“It has been said that, at its best, preservation engages the past in a conversation with the present over a mutual concern for the future.”

–William Murtagh, Keeping Time: The History and Theory of Preservation in America

The lost neighborhoods of west Philadelphia

Leroy Johnson’s Philadelphia is not the gleaming Comcast skyscrapers, the Constitution Center, the Barnes Foundation, or Dilworth Plaza. If you want to see his Philadelphia, ride the El through West Philadelphia, and after that, go see the exhibition of his work at the University City Arts League.

With the El as his viewing platform, Johnson, 78, who grew up in southwest Philadelphia, has produced a body of work inspired by neighborhoods in Philadelphia which, over time, the city has been losing to poverty, neglect, and sometimes to redevelopment. In his paintings, mixed-media works, and sculptures, Johnson captures the shapes, colors, and textures of the architecture and streetscapes and, to a lesser extent, the people of these neighborhoods. He captures the moods of the neighborhoods—their pace, pulse, and humanity. The result can be disturbing; it can also be beautiful.

When I saw Johnson’s work, I wondered whether it was about protest. I wondered whether he was commenting upon hyper-segregation in Philadelphia, about the racial divide, about the concentration of dense poverty in circumscribed areas of the city. When I spoke with him, however, it became clear that this was not his intention. Although his work depicts the sometimes harsh realities in those communities, Johnson sees himself as an historian, an educator, not a critic, not an activist. Indeed, in a sense he sees his art as an exercise in historic preservation. Johnson laments the tragic loss of neighborhoods, and the troubling lack of historic preservation in much of Philadelphia, but the artwork is not the product of an angry man. He has said that his work “speaks of change, growth, and humankind’s effect on the land”.

Leroy Johnson: The eyewitness

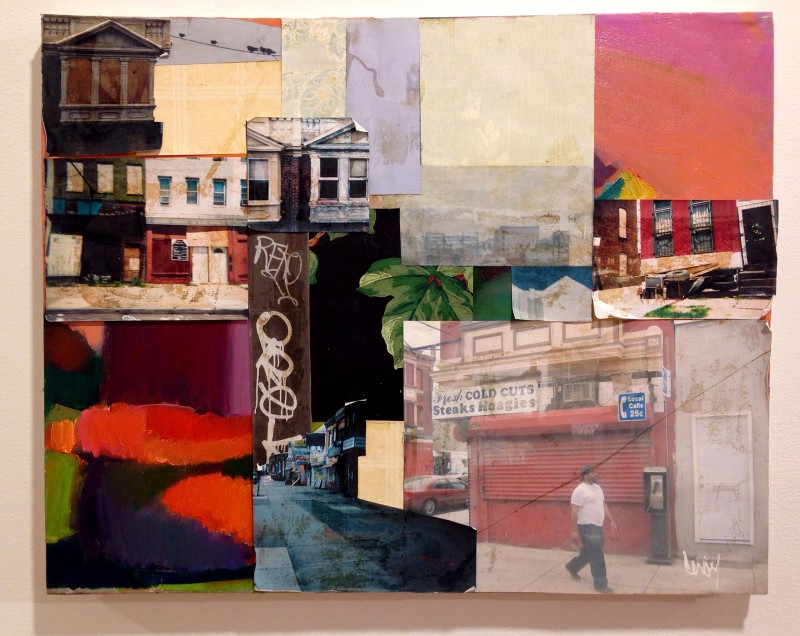

Johnson’s work—which he refers to as Urban Expressionism—is more abstract and less people-centric than that of many of his admired predecessors and contemporaries who have portrayed life in their African-American communities: artists like Jacob Lawrence, W.H. Johnson, Romare Bearden. Although much of his work integrates photography in collage, it is not street photorealistic, even though it depicts some of the same Philadelphia neighborhoods that remarkable street photographers, such as Jeffrey Strockbridge, Zoe Strauss, Ronald Corbin, and Daniel Taub have portrayed.

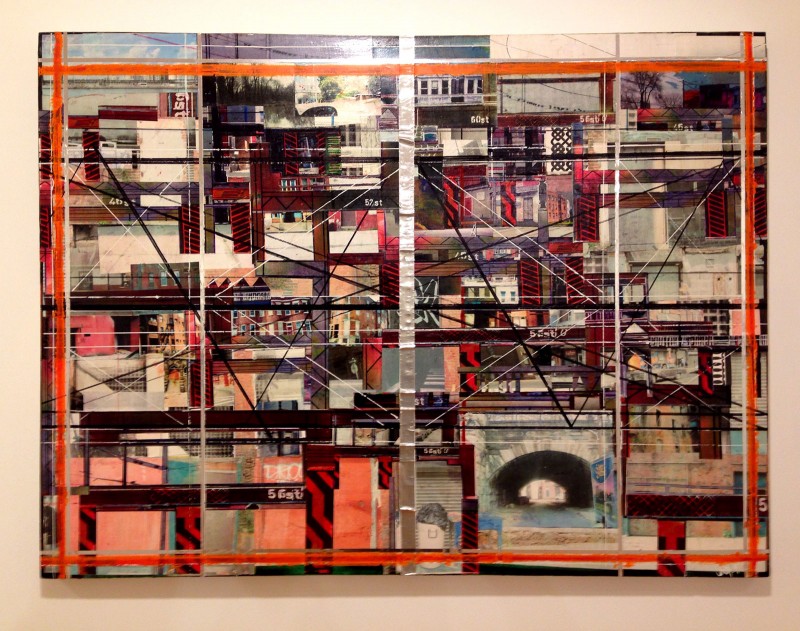

“The El to 62nd Street,” pictured above, is a striking example of Johnson’s work. The piece is laid out in street map grids, and within the grids lie Johnson’s impressions of those street blocks. As in any street map, people are, for the most part, absent. There actually is one person depicted in the piece, who seems to be walking off the canvas. The work makes you feel like you are walking through the back alleys of West Philadelphia: there are fire escapes, garbage cans, tunnels, gates, barricades, graffiti, signage and, as in so many of Johnson’s pieces, pigeons—which, as Johnson has pointed out, are always watching us. Johnson is a genius at composition: blending and stitching together these disparate elements of life with perfect aesthetic pitch. His work is like the improvised jazz that he loves.

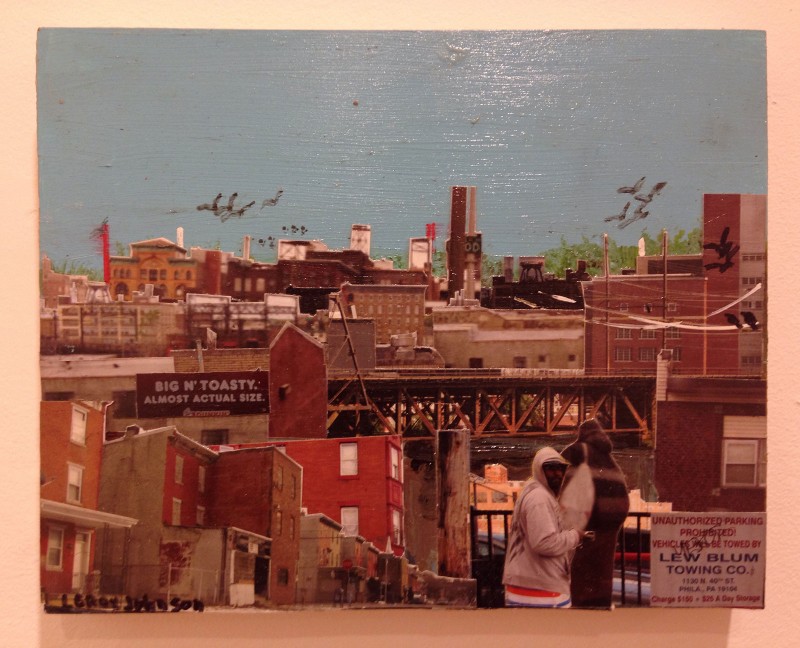

In a number of Johnson’s pieces in the exhibit, including “Eyewitness (medium blue sky),” there appears a young man wearing a gray hoodie. He is with a friend, and moving away from the viewer, but looking back over his shoulder. Leroy Johnson, of course, is the eyewitness here. But so is that man, who seems to be wondering whether he is being seen. And so are we, although too many of us have our eyes closed to the neighborhood worlds that Johnson is depicting, remembering, and trying to preserve. But if we open our eyes, or let Leroy Johnson open them for us, we become participants rather than witnesses, and there perhaps arises the hope of overcoming some of the barriers, some of the forces that separate us from those communities.

Although the theme is hardly predominant, Johnson’s work clearly touches upon the political history of African-Americans in this country. The work includes poignant scenes of death and despair in the African-American community, and suggestions of the oppression that the community has been subjected to. “Lynch Piece (with raised hands),” pictured here, a small wall sculpture, is the most blatant example. In other pieces, you find graffiti referencing Trayvon Martin, a photograph of Malcom X, riot police, a burned flag, mothers grieving over murdered sons, and crucifixes. Mr. Johnson may not be angry, but his eyes have not been closed, and he has something to teach that is not going to be found in the media.

Johnson’s commission for Philadelphia’s new Juvenile Justice Services Center

At the end of 2012, Leroy Johnson and fellow Philadelphia artist Sarah McEneany, two prominent artists who have been witnesses to changing neighborhoods in Philadelphia over many years, were chosen to contribute works to the new Juvenile Justice Services Center in West Philadelphia, at 48th and Haverford streets. Roberta Fallon reported on this in Artblog in January 2013, in an article titled “Art for the public and for the youth at the new Juvenile Justice Services Center,” and an article also appeared in Creative Philadelphia that December: “New Percent for Art Projects Dedicated at Juvenile Justice Service Center“. There is also a wonderful short film, “Red Brick, Green Grass, Blue Sky,” which was commissioned by the City’s Office of Arts, Culture, and the Creative Economy and produced by Greenhouse Media. The film follows Mr. Johnson and Sarah McEneaney as they create their public artworks for the project. It’s worth mentioning that the new Juvenile Justice Services Center replaced the old Youth Study Center, which was demolished on the site of what is now the Barnes Foundation.

I think it’s particularly appropriate, although unintended, that this exhibition coincides with Black History Month, in which we honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of African-Americans like Leroy Johnson in every area of endeavor throughout our history and remember the shameful history of the African diaspora. The University City Arts League also deserves recognition, not only for staging an exhibition like this, but for providing art education to disadvantaged children in the community. In fact, the League also promotes art education within the public schools of Philadelphia, which are as challenged as the neighborhoods that Mr. Johnson focuses upon in his work.

Leroy Johnson received his Master of Human Services from Lincoln University, and a degree in Drawing and Ceramics from the Philadelphia College of Art. Among many other things, he studied at the Fleisher Art Memorial, and he was a resident at the Fabric Workshop.

Eyewitness will be on display at The University City Arts League through March 18, 2016.