What is an appropriate monument for the current city of Philadelphia?

This is the question Monument Lab posed to Philadelphians this past summer and examined through a series of talks and public forums held at City Hall and elsewhere.

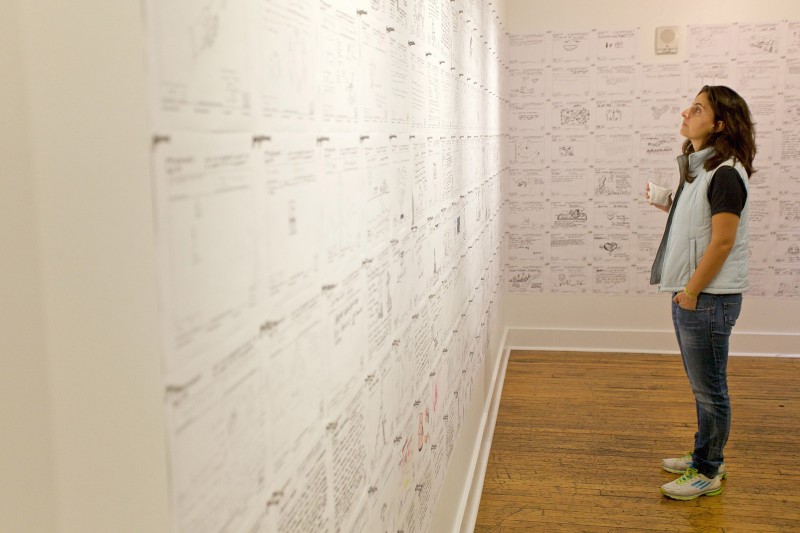

During these talks, Philadelphians were asked to propose what they thought to be an “appropriate monument” for the City of Brotherly Love. Monument Lab digitized and uploaded their research into what monuments the community would like to see on its website. These proposals—several hundred in all—are available online alongside an exhibition of submission highlights currently on display at the Philadelphia Center for Architecture. With over 600 proposals submitted during the research phase of the Monument Lab’s study, there is plenty for the viewer to digest.

The good, the bad, and the ugly

Monument Lab printed a supplemental newspaper at the commencement of these talks to examine what constitutes a monument that is reflective of the city at present. You can pick up a copy of the broadsheet at the Center for Architecture or read it online.

One the more poignant questions in the newspaper asks readers how we as a city grapple with the influx of persons moving into Philadelphia and the resulting gentrification that ensues. Further, how do we create a monument that is true to the positive and negative implications of this recent surge in population?

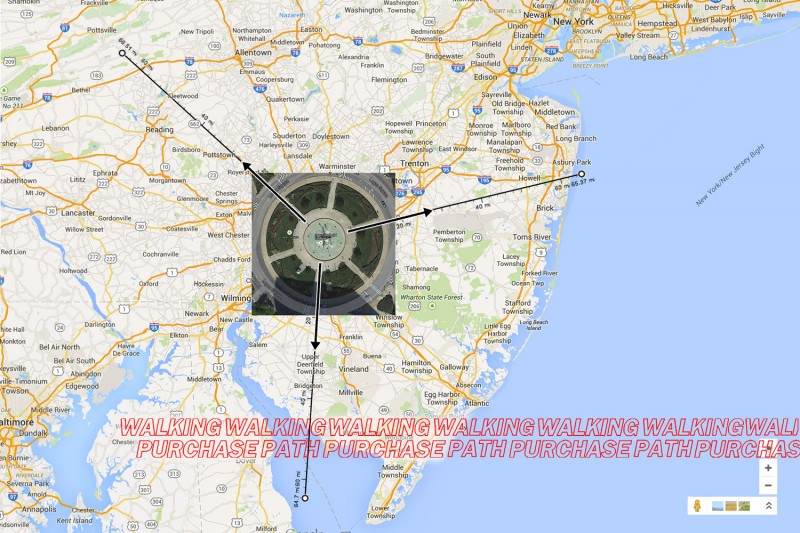

Also in the newspaper, artist and activist Zoe Strauss supposes a monument at Logan Square called “The Walking Purchase Path,” commemorating the story of James Logan, who forged William Penn’s signature “on a deed stating that whatever distance a man could walk in a day and a half… would belong to the Pennsylvania settlers.” A story not often told, Logan’s act dissolved previous agreements with the Lenape and stole their land from them.

Strauss’s proposal outlines three, 65-mile paths that lead out of the city with a manhole-sized marker at each mile to describe the ownership of the land at the time of Logan’s swindle This unrealistic idea, proposing 195 manhole-markers in all, draws attention to the history of theft rooted in Philadelphia’s history and creates a collective consciousness about unjust land developments across the city as of late.

Progressive push

Of the hundreds of public submissions for Monument Lab’s research, many hone in on encouraging an honest self-awareness about Philly’s complex history. Take proposal number 41, called “Unforgetting and Reconnecting”—a monument proposed for the intersection of 8th and Vine Streets to commemorate a forgotten African-American burial ground. Proposal 41 aims to extend its scope to commemorate old burial grounds and closed schools as a means of emphasizing the historical, and current, neglect of communities of color in Philadelphia.

A majority of the proposals harp on the city’s need to illuminate Philadelphia’s true history. One that stands out is proposal number 688, simply called “…”, in which the individual calls for the removal of all current city monuments in attempts to eliminate the limited history they construct. By removing these structures, it draws attention to the inconsistent narrative the city has constructed with its public works and calls the public to reimagine how we as a city tell our history.

In an equally radical proposal called “Lucretia Mott’s Un-Monument,” the individual suggests a three-step process. First, the city is to design a monument commemorating Lucretia Mott as a pioneer of women’s rights and the fight against slavery. Then, the city is to not construct the structure, as Mott was a Quaker and lived a simple and practical life. Finally, all funds allotted for construction are to be donated to support racial and gender equality.

Each of these submissions highlights a progressive air about Philadelphians, who crave an honest dialogue about our past. Some recent issues that are still raw and, perhaps, ripe for monumentalizing are: the thousands of graves previously housed on Temple University’s campus; and the 1985 bombing by the city of the MOVE collective on Osage Avenue.

So what is an appropriate monument for Philadelphia? After viewing and reading Monument Lab’s research, it becomes clear that there is no solitary structure that can do this city’s history justice. Instead, this exhibition and series of talks posits that a socially aware monument develops out of an interaction with the diverse communities that call this city home.

We are left to wonder whether or not curators Paul Farber, Ken Lum, and A. Will Brown intend for any of these projects to come to fruition. The more likely scenario is that these proposals are a part of a sociological survey to inform the production of a future monument reflective of the community’s view of what an appropriate monument is for Philadelphia at present.

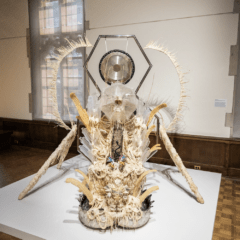

Interestingly, the group realized a temporary monument this past summer: the late Philadelphia artist Terry Adkins’ “Prototype Monument for Center Square”. Adkins—a University of Pennsylvania professor of art whose work was about memorializing hidden histories—envisioned a monument to a Lancaster County one-room schoolhouse. Monument Lab constructed the piece, out of repurposed wood, to resemble the bare-bones skeleton of an old-timey classroom. The work, which was installed in City Hall’s courtyard from May 15 – June 7, 2015, honored the late sculptor and fulfilled his vision to honor hidden history.

The Monument Lab proposal installation took place during Design Philadelphia at The Philadelphia Center for Architecture, located at 1218 Arch Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107.