For the first time in Philadelphia, Joan Tanner’s (1935- ) work is on view at Locks Gallery through Jan. 30. Having exhibited extensively in California since the 1960s, Tanner is a prolific artist who works with various media—concrete, building materials, oil stick, colored pencil, video, and photography—to generate large-scale sculptures and two-dimensional imagery. At Locks, guest curator Julien Robson selected works on paper from three series: Drawing Focus (1999), donttellmewhereibelong (2013-2015), and endofred (2015). Through the body of work, Tanner explores pictorial space in an abstract landscape, juxtaposing the ephemeral and the concrete: organic matter and industrial apparatuses, migratory transitions and grounded structures, suspended forms and tethered elements. I was not only intrigued by the compositional complexity of the works on paper, but by their poetic nuances, their imaginative scope, and their contemplative yet somewhat distorted constructions. Tanner’s imagery conveys a sense of beauty in the midst of strained conflict, a metaphor perhaps of the relationship between the natural world and human-derived systems.

Contradiction through layering

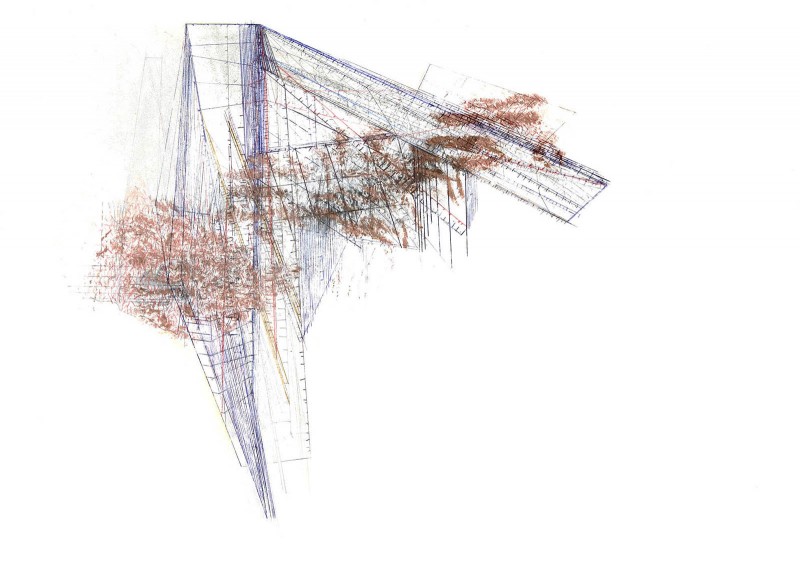

A straight-edged grid in donttellmewhereibelong #20 and #24 emphasizes a stringent aspect of human intervention. Compositionally central, the structural devices contain organic forms. In #20, a delicate architectural drawing of a steeply pitched roof-like design overlies umber marks resembling a forest of trees. The scumbled brown flecks indicate foliage during a moment of decay, and, with the absence of tree trunks, they float on the page unmoored by roots. The trees extend horizontally, but are not beyond the reach of the severely vertical exterior. In #24, sinuously shaped insect wings entwined with a human leg and foot (a toe appears on the bottom right) remain encased in thick pencil lines that hint at a geometric shape. The wings attempt to extend, but ultimately conform to the arrangement the graphite strokes delineate.

In #20 and #24, the edges of the structural formations are soft, suggesting that they regulate an indefinite realm. The linear forms are also dominant and visually obfuscate the landscape’s signs, fostering an intense layering method. In a 2014 interview, Tanner notes that in her work she engages “contradiction by layering and stacking disparate elements,” forces “illogical connectivity,” and aims to disrupt “assumptions about spatial relations.”** #20 and #24 suggest a tension, a suppression of animate organic components within the rigid condition of the human-made.

Compulsively revelatory

Similar to 19th-century Symbolist artist Gustave Moreau, Tanner’s donttellmewhereibelong provides an imaginative space—in her words, a geographic imponderable. Both Tanner’s and Moreau’s respective works explore modern life through a system of suggestive symbols that belie conclusive meaning. Upon seeing a Moreau exhibition, critic Joris-Karl Huysmans wrote that Moreau’s jewel-like color intoxicated him and caused him to transport to “distant realms.”* After reaching a mind-altering state, the critic groped his way out of the gallery and regained consciousness on the Paris streets. Upon return from his imaginative experience, he became keenly aware of the fallacy of his present-day circumstance and was met with the “ignoble” and “shameful” streets of his city. The process of making associative connections before an unresolved pictorial narrative caused the critic a momentary escape that led him to recognize Paris’s vile underbelly beneath the artificiality of its beautiful façade.

I find an analogous concept operating in Tanner’s body of work. The artist’s imagery offers a critique obliquely, not directly. The choice of medium elicits our senses and the incongruous visual elements provoke our participation. Like Moreau, she provides an experience through which we can arrive at meaning—generating compelling, visually charged works that are paradoxically fraught with anxious exchanges.

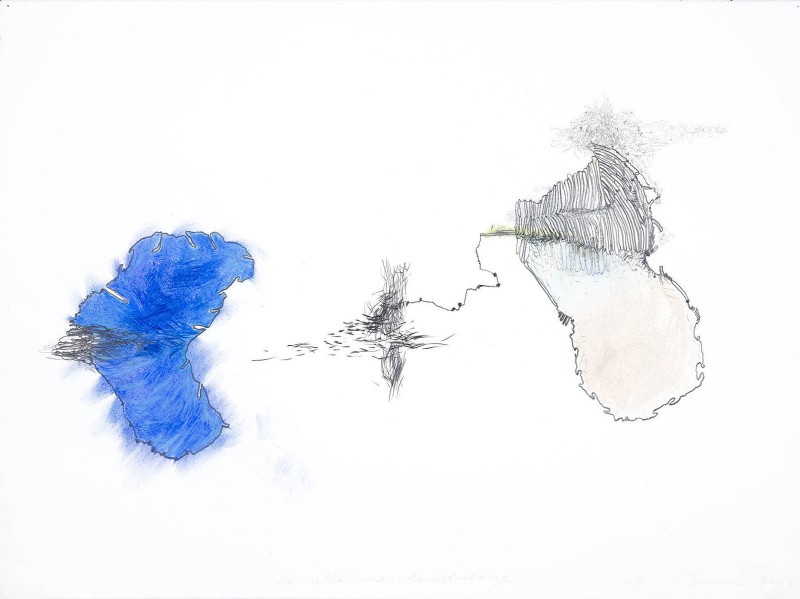

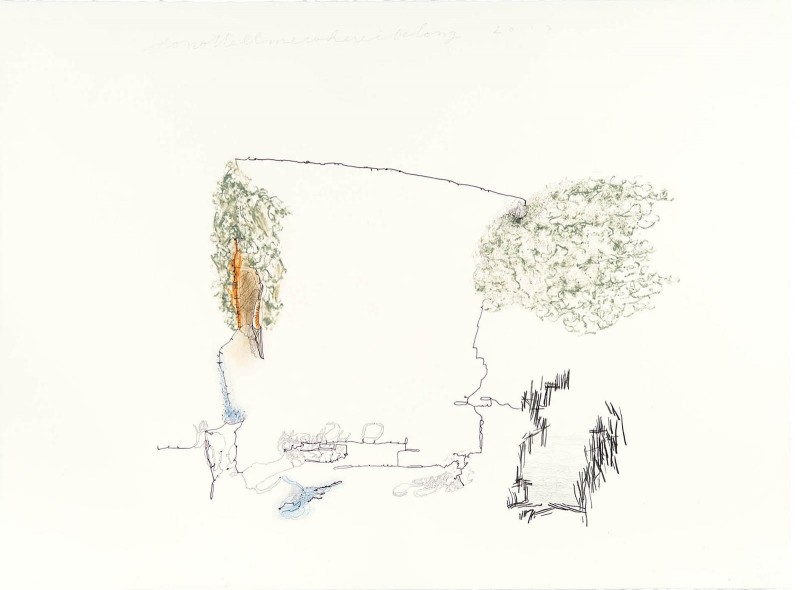

In donttellmewhereibelong #2, #3, and #6, a pictorial migration occurs. The images share a composition in which a gulf of negative space divides two distinct spheres. Between them, a series of fine and thick pencil strokes travel from one abstractly depicted place to another; a gravitational pull directed by the forms seems to chart their course. On their way, lines change direction, points provide map-like paths, and strokes follow a meandering route. Once the marks reside in the solid shapes, they shift in line quality from whimsical to geometric and become pictorially ensnared in the complex at which they have arrived.

In #2, for instance, light pencil marks seemingly made with a quick curvilinear stroke of the artist’s hand become the dense brick-like shapes that darken in value as they settle in the area on the far right. In #3, a weightless saturated-blue wing-like shape flies alongside a corresponding form; a series of points and hatch marks trail between them. Suspended between forms, the marks suggest the indeterminate situation in which we remain while in search of another. In following them from left to right, the graphite strokes transition into a maze-like network in the right-hand form, connoting the gradual reconfiguration necessary to enter into and conform to a new setting.

Conflict in connectivity

In #2 and #6, topographic systems ground the spheres. Just below the dense graphite marks (addressed above) in #2, there is a bird’s-eye view of a map composed of straight and winding lines similar to the outline of an American state bordered by a river. Running below between the sage-green marks in #6, an aerial perspective of a complex resembles a street-course imposed on a waterway. Although we observe the topographic elements from above, we look directly at the spheres of place. In this way, the artist compounded conventional spatial relationships and caused a disjointed visual process metaphorically akin to merging industrial and natural elements, such as a region’s boundary or a road over a creek.

Tanner’s works on paper are initially gorgeous, a respite for the senses. But fragile, awkward moments point to uncomfortable relationships between forms. In drawing together the associative elements, we encounter an abstract world rife with forced connections and weak infrastructures. Before her imagery, we can recognize that in seeking effective interconnectivity, we find difficulty, insecurity, and disruption—the conflicting notions we confront as we attempt to shape our environment.

There will be a reception at Locks Gallery on Friday, Jan. 22 from 5:30-7:30 pm, and both Tanner and Robson plan to attend.

* Joris-Karl Huysmans, Certains (1889), Symbolist Art Theories: A Critical Anthology, trans and ed. Henri Dorra (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1994), 44-47.

** Joan Tanner, interview by Nikki Grattan, In the Make: Studio Visits with West Coast Artists, June 2014.