Two photographers now comfortably members of the “old guard” of human-focused street photography, Joel Meyerowitz and Bruce Davidson, have just visited or revisited a very different chapter of their work in new books—landscape photography. While these pictures still occasionally contain people, their role is less central, more ingrained into the fabric of their surroundings.

Cape Light: Color Photographs by Joel Meyerowitz (Aperture, 2015)

For artists of every medium, the natural world has often served as a source of infinite mystery and knowledge to be gained. Even more than vessels for learning, the landscapes that surround us are places where we go to find peace, tranquility, and the confirmation of order in the world when we’ve been overwhelmed with the anxiety of our constructed environments.

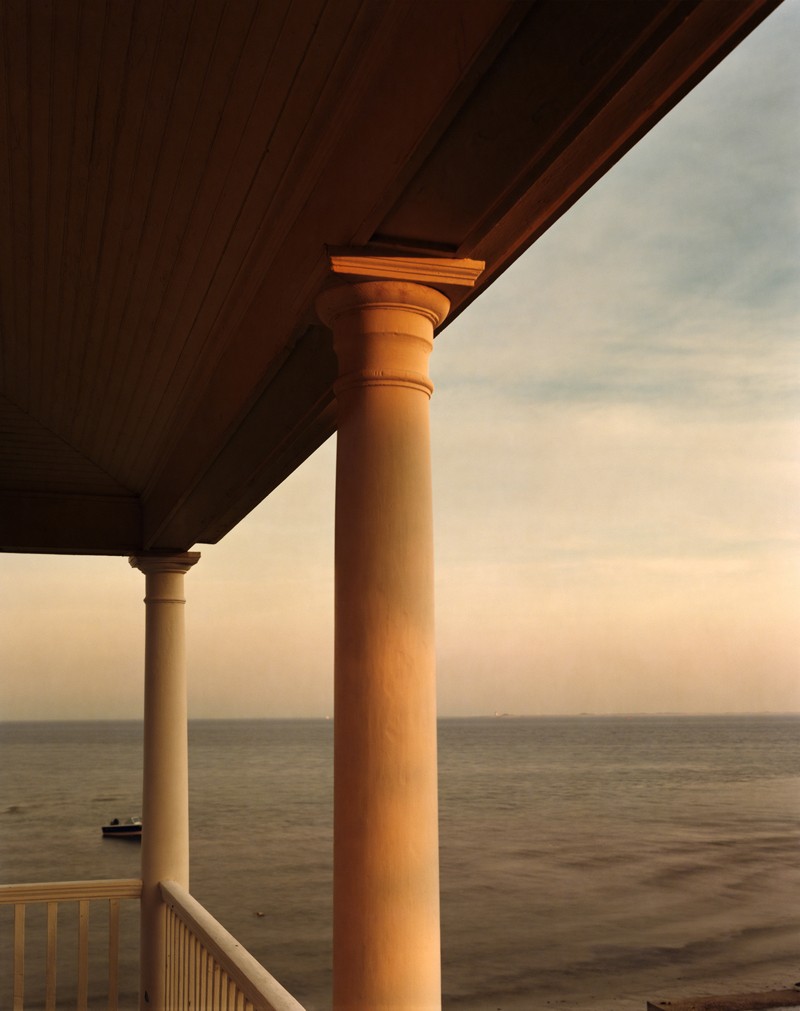

Aperture brings us a reprinting of one of color landscape photography’s classic publications, Cape Light by Joel Meyerowitz (originally published 1978). An earnest study of light on every surface around Cape Cod, Massachusetts, the book is the product of a sojourn away from the bustling streets of New York City where Meyerowitz made his name. True to its subject matter, Cape Light feels like vacation.

The pictures within are gentle, filled with emotion and nostalgia. They emit a both a sense of familiarity and the attention to beauty in plain sight that can best be found by a first-time visitor.

This work embodies a pure and carefree breed of Americana, where leisure rules and anything more complicated recedes into the ocean with the lapping waves. It is clearly of another era, a bubble ignorant of the racial and social divides that made it so appealing to vacationers in the 1970s. That being said, Meyerowitz wasn’t trying to make any kind of social statement with this work—just focus on the light, sky, and water.

Thanks to new, high-quality digital scans of the original negatives, the prints radiate deep, sensual color and clarity. In his foreword to the book, Meyerowitz describes the two summers he spent photographing here with his large-format camera as “joyous and feverish”. It’s clear that he was hyperaware of the tranquility of this place as compared to the streets to which he would soon return.

One of the more successful elements of the book is the passing of time as illustrated through multiple pictures of the same scene taken at various times of the day. Morning light, afternoon glare, and the thick blue cover of duskfall evoke the seemingly slowed passage of time when you’re near the ocean, and make the scenes anything but static.

Los Angeles 1964 by Bruce Davidson (Steidl)

Way over on the West Coast, Davidson’s two books, Los Angeles 1964 and Nature of Los Angeles 2008-2013, both printed by Steidl, offer differing views of the same city, though each aims an eye at the physical city itself and its surrounding hills and valleys.

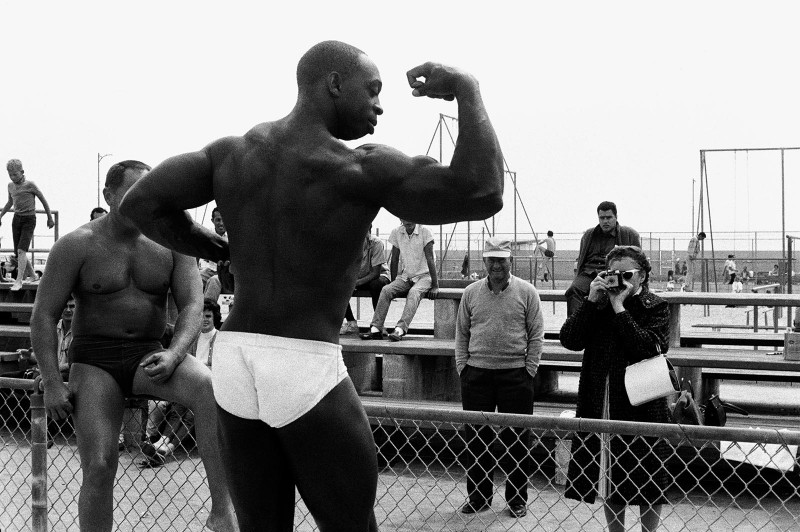

Los Angeles 1964 is a collection of previously unpublished pictures from an assignment Davidson shot for Esquire. Tossed in a drawer and forgotten for decades after the work was nixed by the magazine’s editors for what Davidson says are reasons unknown, his images frame the Los Angeles that most of us have come to know through fantasized Hollywood depictions.

This is a golden age of vast shimmering freeways where beautiful women drive in polished convertibles, drive-in burger joints are the chapels of youth culture, and palm trees still thrive unchecked in the desert, irrigated by faraway reservoirs. Even in this chromed veneer, the pictures find a hollow interior in the city’s people and places, capturing them when their guard is down and materiality shows through.

The work is reminiscent of Ed Ruscha’s books about Los Angeles, some also recently reprinted by Steidl. His projects, like Los Angeles Apartments and Twentysix Gasoline Stations, also explored the city through its architectural landscape, painting a similarly two-sided picture of reality in the city and how it presents itself to the outside world.

Nature of Los Angeles 2008 – 2013 by Bruce Davidson (Steidl)

Nature of Los Angeles 2008-2013 sees Davidson revisit the city and indulge in a newfound fascination for the “exotic, even erotic” plant life that peppers the arid epidermis of LA. Davidson reveals a poignant connection between these botanicals thriving in dry dirt thanks to distant water supplies and the wealth enjoyed by the LA elite in a city otherwise plagued by crime, poverty, and superficiality. A few of the pictures offer wry, ironic commentary both visually and conceptually, but a number of the others just seem too distant—the juxtapositions a little too easily deciphered.

All three of these books represent departures for their creators. Photographers have always turned to natural (or unnatural) environments for inspiration and probably always will, often when they become overwhelmed or discouraged by the anxious hum of the city. As it was for them, for me, this work is not just a visual but a mental respite from an oversaturated visual culture.