and freaked-out driver at a police stop; a strange, colorful Yoda-like figure with large, hanging eggplant testicles, carrying a basketball.

One of Schutz’s huge and very busy paintings, the overall effect of which lives up to its name–“Assembling an Octopus”–portrays what appears to be a life drawing class superimposed upon a beach scene that includes a forlorn young man peering between the legs of the bottom half of the nude woman lying on her back in front of him. In a sense, that is how I felt at the exhibition.

Compression obsession

There are 12 paintings in the show, and for the most part, they are large, some very large (one of them is 9.5 feet by 17 feet), and action-packed, sometimes bewilderingly so. Schutz is obsessed with compression–even her large pieces often involve what she has described as “high action in a compressed space”–which can be at once magnificent and overwhelming. Indeed, fathoming the scope of some of these pieces becomes slightly too labor-intensive for my taste and puzzling, even dumbfounding.

About Schutz

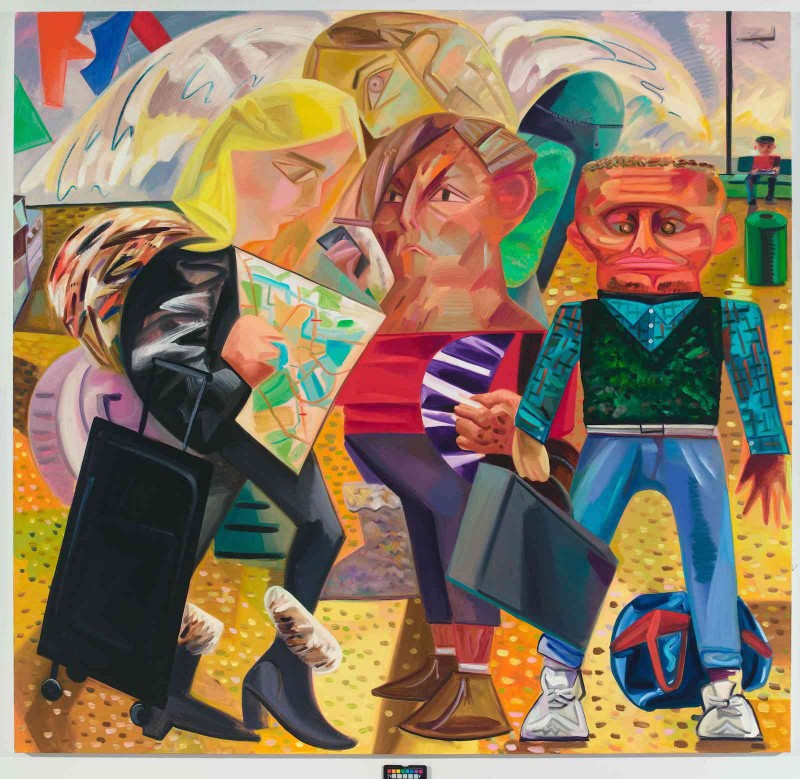

Schutz’s “Swiss Family Traveling” is approximately 7 feet square, and I think an interesting example of her work. Note the fabulous color scheme, the odd, but perfect expressiveness of the figures and the compression of space. Schutz brilliantly captures this scene with a masterful simplicity that contrasts sharply with the Penn Station-at-rush-hour complexity you find in a number of her other paintings.

I have heard Dana Schutz’s work compared to that of the Austrian artist Maria Lassnig. I have heard her speak about the influence of German Expressionism upon her, and about her admiration for many contemporary artists, including the Latvian Ella Kruglyanskaya. But Schutz’s work is so unique and idiosyncratic that one is hard-pressed to pinpoint her artistic lineage. Let us say that while she clearly has absorbed a great deal from her ancestors, she succeeds in turning much of what we find in contemporary art on its head, and her extraordinary perspective is exhilarating.

Some of my best writing occurs when I don’t know where it is going to take me. When the story takes over. And I suspect there is an element of that in Schutz’s work, because there are so many surprises along the way; there is so much unrestrained inventiveness, humor, and violence, and an amazingly rich, nuanced portrayal of the vagaries of modern life.

Dana Schutz was born in 1976 and raised in Michigan. She received her MFA from Columbia in 2002 and lives with her young child and husband, the sculptor Ryan Johnson, in Brooklyn. This is her second solo show at Petzel, the beautiful, but somewhat intimidating Chelsea gallery. Schutz’s work, of course, has been exhibited extensively, has been highly acclaimed, and it appears in numerous museum collections, both nationally and internationally.

DANA SCHUTZ: Fight in an Elevator is open through Oct. 24, 2015 at Petzel Gallery, 456 W 18th St., New York, NY.