Take Two‘s treasures

A Monet-like photograph of water lilies fading in water (Stephen Shore), a monstrous face drawn over a dark backdrop (William E. Parker), and printed leaf-cutouts installed in conversation with images of birds on the exhibition walls (Eileen Neff)–all these photographs might seem disconnected on first impression, but this would be deceptive. The images in the current exhibition Take Two: Contemporary Photographs at the Philadelphia Museum of Art present a wide range of conceptual and technical approaches in photography today. Peter Barberie, Brodsky Curator of Photographs, arranges photographs from the last 50 years. His selection from the collection extends the series’ first counterpart, Take One (see my previous review) through an ambitious range of digital and analog items, documentary images, staged interventions, and sensual representations. Besides questioning the impact of photography on modern societies today, Take Two strongly imparts a historical debate on photography as a medium of art.

Take Two includes the works of 20 internationally renowned artists and is mostly organized in series of objects, human bodies, places, landscapes, and nature scenes. The presentation’s art-historical implications and categorizations might be overwhelming to the casual museum visitor who is confronted with genres from landscapes to portraits and methods from serial documentation to mise-en-scène in photography. Also, the repetition of many of the same artists from the first exhibition, Take One, can feel redundant. However, the show is nonetheless a precious tidbit for anyone who wants to experience a high-quality exhibition, featuring the treasures of the photographic collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. For a first insight, let me point out some highlights from An-My Lê, D.W. Mellor, Les Levine, and Paul Cava.

Roles of pictures

The exhibition emphasizes the role of photography in addressing social and historical changes in modern societies today, as exemplified by the black-and-white photograph “Untitled, Mekong Delta” (1994) by An-My Lê. In a long exposure, a family is posing with their geese along a small stream; the static landscape and their owners are contrasted in the blurry movements of trees and animals around them. As part of the series project Viêt Nam, the photograph was taken during the artist’s return to Vietnam in her mid-30s. Now a professor in the U.S., An-My Lê was born in Saigon and left the country as a teenager with her family in 1975. Shifting between historical and photographic times, the work is a silent reminder of the Vietnam War 40 years ago. In the context of her personal experience, the image also raises questions about the ethical discourse and politics of migration and refugees in our global world today. Confronting the current debates in Europe, this ambiguous image of a rural landscape tactfully examines violent memories and interweaves them with a contemporary visualization of war and recovery.

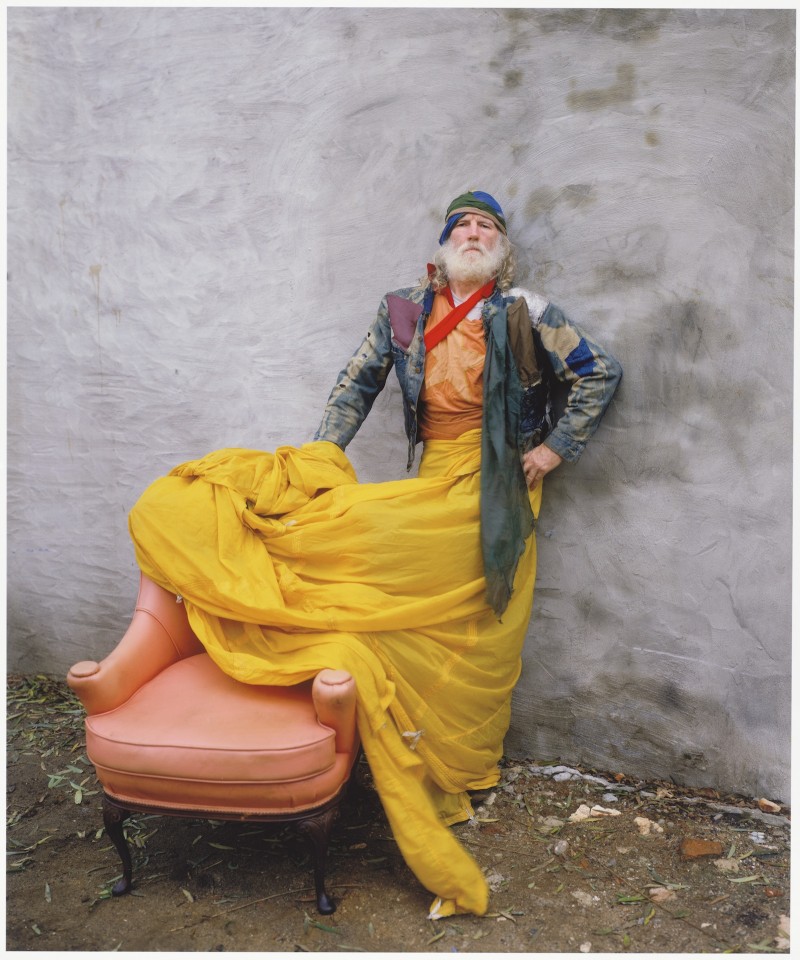

Documenting the personal changes of a Philadelphia citizen over three decades, D.W. Mellor’s series of photographs of Tom Garvey–one-time stranger, now the artist’s friend and muse–is also an examination of society’s impact on personal identity. Garvey mimes a proud Harley-Davidson biker in ”Mirrors” (1976), stages an ancient Roman imperator in “Noble” (1982), and embodies an iconic nude sculpture in “Garvey” (1994). Through his photographic lens, Mellor follows Garvey’s almost childish protest against the monotony of life. In an accompanying letter by Tom Garvey inquiring about the cheapest real estate in Pennsylvania, the photographic display develops an absurdity that unfolds, layer by layer, our social desires and personal qualms.

Techniques of pictures

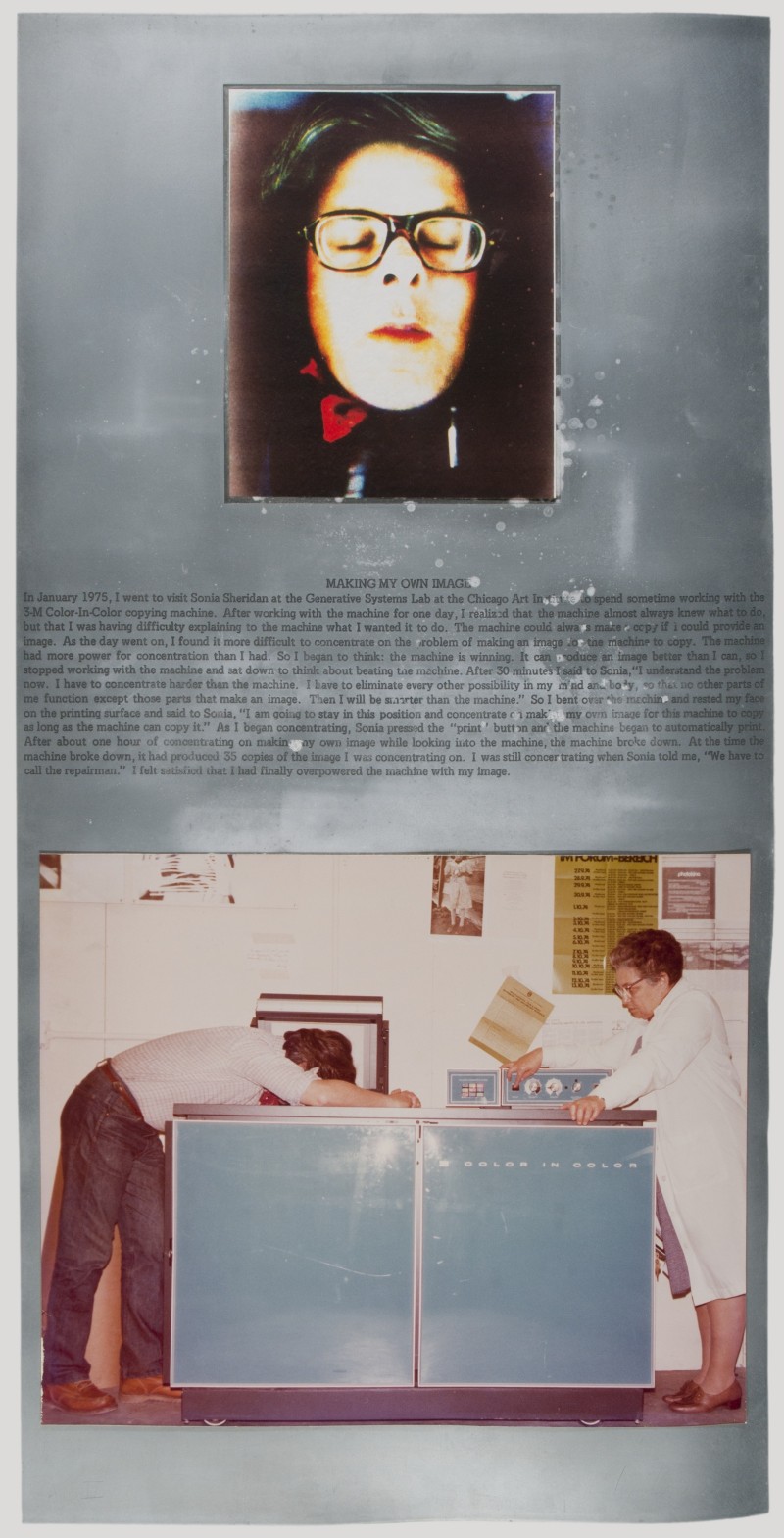

Les Levine’s assemblage “Making My Own Image” (1975) is a combined zinc plate with engraved text and a color photocopy developed at the Art Institute of Chicago. Thinking about how to produce an image with this then-new photocopy technology, Levine fought a quintessential modern battle of man against machine by copying his own face until the machine broke down. His manic game reminds one of the legend of the steel driver, John Henry, who fought an uneven race against a steam-powered hammer, winning the competition, but dying on the railroads immediately after. However, Les Levine’s destructive depiction of his self does more. In fact, it questions the role of new technologies in photography while at the same time regenerating the significance of the artist.

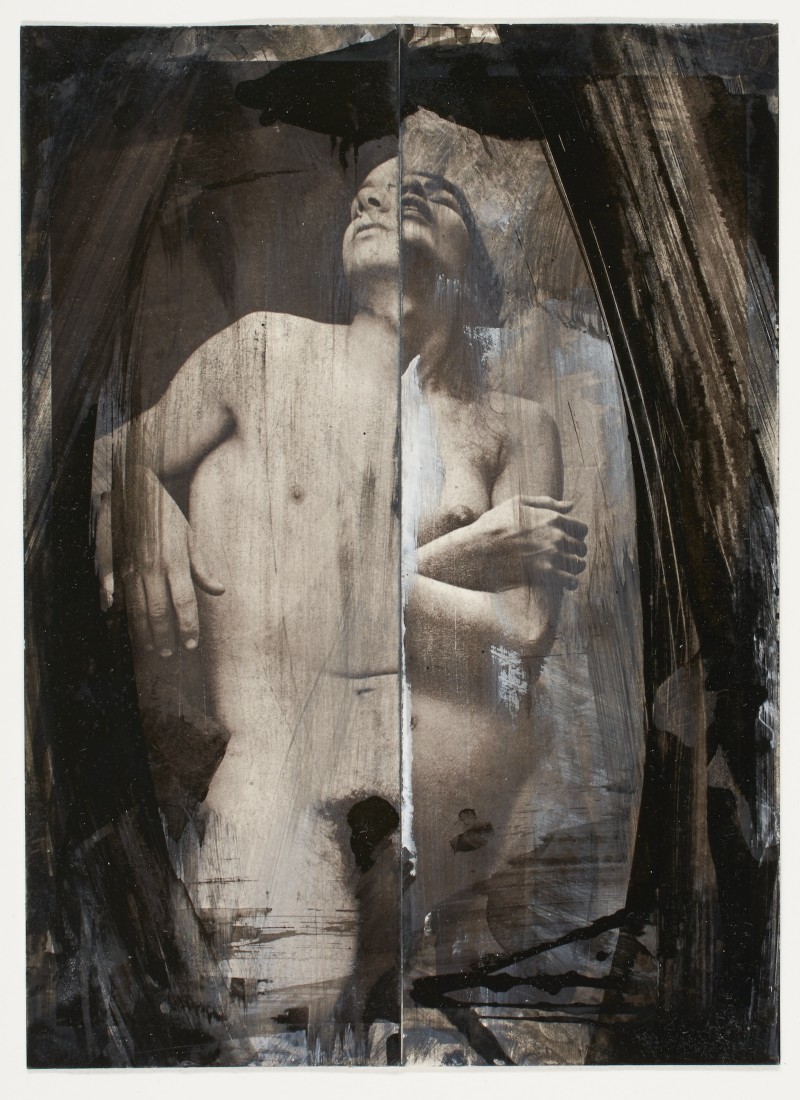

This relationship between technical developments and the photographer inevitably refers to an art-historical debate led by Walter Benjamin’s insight about the disappearance of the aura in an art work through mechanical reproductions. Paul Cava’s photographs respond to Benjamin’s statement as well. The American photographer and art dealer develops the act of “overpainting”. As in “Man/Woman” (1997), part of a series of four collages of the same two photo-offset lithographs, Cava manually inscribes artistic authorship onto photographic images. The work presents two humans each in a portrait and a combined half-cut, overpainted with ink. In the sense of accentuation and correction, Paul Cava edits the photographic template and condenses as well as alienates the body’s physical expressions–an inter-media gesture that balances humans struggling with identity and social representation.

Even though Take Two doesn’t assert a claim of completeness–digital photographs on the border of abstraction or electronic art actually are missing–the exhibition adds a deep view of the technical extensions of the medium of photography and its diverse contexts and representations today. Besides the works mentioned above, the show includes wonderful photographs by the following artists: Robert Adams, Dawoud Bey, William Christenberry, Patrick Faigenbaum, David Goldblatt, Ditta Baron Hoeber, Henry Horenstein, Zhang Huan, Nicholas Nixon, Robert Rauschenberg, Gerhard Richter, Walter Rosenblum, and Cindy Sherman.

Take Two: Contemporary Photographs is on view through Nov. 15, 2015 at Julien Levy Gallery in the Perelman Building at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from Tuesday to Sunday, 10 am to 5 pm.