For many middle-upper-class people who experienced (or have relatives who experienced) the booming financial glory and suburban development of post-WWII USA, Becky Suss’ paintings may look just like home. Or, for anyone in love with mid-century modern design, they may look like your dream home.

Reviving lost spaces

Suss’ paintings are large like murals or stage sets. They are big enough to “re-establish the room as the room in the painting,” the artist told us at the opening gallery talk. As such, the ICA gallery becomes the living room, bedroom, entryway, and dining room of the artist’s grandparents’ Long Island suburban home (now demolished), or her great aunt and uncle’s Philadelphia apartment. These are the familial domestic spaces in which Suss spent time while growing up. She paints these interiors with such exacting detail that we get the sense she knew intimately every texture and pattern therein and is communicating this intimate knowledge to us.

For example, Suss paints a silk lampshade in ways that elucidate each silk fiber; her wood floors show every intricacy of the grain. This specificity is convincing and visually seductive. And although it seems to be out of fashion to employ classic visual analysis and description, there are no works which demand this method more than Suss’. Take a close look: these paintings form a visual inventory of every object, surface, or material. These are paintings about the surface of a painting. Palm-leaf bedspreads, winter branches outside a picture window, and woven floor rugs form large areas of flat patterning. Suggestions of orthogonal lines are negated by brightly lit interiors, unmodulated paint, and skewed viewpoints. The rectangular shapes of the canvases are consistently echoed by the rectangles of the depicted mirrors, doorways, windows, sofas, and tables. These paintings are designed as skillfully as the David Gil Trigger mugs and Danish Modern mid-century dining set that we see in these painted domestic scenes.

Yet despite the surface finesse and lucid detail, much remains unseen and mysterious. Could these highly articulated surfaces be red herrings distracting us from murkier aspects of meaning? Take the painting “Bedroom (Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám)” (2015), for example. In it we see a bed painted so as to communicate clearly the specifically patterned, white and lavender chenille bedspread. Considering it again, we see this bed as a hard, flat, rectangular shape jailed between two black iron stanchions; no body can actually rest here, and none would want to. Likewise, as viewers, our eyes can’t rest or enter anywhere in this painting. They bounce across the surface from detail to detail, shape to shape, only to get caught in the false promise of a mirror, in hazardous and vertiginous viewpoints, or in large areas of flat, palm-leaf patterning that catches us like a net. There are no shadows in these brightly lit interiors, there’s an airless quality. In short, there’s something uncanny here. For, although these paintings may look just like home, this is not necessarily a hospitable place.

The artist described this body of work as the result of “working backwards,” piecing together an interior room around an initial investigation of a known object from that room. For “Bedroom (Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám)”, she “started with a lamp” that belonged to her mother and went from there. In this painting we also see a book of poems that “fascinated Suss as a child,” as curator Kate Kraczon writes in the gallery notes. Soon, as Suss described, “There is a space, and it can say everything but it is also very limiting at the same time.”

Clues and class

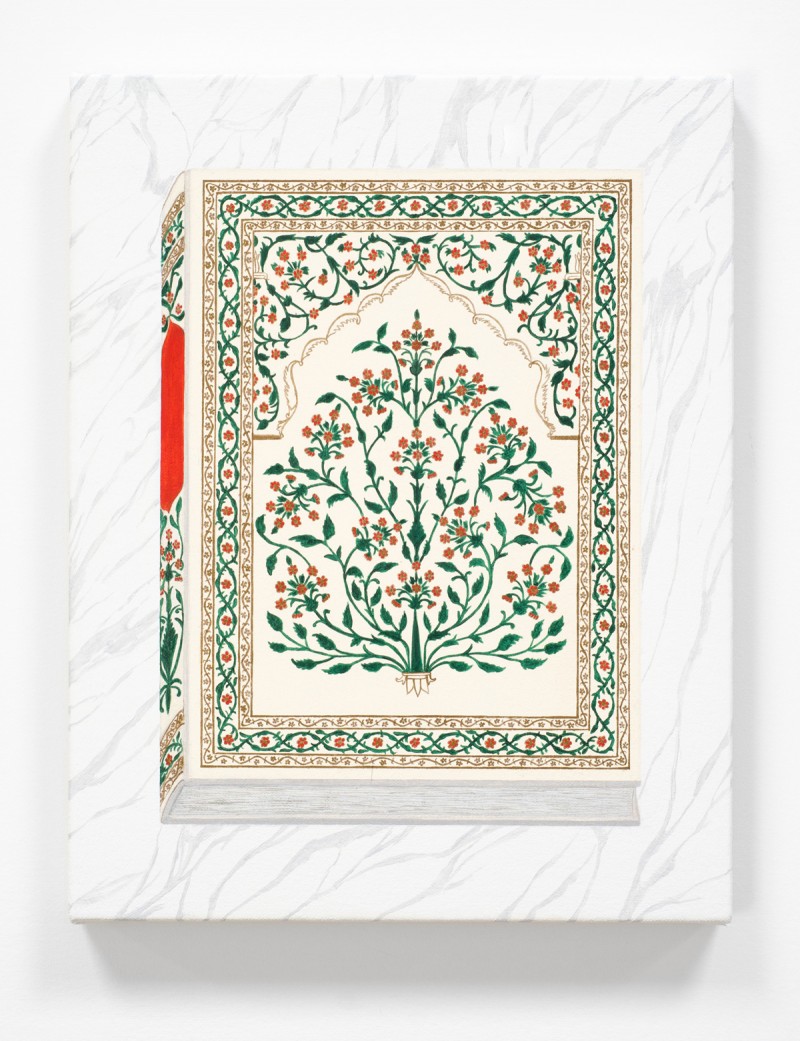

Suss said that the lamps and books can be “clues” to meaning and that with these paintings she is “revisiting and reinventing, figuring out what the objects mean.” That book of poems in “Bedroom (Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám)” is presumably an English translation of quatrains by the 11th-century Persian poet and mathematician Omar Khayyám. The book appears twice in this exhibition: in this painting of the bedroom, and in its own small painting where we see it from an oblique bird’s-eye view, the book cover like a painstakingly painted, rich Persian carpet. Like this book of poems, Suss’ paintings are translations showing domestic items and places filtered, and flattened, through time and memory.

Suss recently began fabricating in ceramic some of the books and other objects/clues we see in the paintings. These low-fire ceramic books, sculptural busts or heads, and wavy-edged vases rest on the floor around the gallery–often, but not always, near a painting in which the same object also appears. The clues add up to some understanding about the expansive intellectual and cultural life of the people who lived in the homes recreated in these paintings. They enjoyed fine interior design and art, travel, links to Jewish heritage and literature. In short, the inventory Suss offers confirms the “comfort…fitness to purpose…individual expression” and general “good design” sought out and achieved by many upper class families in post-WWII USA. We are looking at classed spaces and even racialized spaces, as so much of the new suburbs were racially homogenized by policies ensuring that suburbia remained for whites only.

Courtesy the artist and Fleisher/Ollman, Philadelphia. Photo by Aaron Igler.

Outside the picture window in “Dining Room (Verve Magazine, vol. 1, nos. 1 and 2)” (2015), we see the manicured shrubs and stone patio of this suburban landscape. Inside: the family dining room and yet more objects/clues, such as the golden, three-tiered vase filled with dark orange tiger lilies. This vase is echoed in the shapes of the curved backs of the Danish Modern dining chairs, in the manicured shrubbery outside the window, and yet again in the real-world ceramic vases that rest on the gallery floor nearby. This object, and its shape, so insistently reverberates that it becomes something of an emissary moving with ease among all the eras and places that Suss explores. The mobility of these objects is an interesting counterpoint to a viewing experience that is firmly held at the well-designed surface of the picture plane.

Suss’ grandparents’ house was eventually demolished to make way for a McMansion, a different version of the American suburban dream. Suss noted that afterwards the family was “saddled with stuff.” And this is the stuff we see: the detailed inventory of family objects, recreated in ceramic or painted into interior scenes so exquisitely designed and executed as to bring back into sharp focus all that has faded. And because people are strikingly absent in these works, the vase and furniture, coffee mugs, and objects become their stand-ins, much as a chair or map in a 17th-century Dutch genre painting may signal the life and body of a man away at sea. However, unlike in the Dutch example, these hard-edged, clinical paintings make no accommodations for a human’s soft body or messy emotions.

David Raizman, History of Modern Design, 2nd edition (Pearson Prentice Hall: Saddle River, NJ, 2004), 256-259, and 323.