Cavin Jones’s recent exhibit Saying Something, at House Gallery in Kensington, varies somewhat from the recent mural works he is known for.

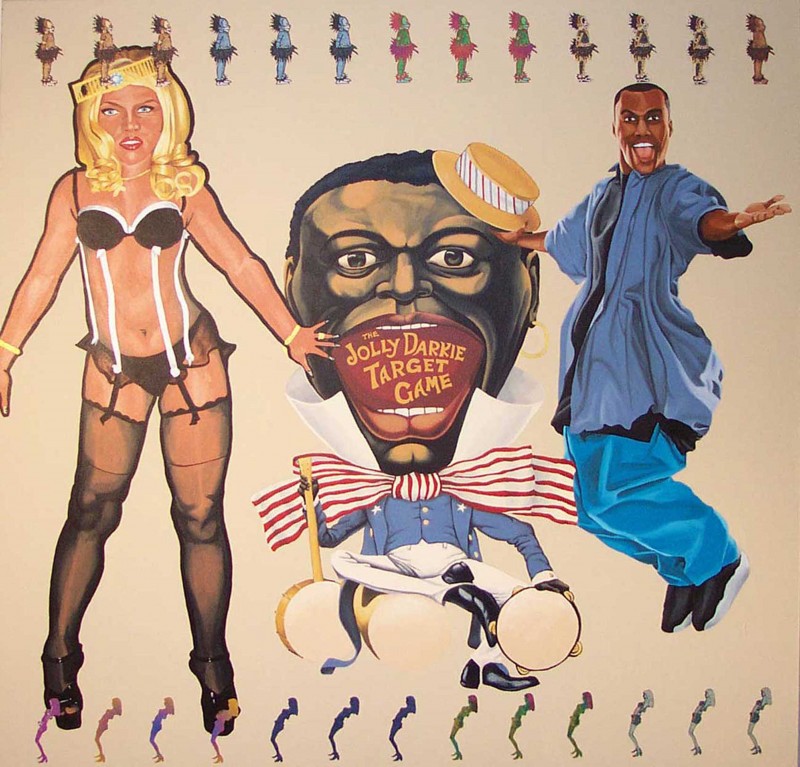

In Saying Something, Jones presents four paintings and four works on paper, which are in fact studies for larger works. The exhibit includes personal work generated between the late 1990s and 2015. Of note is his attempt to subvert or “flip the script” on black stereotypes. The painting “Check Out the Real Situation” features a surgically altered Lil’ Kim in a bustier complete with black garters and fishnets and blonde hair. The infamous rap artist Kim here is emblematic of some black women who, in attempting to approximate a white standard of beauty, will go to extreme measures.

All-American apparitions

These extreme beauty alterations are is not only true of black women, but Asians, Latinas, and whites, and women of a certain age, who frequently go under the knife to attain what is considered by the media and Hollywood as classic beauty. In all of America’s rugged individualism lies a desire, particularly among women, to conform to illusive standards of appearance.

Flanking Lil’ Kim on the opposite side of the painting is an Arsenio Hall-like figure caught in a mid-air leap with a buffoonish visage and arms extended, palms face-up. Placed dead-center is a laughing minstrel-like head with exaggerated lips, popping eyes, and a bellhop hat. This token of black memorabilia from the turn of the 20th century is a rendition of the target in a Milton Bradley game, The Jolly Darkie Target Game; these elements are set against a stark cream background.

Most of Jones’ titles are taken from American songs. His intent is to stress the American aspect of his work: what has happened here and has been made here. The paintings from this era are charged with sociopolitical content, from equating the lives of blacks to those of endangered species, to renditions of Mao and Huey Newton in the same frame in “Say You Want a Revolution (Well You Know…),” and to the parody of black entertainers. His sociopolitical content is apparent; there is no mistaking his intent in many of his large-scale paintings. In each work, the color scheme and emblems are carefully chosen to advance his content.

Subversion and questions of identity

The title of “Check Out the Real Situation” is taken from a song by Bob Marley. It has didactic overtones and parallels, on some levels, the work of Michael Ray Charles and the white South African artist, Anton Kannemeyer. While Charles and Kannemeyer intend to employ irony to make statements about racial stereotypes, their works court controversy, and the satirical reading message of their works tends in some instances to miss the mark.

After seeing Anton Kannemeyer’s piece “Pappa and the Black Hands” in the September 2009 ArtReview, I wrote to the editors.

“Kannemeyer borrows his imagery for “Pappa and the Black Hand” from the racist cartoon of Hergé in Tintin in the Congo. As you know the work of the cartoonist Hergé has come under fire recently. I think that artists who are not of color have a very different take on using stereotypical colonial imagery and may not be as sensitive to black audiences as they should be. Even though Anton’s work is allegedly satirical, the commentary is lost and the viewer is left scratching his/her head.

[Kannemeyer’s] work definitely needs text to explain the artist’s intent; therefore is it in fact effective? Just raising questions that come to mind. I showed the cartoon including the statement by Paul Gravett to my colleagues, who are black, and they still found the work racist.”

(The cartoon is a horrific tale in which Pappa hunts the black natives of the Congo and in shooting the native, which he mistakenly thinks is the same person, discovers he has murdered innumerable subjects. He then promptly cuts off their hands. This last phase of the comic alludes to King Leopold II’s rule over the Congo from 1885-1908, in which mass murder and mutilation, often the severing of hands and feet, was used to exert control over the native population as punishment for not meeting quotas in harvesting ivory and rubber, refusing to work, or staging revolts. It is estimated that during this period of genocide more than 10 million were slaughtered.)

While Kannemeyer’s work alludes to colonial atrocities, Jones’ painting evokes psychological spaces and metaphysical discourse on race. Whether Jones’ work makes the cut in successfully subverting black stereotypes is left for the audience to decide. Jones’ references to entertainers, like Lil’ Kim and Arsenio Hall, are caricatures that imply problems of identity. His site of critique is for white and black audiences to reconsider the present-day Hollywood/mainstream imaging of blacks, as addressed in the Spike Lee movie “Bamboozle,” juxtaposed against the earlier portrayals of minstrelsy.

Size and space show power

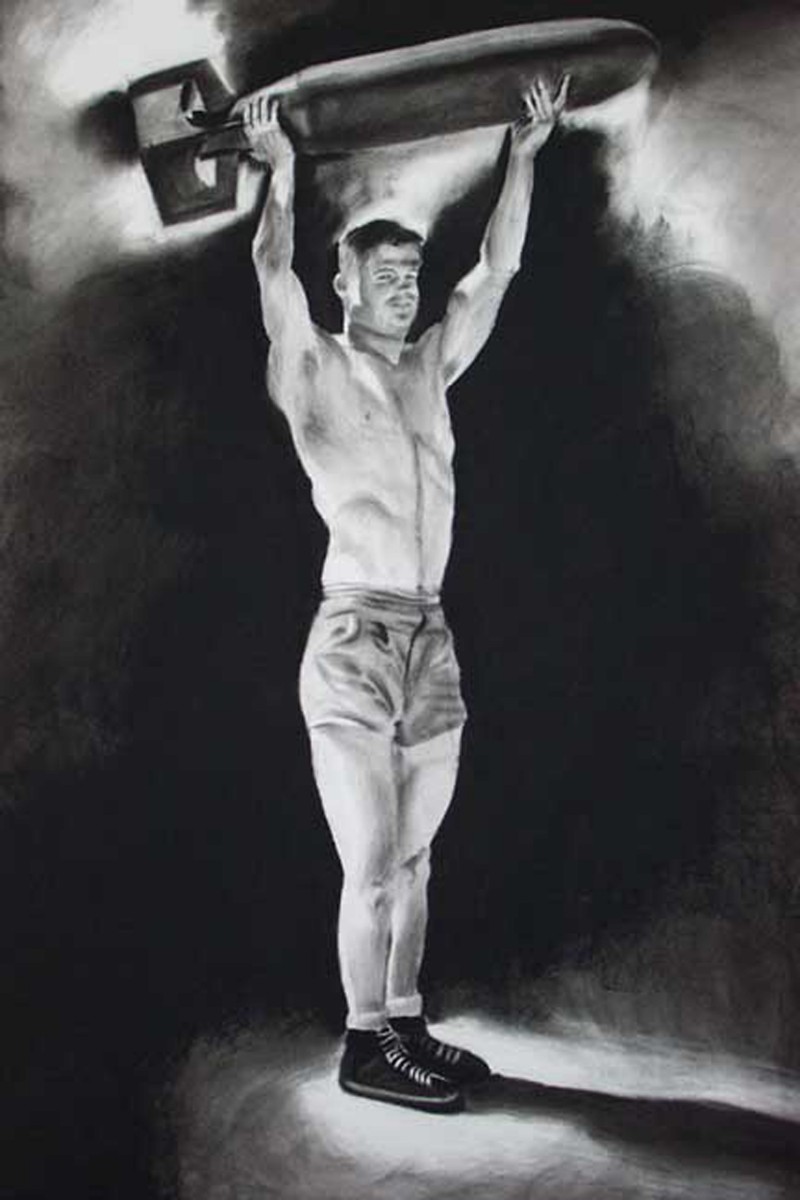

The modulation of the figures in Jones’ presentation is most successful in his drawings of an F-16 airplane and a 1950s Korean War-era propaganda image of an army figure in shorts holding a bombshell. In these works, the proportions are convincing, in contrast to his paintings, in which some of the figures are jammed into spaces that appear to be too small. However, Jones’ five-window compositional device in “To See Through Eyes That Only See What’s Real,” while symbolic, holds the painting together well. Actually, the size of things designates prominence, creating an in-and-out effect and an overall tension.

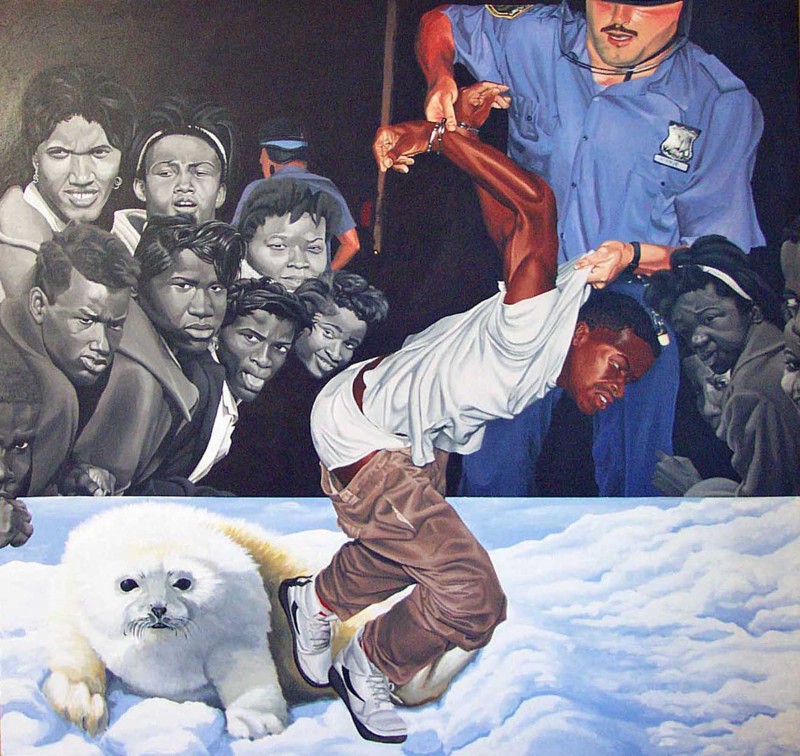

What is key in “To See Through Eyes That Only See What’s Real “ is the subject matter. (The title of the work is taken from the Elton John song “Grey’s Field” on his Good Bye Yellow Brick Road album.) A policeman flashing a baton grabs a youth, whose pants are drooping way below his waistline, by the collar. This scene has become all too familiar in recent times and evokes a long history of assassination of the black male from lynchings to present-day murders at the hands of the police.

By making the youth somewhat diminutive, while the policeman looms large and only partially visible on the right-hand side of the canvas, Jones evinces power relationships and reiterates his use of dramatic tropes pertaining to spatial relations. On the upper left-hand side of the painting is a portrait of a tight huddle of youth rendered in hues of grey. Below is a painting of a baby seal, an endangered species. Jones juxtaposes the relationship of animals with black youth, making the analogy that America places more emphasis on the preservation of animals than on human life.

Jones’s background is strongly steeped in the traditions of murals; from 1995-2007, he worked for the Philadelphia Mural Arts Program and received the Independence Foundation Fellowship in 2001 to study Roman frescoes and Renaissance tempera and oil painting in Italy. Since 2008, the artist has created 475 portraits commissioned by Walter Palmer, social justice professor emeritus, for the Walter Palmer Leadership and Learning Partners Charter School (see portraits here). Although the school is now closed, Jones’ herculean act will be long remembered. He spent approximately seven years of his life creating these works.

The House Gallery, run by Michelle Marcuse and Henry Bermudez, is a small home gallery that revels in the opportunity to present emerging artists and some of substantial stature within the Philadelphia arts community.

Cavin Jones‘ Saying Something ran from July 1 – Aug. 20, 2015, at HOUSE Gallery.