I was watching an old Homeland episode last week, which, like all Homeland episodes, began with outtakes translated into the grainy jumpiness of black-and-white surveillance footage and crackling sound bites, plus a musical score of pulsating uneasiness.

The package of graininess, jumpiness, and scratchiness were suddenly all too familiar because my Homeland viewing came several days after the terrorist attacks in Paris. Much like 9/11 video footage, the video from the Paris attacks played over and over on the television, some of it grainy, gray surveillance tapes, some of it vivid, from cell phones and other sources.

Gritty visuals and outlandish color

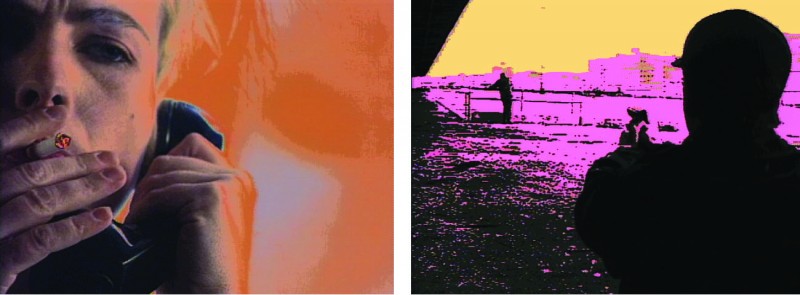

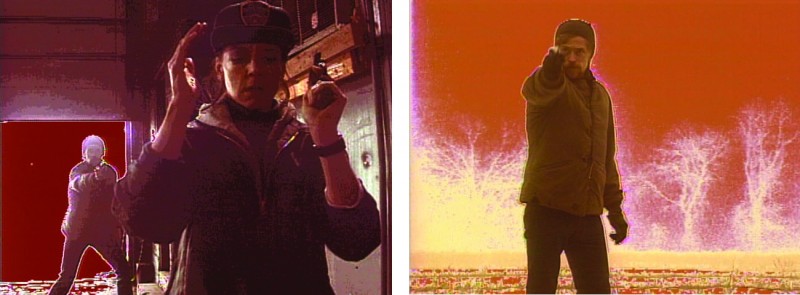

The Homeland intro was all to familiar for still another reason. Between real-life Paris reports and TV’s Homeland, I went to a screening of “White Homeland Commando” at International House. “Commando” is the Wooster Group’s 1992 groundbreaking digital-video parody of TV cop shows like Hill Street Blues and Law & Order. “Commando” tells the story of a New York wing-nut political cell infiltrated by police. The police and their targets all perform similar activities and behave erratically and irrationally in similar ways. The action is circular, replayed over and over with the actors switching who’s talking to whom inside a smoky room, who enters with a gun, etc. By the end, no one is left standing. Michael Kirby’s script is not so much a plot as a series of conversations, their circularity reflected in a series of visual motifs—not only surveillance-like black-and-white grainy jumpiness with crackling sound, gritty scenery, and compressed, depressed spaces, but also unreal, brilliant swatches of color laid over sections of the grim cityscapes. The color interrupts and redefines the gritty spaces with a gorgeous calmness.

The direction, by Wooster Group’s Elizabeth LeCompte, is experimental, a way to explore how theatrical ideas might operate in the new medium, she suggested after the screening.

No heroes here

Because “Commando” uses the TV vocabulary of true-crime shows, it seems to promise edge-of-your-seat entertainment along with the formal and theatrical elements. But that is not the case. “Commando” is sometimes satisfying visually and sometimes amusing theatrically. But it’s cool as a cucumber—kind of like a gray Jasper Johns American flag—the color and patriotism drained. “Commando” is a formal ritual without much drive or passion. The main statement is the absurdity of good guys vs. bad guys. Everyone is a schmo. No one’s a hero.

The script draws on real-life propaganda gleaned from sources like “The Aryan Nation Archives” and the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith’s Bulletin. The movie does not take a position on this loaded content. Like I said, cool. The shows being parodied are anything but cool. On TV true-crime shows, sometimes the good guys do bad things, but they are always the good guys, saving the world.

The discussion that followed the screening—LeCompte, plus the ICA’s Anthony Elms, and Electronic Arts Intermix’s Rebecca Cleman, the discussion leader—focused on the form, as if the medium itself had no message, let alone the script. In other words, the discussion never touched on good and evil. It touched on how shots were framed and planned and played with, which LeCompte said was the intent.

LeCompte described her stance and the film’s as amoral, rather than immoral, in response to an audience question about the film’s implications. But the characters in the movie (one of them played by actor Willem Dafoe) are not cool. They worry; they rant; they argue. They are lost souls in a pitiless gritty city adorned with beautiful splashes of unnatural color. The formal parody deracinates them—saps them of their emotional draw. The language of hatred becomes the sideshow, while, without giving a damn, we watch the cell members and its infiltrators self-destruct. In a way, the movie becomes a lesson in why TV plots and characters are so broadly drawn, with the arty visual effects subservient to the storytelling. The story needs to stand up and out in such a nimble, vigorous environment. I was struck by how differently a ritual of destruction and futility would play out on a theater stage.

Changing times, familiar fears

The formal approach undercuts any moral vision—that some people and some acts and some speech are more heinous than others. The video was made nine years before 9/11. I wonder if it could possibly get made today in this country.

Now 24 years later, we are still watching TV shows with surveillance themes—not a surprise given real life, Edward Snowden, England’s CCTV. The subject is touchier; the iconography, techniques, and paranoiac fear of and justification for surveillance are the same.

Surveillance video—real and fictional—provide a kind of double-consciousness. Surveillance is invasive, as it creates the illusion of safety. We look to the tapes of terrorism and crime events for information and reassurance. But the surveillance video also plays into the terrorists’ goals of disrupting quotidian life and peace of mind. The more the videos replay, the more they disturb us. I presume that’s a terrorist’s dream—you will be very afraid. Homeland, unreal though it is, pretty much works the same way. The good guys aren’t so good. The surveillance is full of good news and bad news. And the secret cells and agencies are saving us, destroying us, and disturbing us all at once. We watch in part to play out our fears of an international situation gone wrong.

Viewed post-Paris, post 9/11, “White Homeland Commando,” for all its formal wizardry, seems both too long and almost offensively cool. Yet its use of the almost Germanic term “Homeland” precedes “W,” as well as the TV show Homeland. That’s not all that’s astonishing. After nearly a quarter of a century, the video’s visual vocabulary is fresh as paint.

For upcoming films at International House, go here.