In 2013, Fairhill Elementary School—in a largely Latino neighborhood near Temple University—was one of two dozen public schools shut down by the Philadelphia School Reform Commission. Artist Pepón Osorio biked past Fairhill on his daily commute to Tyler School of Art and began reflecting on the physical structure of the building. In an interview, the artist described it as “a huge architectural skeleton in the middle of a community”. He started discussing the school’s closing with Tim Gibbon, an artist and former teacher at Fairhill. While the physicality of the school struck Osorio, he became more interested in the people affected by its closing.

Starting with closure

In December 2014, he and Gibbon hosted a Fairhill School reunion at Tyler. The only agenda was to bring people together and share a meal. Yet even that simple action was profound. “There was an urge among the former students to come together again under the same roof,” Osorio explains. Later, they took a class picture in front of Fairhill—a significant memento for the youth who never felt closure with the loss of their school.

Osorio, a professor of art and co-chair of the Community Arts Program at Tyler—as well as a 1999 MacArthur Fellow, former social worker, and internationally celebrated artist—roots his artistic process in community. For decades, he has been committed to a dialogical approach to art-making that explores the cultural, political, and social contexts in which we live, with participation a key aspect of his work.

Committed to continuing the conversation sparked at the reunion, Osorio began meeting regularly with 10-12 of the former students. They would come together at Tyler on Saturday afternoons, their conversations becoming more nuanced the more they met. He explains: “Over time, I slowly introduced criticality into our conversations by asking questions, such as, ‘What does it mean to have a disrupted education?’ At first, the kids weren’t very interested in talking about this. But as they started to realize that the school wasn’t coming back, they became more engaged.”

A kind of summer school

In the spring of 2015, they turned their conversation into something more tangible. Teaming up with Temple Contemporary and securing a substantial grant from the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, they started conceptualizing how to translate the emotional aspects of the school’s closing—frustration, pain, deception, longing—into visual imagery. Osorio was particularly inspired by the idea of layering communities on top of one another, placing a school within a school to prompt questions about public education, historical legacies, and civil activism. With stipends from Temple, the youth could spend their summer working on the project. From Monday to Thursday all summer, Osorio and the youth met, conversed, and worked.

The installation—nearly 80 percent of which is made up of materials recovered from the school—is extraordinary. Entering the exhibition, you pass through a cubby-lined hallway filled with backpacks and coats, as well as Fairhill’s taxidermied mascot on a pile of books. Photographs documenting the project’s process, including the class reunion photo, line the wall above. Turning the corner, you are greeted by a smiling, life-size image of Fairhill’s former principal on the door, and upon entering the converted studio space, you encounter what can only be described as a fantastical classroom.

Conversing with loss

Every inch of the windowless room is covered in color, texture, and language. One corner is a miniature science lab; a section of the floor is filled with books on Mayan symbolism and US history; and a wall is lined with sculptural pencils topped with the faces of the participating youth peering out from digital tablets. On the back wall is the letter sent to parents announcing the closing of the school. And in the middle of the room are two large tables covered with chalkboards and chalk, surrounded by chairs for visitors to sit down and take it all in.

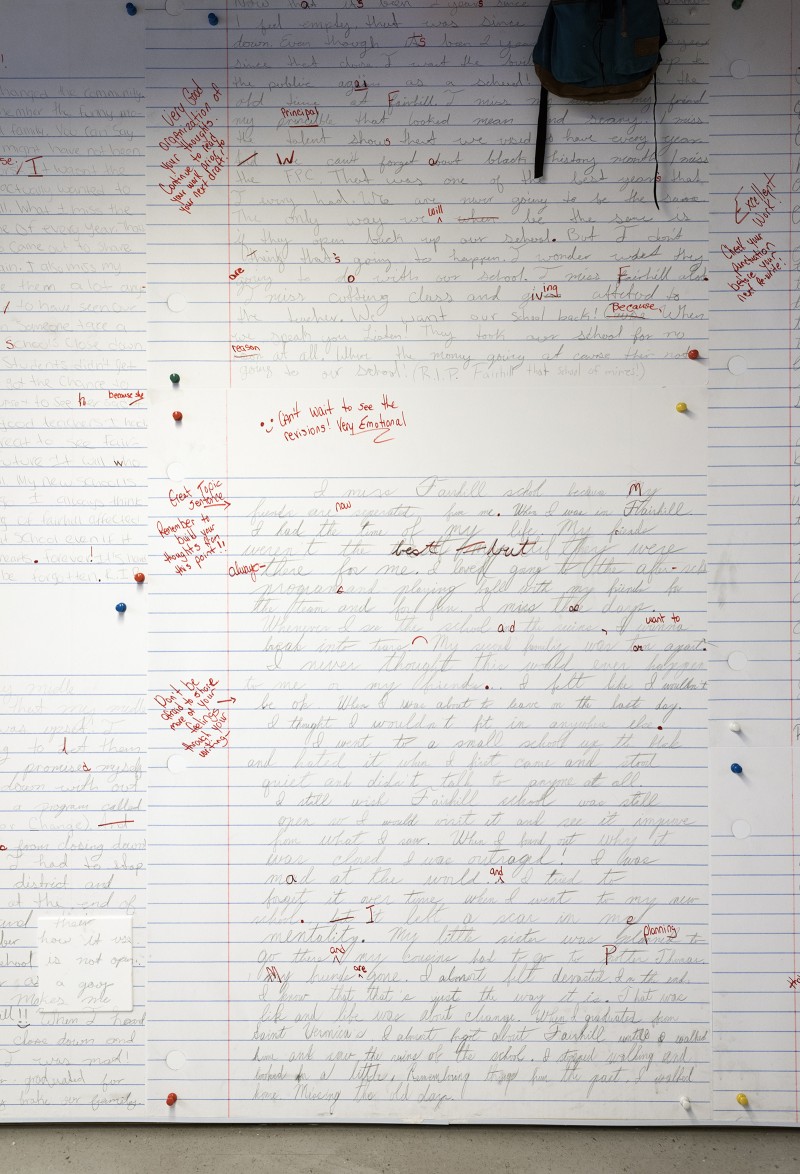

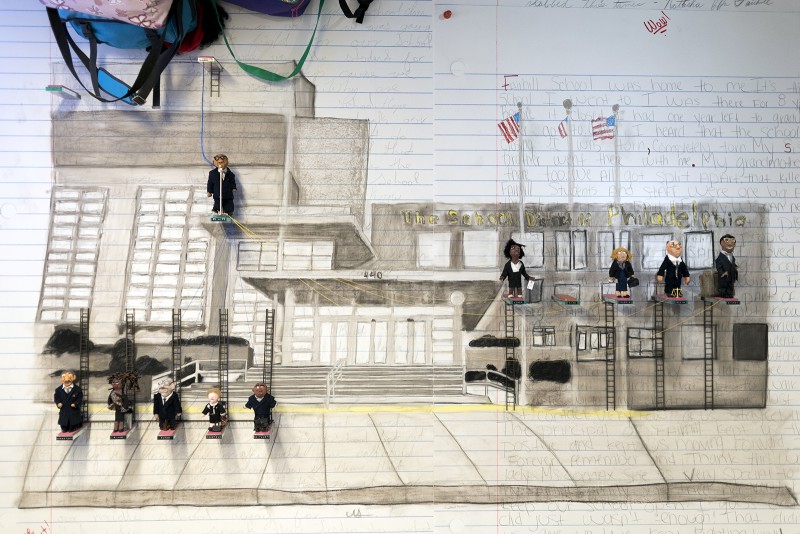

The space had to be a classroom for Tyler students; an exhibition site; and a space for the students to continue gathering on Saturdays. With these functionalities decided, Osorio and the youth went to work. Early in the process, the former students wrote essays on how they felt about Fairhill’s closing, their sentences becoming the installation’s wallpaper.

The essays—complete with teachers’ red marks and encouraging words—include consistent reference to memory and loss. One essay ends: “I want nothing more than for my school to be reopened and memories restored.” This reference to memory is one of the most compelling aspects of reForm. The installation provides, as Osorio puts it, “a landscape of memory”. Indeed, the reflection on this past event—the school’s closing—in the present moment becomes a direct negotiation with the students’ futures and gives Fairhill its own historical memory.

Acceptance and adulthood

The youth and their voices make up the most poignant component through multiple videos around the classroom. Permeating the room is the refrain, “When we speak, you listen,” which the 12 youth repeat in a powerful chorus. For Osorio, the poem, written by one of the students, reflects the realization that they are becoming adults—saying it is time you listen to us.

In many ways, it is also about the youth listening to themselves and thinking through their realities. At first, the responsibility was mostly on Osorio to translate the school’s closing into visual imagery. Then, the responsibility shifted on to the youth to act. “In the end, it is all about the youth seeing themselves as part of the larger world,” Osorio says.

Indeed, the youth are taking on this responsibility and continuing to develop projects. For example, they are currently working with artist Grimaldi Baez to create lie detector tests and conduct interviews about education with local citizens. Tim Gibbon is placing public memorials at other schools that were closed in 2013. Film screenings are being planned and speakers on education reform have been invited.

For everyone involved with reForm, there was a commitment to work on the project until closure was reached. From dialogue, listening together became their greatest asset. And out of the desire to keep talking, art happened. The beauty of reForm is that the intent to create closure led to so many beginnings.

What also makes the installation compelling is its ability to balance emotions. It makes you smile at the same time that it induces sadness. And rather than overwhelm you, the room’s material excess enables engagement, the embedded metaphors becoming more complex as we contemplate each object. In the end, reForm is about stepping into a work of art that is also a classroom and a memorial and a meeting room and reflecting on what it means. While there is no doubt that you will be aesthetically captivated, you will also, hopefully, respond to its criticality.

reForm will be on view through May 2016 in Room B85 at Tyler School of Art. It is open Thursday-Sunday from 12-5 pm and by appointment. Admission is free.