By A. K. Smithson

“Remembering, Repeating, and Working-Through” is a short but extraordinary paper written by Sigmund Freud in 1914. I have been reading it for years with unshaking enthusiasm. In it, Freud reminds the reader of the dramatic changes in psychoanalytic techniques. The paper begins with a note on hypnosis: as the first schematized psychoanalytic technique, hypnosis was used to resolve deep psychic repressions of the patient by bringing the traumatic experiences that constitute the patient’s symptoms to the surface.

The practice of hypnosis was quickly discarded by more cutting-edge techniques. In spite of the changes, the techniques grounding psychoanalysis as a clinical practice are all the same. They are all organized, according to Freud, by the attempt to “fill in the gaps” of a patient’s memory. Psychoanalysis is a technique of remembrance. Crucially, it is only by remembering that the patient can work through the anxieties that dislocate his/her psychic life. Furthermore, it is only in remembering that the patient can, as Freud notes, “overcome the resistances brought about by repression.”

There is a significant distinction between the practice of hypnosis and the more modern psychoanalytical techniques of Freud’s own manner of analysis, one that I think is important for my review: hypnosis creates a safe barrier between both the analyst and analysand, and the analysand and him/herself. It is the second point that is worth stressing. Hypnosis creates a barrier between the conscious everyday life of a patient and their deeper psychic repressions by staging the act of remembering as if it were only part of the patient’s past and not functioning in their present situation.

The modern technique is different from its predecessor in a specific way: it is more perilous. Freud provides us with a beautiful, yet disquieting, formulation of the distinction: “[the modern technique of psychoanalysis] means summoning up a chunk of real life, and cannot therefore always be harmless and free of risk.” The modern technique brings forth the raw messiness—violently, perhaps—of ordinary life (the word “chunks” is especially evocative and harrowing).

A fixed progression of images

The distinction between hypnosis and Freud’s technique of psychoanalysis immediately surfaced in my thoughts when I visited the elegantly presented exhibition of works by the artist Matt Mullican (b. 1951) at the Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery in Philadelphia. This is perhaps unsurprising. As is well known, Mullican has produced performances in which he carries out activities under the state of hypnosis. From a Freudian perspective, this means that Mullican revives a practice that, clinically, has been abandoned. I would like to suggest that the practice of hypnosis challenges Mullican’s work from within its own strategies.

I will concentrate on what I take to be the best work in the exhibition: “The Meaning of Things (who feels the most pain?)” (2014). I understand that such a restriction is problematic, not least because the exhibition presents a number of other works by Mullican that merit attention. If I focus on one work only, it is because I want to be faithful to its complexity.

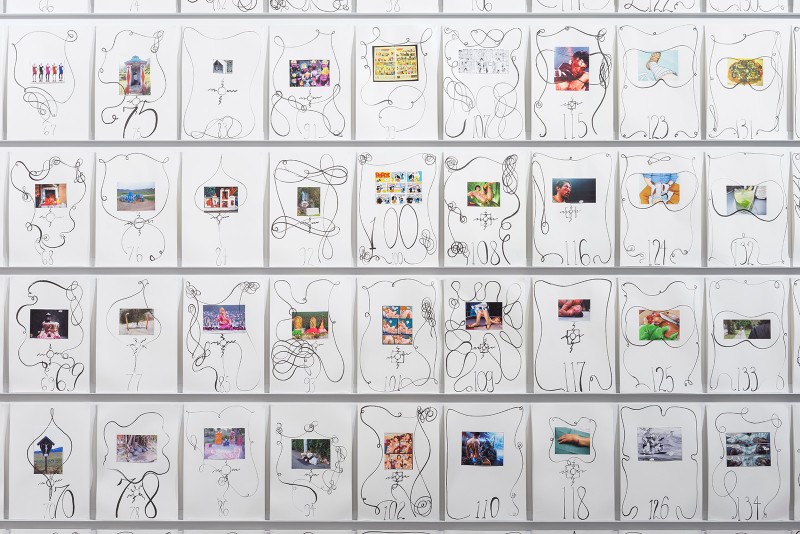

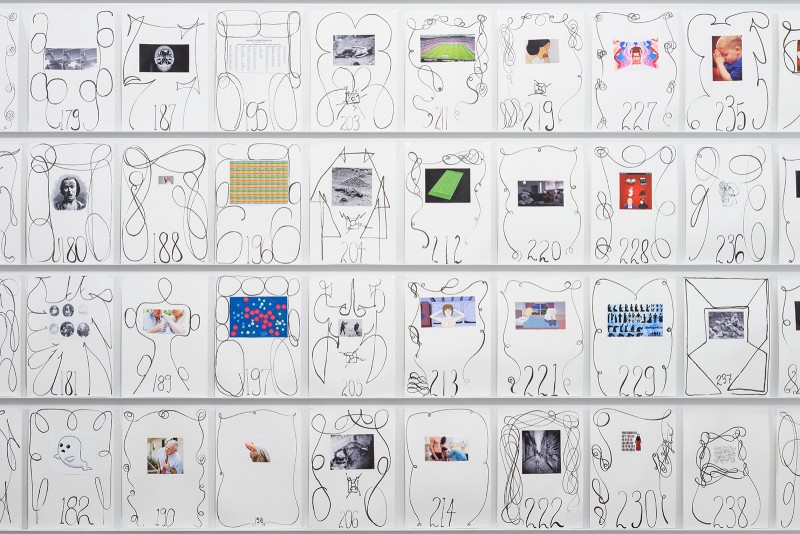

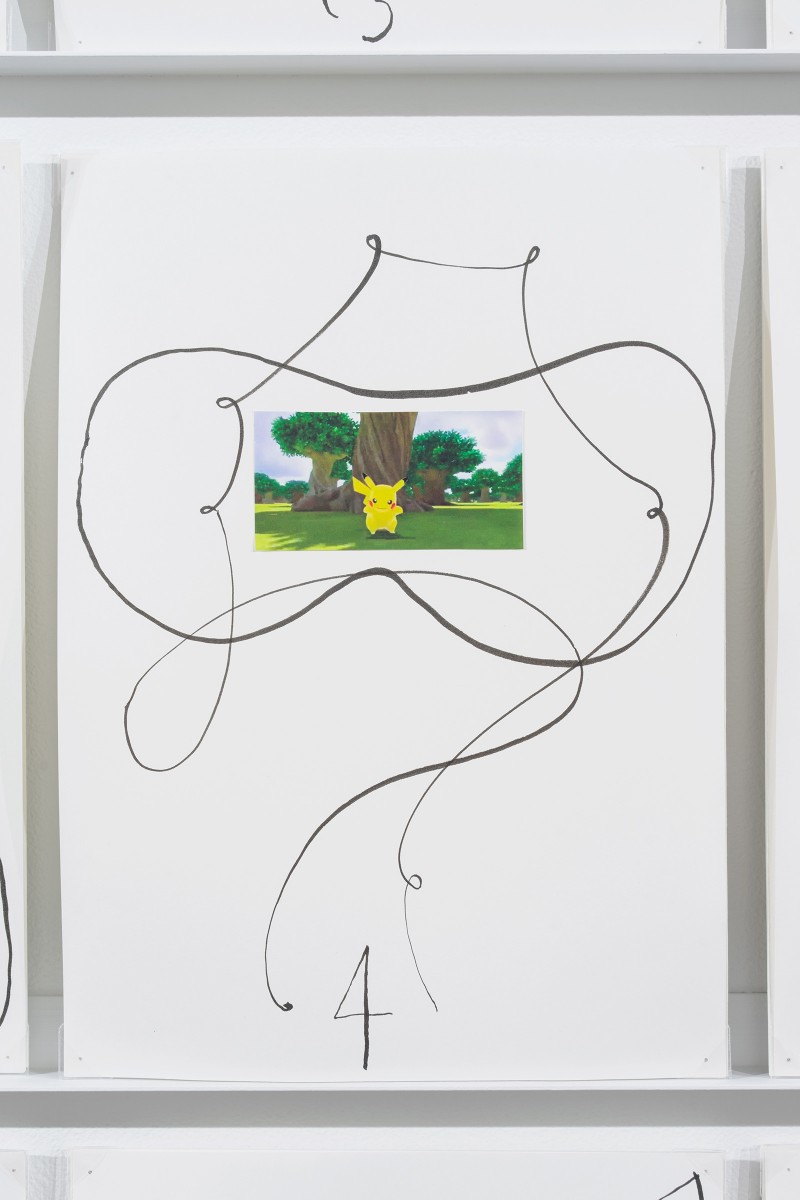

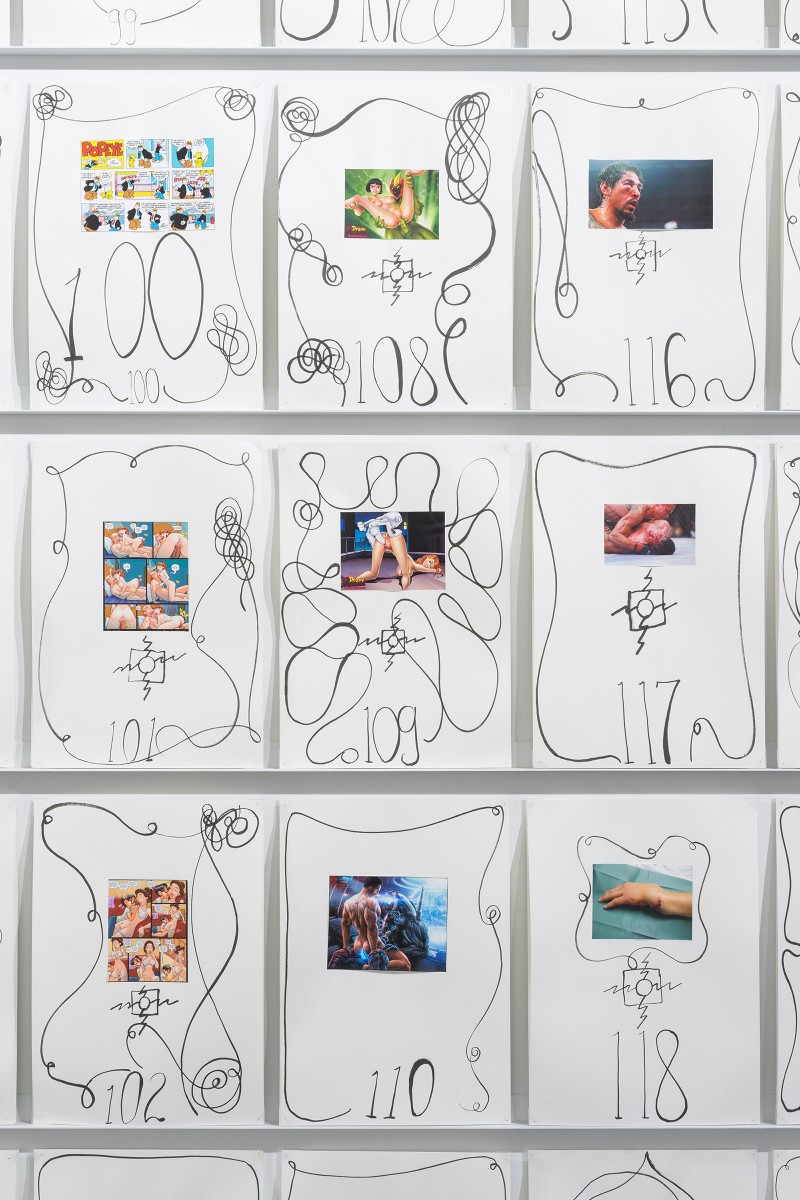

“The Meaning of Things” is the newest work in the exhibition (the earliest piece exhibited is from 1973). The work consists of 676 collages and texts on sheets of paper slightly smaller, if I recall correctly, than standard printing paper. At the approximate center of each individual sheet is a small image that appears to be a printout of an image procured from the Internet. Around the images are what I can only describe as hand-drawn, quasi-calligraphic marks (in black only) of different formal consistencies of line: some of the lines appear to be slightly shakier than others, some exhibit a more definite and confident application, some are thicker than others, etc. Almost all the lines are curved, that is, give the impression of an “organic” form in the manner of ornate, rococo frames.

There are immediately two things to note: the sense that the images are digital and have been located by the artist, taken out of their ethereal context and fixed onto a sheet of paper; second, the “quasi-calligraphic marks” that frame, interact, cut across and, at some points, overlay the images.

It is not insignificant that we (or at least, I) perceived the images Mullican presents as images taken from the Internet. I effortlessly assumed that the images came from the Internet. This is a problem, since it turns the Internet into a place that one can “source” images as if it were an archive that has a root or fixed base. But isn’t the Internet a “rhizomatic” structure, one in which there is no such “root”? I believe that Mullican is uninterested in the question of the “rhizomatic” nature of the Internet because he presents the images in a fixed, linear serial progression, starting unmistakably with an image that he numbers “1” (and numbering each other image in succession). This presentation of linear progression coerces the supposedly haptic, “free-floating” life of digital images into one of serial progression (an anti-rhizomatic form).

For Mullican, the digital image is not “free-floating”. Rather, he wants to nullify its existence in this state. What we have instead is a static image, suspended from its previously buoyant predicament (it is not by chance that the image is fixed at the approximate center of each sheet of paper). This fixing of a hitherto “unfixed,” “free-floating” image gives the work a precise implication. It suggests that the image is appropriate. Moreover, it suggests that image pre-exists the artist’s visual sensibility as someone who creates unique images like paintings, collages, photomontages, etc. The practice of the appropriated image recalls an established artistic maneuver that can be located in the works of Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol (to name only the most obvious).

Repetition and narrative impulse

Mullican’s images, however, are not re-worked in any way, at least not in an immediately recognizable way. They are not, for example, used as a photographic source for a silk-screen or as a reference for a larger painting. Instead, they appear to be printed out as if they were found in their exhibited state. This is at once highly unlikely but not wholly impossible. The images are all the same physical size as presented on the sheets of paper (which does not mean the same pixel size). This suggests that the artist modified them. The modification is, relative to the practices of American art of the 1950s and 1960s, slight and barely perceptible.

Mullican’s images circulate digitally. Therefore, they are images from an age in which the chemical-based photographic practices of yesteryear are almost completely liquidated. It is their digital nature that constitutes their life as circulated material. Chemical-based photographs circulate in a different context: they are produced in darkrooms, are printed on specific machines, are circulated manually by way of couriers, post-office staff, gallery assistants, relatives, etc. in specific modes of transportation (train, automobile, planes). Therefore, they have a more definite “objective” nature.

“88 Maps” (2010). Courtesy of the artist and Mai 36 Galerie. “The Meaning of Things” (2014). Courtesy of the artist and ProjecteSD. “Untitled (Indian Banner)” (1973). Courtesy of the artist and Mai 36 Galerie. Photo credit: Studio LHOOQ

The digital image, however, is made up of an algorithm, an elementary code of “0/1”. Its objective nature is different. This means that its conversion in printed form, in Mullican’s work, is not a logically anticipated maneuver (I would argue that we experience advertisements in different distributed forms like magazines and billboards as if they were still chemically produced images). We have a sense of the pixels that make up the images in Mullican’s work; we have a sense of his “cutting-and-pasting”. This all lends to our heightened experience that something is out of place, that something has been forced into another context in order to somehow express a reality or process that has been hidden.

What this “something” is brings us to the next dimension of the work, namely the marks that surround and interact with each image.

The marks on each sheet formally resemble the marks that Mullican made during his performances under hypnosis. Indeed, “The Meaning of Things” recalls these performances in more than simply formal ways. The repetitive nature of the drawings, for example, have the quality of, as Freud puts it, “acting out,” that is, the reproduction of psychic symptoms at the level of everyday activities free of the individual’s awareness that s/he is acting out. The repetitive nature of acting-out is not a mode of memory-work (an attempt to remember anything of what has been forgotten or repressed). Repetition is the manifestation of repression itself; it reveals deeper, psychic processes.

The repetitive nature of “The Meaning of Things” invokes the possibly infinite repetition of the digital images that circulate in cyberspace (think of “memes”). The meaning of being “bombarded” with endless images has become exacerbated in the context of the Internet. Digital images give the impression of an infinite realm, a kind of cosmic realm of endless reproduction and expansion. It is unsurprising that the sense of the infinite we get when we think about the Internet is mapped onto archaic energies that make up the essence of our existence. As is well known, these are, according to Freud, sex and death.

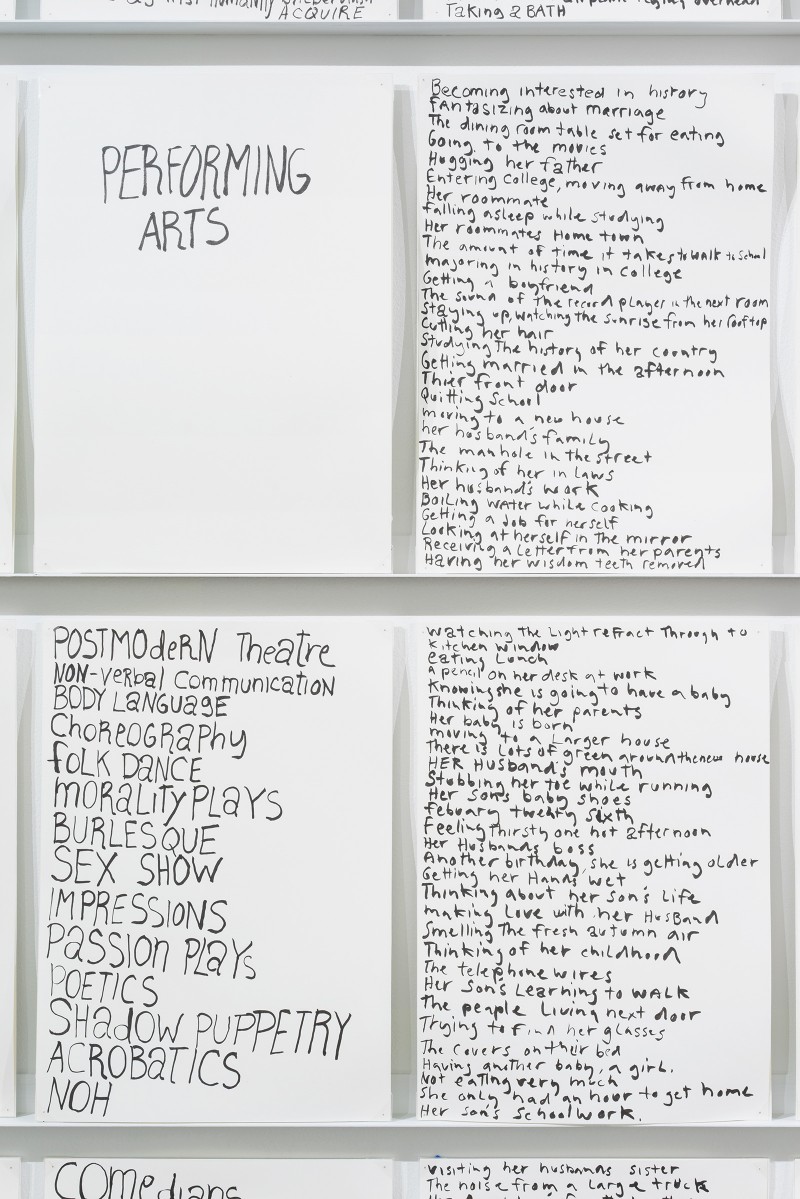

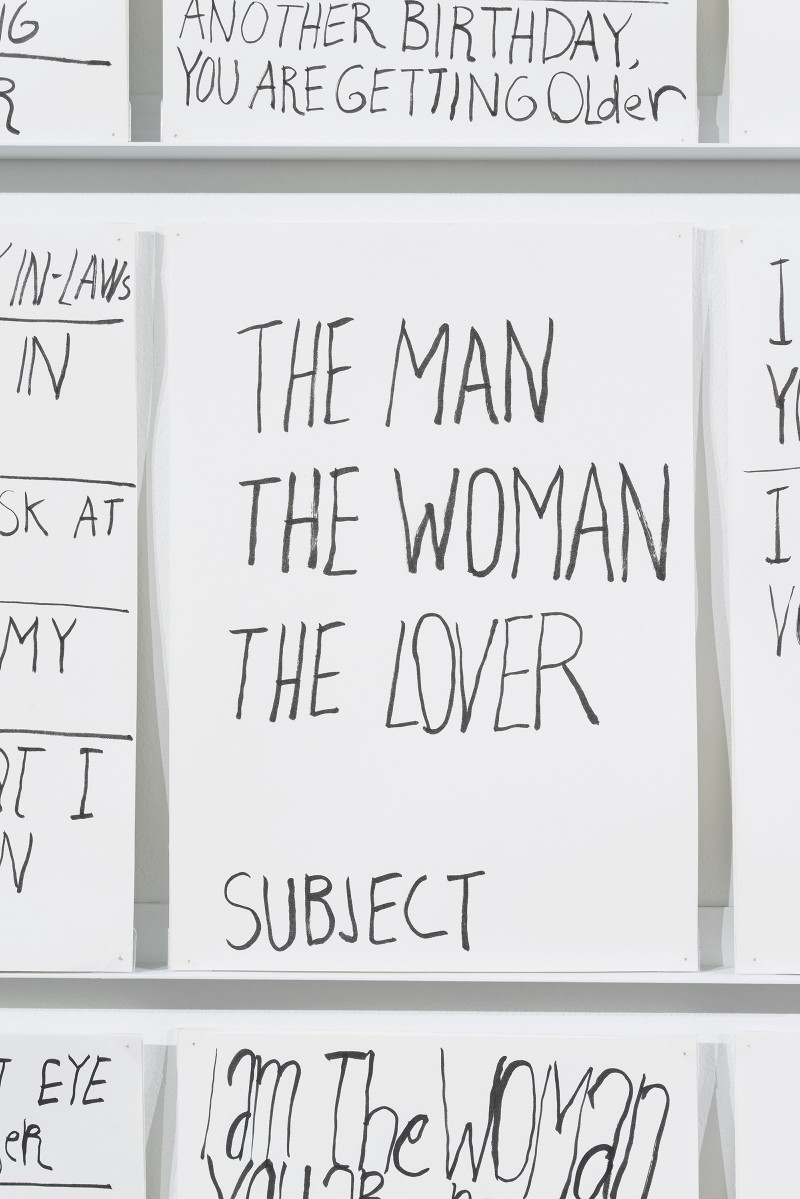

These two “drives” are absolutely pivotal to Mullican’s “The Meaning of Things”. What the artist tries to do is to show us a way of how to produce a narrative to these impulses as they circulate within the pseudo-ethereal expanse of the digital cosmos. The narrative Mullican provides, like all narratives, is fictive in its basic form. We have a title, scenarios, characters and “points of view”. These are noted down in the first 96 “pages” of the mounted work. We are not, however, given very much information. Characters are introduced in the most abstract and generic formulations: there are “lovers,” “woman,” “man,” “husband,” etc. Possible “chapters” are divided into equally generic forms: “sex,” “birth,” “death,” “actions,” etc.

There is not much of a plot in Mullican’s story. Instead, there are alphabetically ordered lists of terms of “sub-genres” of the “genres” (or “genus”). So, after the category of “sex” we have long lists of terms (mostly everyday vernacular) for genitalia, nipples, hips, and tongues. Thus, within the repetitive, ritualistic nature of constructing the images, there is another repetitive nature: the production of lists, the arduous repetitive act of notation, of the sheer reproduction of the same thing (“PENIS/SCROTUM SYNONYM—BLADE COCK CROWN DAGGER ERECTION HARDNESS HEAD,” etc.).

Strangely, the sub-genres are not more comprehensive or extensive. Mullican does not exhaust the possibilities. He opts instead to remain within a tight nexus of terms of biomechanical processes (sex, actions, pain, death, etc). This evokes a kind of “return” to the corporeal. If “The Meaning of Things” acts out a repression through repetition, it is the digital colonization of the body. The work seems to mark the impossibility of the pure existence of bodily life, a bodily life that fascinated James Joyce so much (he once referred to his novel Ulysses as “an epic of the body”).

I had a delicate impression of Joyce’s work at the exhibition. The title of Mullican’s work suggests an intellectual scale—“things” invokes a sense of “everything”—that recalls the scale of Joyce’s magnum opus. Moreover, there is a similarity in artistic orientation toward “big issues” such as sex, death, and birth. Mullican’s work, however, gestures to the existence of a disturbance that underpins life, a kind of incurable Weltschmerz (“world-pain”—a theme developed by Freud in his 1930 work Civilization and Its Discontents). This is signaled in what I take to be the parenthetical subtitle of the work: “(who feels the most pain?)”. The poignant starkness suggested in the subtitle also gives some sense to the bluntness of the text pieces that precede the images.

To and fro between the virtual and real

Strikingly, the closing parenthetical mark formally cuts across the question mark in the subtitle, making it look like the parenthetical remark was intended to correct, or annul, its syntactical function. This causes an ambiguity in the declaration of the question, one that short-circuits the assumption that a question always presupposes an addressee. Mullican converts the question into a harrowing maxim—to grasp the “meaning of things” comes at the price of “feeling the most pain”.

With this declared pain, there is a sense that what was once referred to as “postmodern art” is over and what we are left with is the terror of what to make of a world that cannot differentiated between images that depict horrendous acts of violence (images, for example, of executions) and images that depict those same acts of violence in simulated form (by makeup artists in movies, for example).

In trying to make sense of them in the construction of a fiction, Mullican seems to suggest that the presentation of the dissolution of the indifference between images—leading to an inert declaration that the “real is virtual” and the “virtual is real”—is simply not enough. Rather, we need to render more precise what is at stake in the ostensibly infinite oscillation from real to virtual, an oscillation that is simultaneously underscored and challenged in Mullican’s images.

Mullican deftly challenges this simple to-and-froing of “virtual” and “real” by suspending the idea that only through the material/physical printing out of the digital images, the content of the images is “restored” back into the “real”. It is important to note that these are works housed in the gallery space, that is, in an “abstract” space (as a space in which the outside world is brought to a standstill and we can think about what is presented before us). This means that it is the ideal location in which to present an abstraction like fiction.

Hypnosis as artistic escape

This brings me to my last point. The “wealth” of images that circulate in the digital ether calls for nothing less than an expansion of curatorial practice. The artist is no longer the producer of unique images signed under the authority of his name. Rather, the artist is the custodian of images already circulating, already permeating the cultural psyche. In the context of the superabundance of material, the artist is forced into curatorial work. The artist has to curate all the material that is produced on the Internet and in everyday life. This is how an artist produces new work.

But what does hypnosis do to curatorial practice? What is Mullican trying to remember? I think that Mullican’s “The Meaning of Things” escapes the real problem of the everyday experiences that complicate digital procedures by reverting into the state of hypnosis (even if it is only implied). I would be curious to see in what way the artist would explore the relation between hypnosis as a mechanism of the remembrance of a past that is not related to the present (which is how Freud understood it, at least according to my understanding), and the ubiquity of digital imaging.

Without a more focused exploration of this point, I fear that the work will simply be re-ingested into the normal ways of image production since the memory-work that the hypnosis is trying to do ends up reducing remembrance to a very simple thing. For Freud, hypnotic remembrance keeps the past (the situation in which memories originally form) totally cut off from the present (the situation in which the patient suffers “the most pain”).

In any event, there is a complexity to Mullican’s work that is very interesting. I have only tried to give some impression of it by concentrating on what I took to be the exhibition’s most provocative and poignant work. The curatorial team at the Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery has done an excellent job in show-casing Mullican’s work in its complexity. This means that they have refused to elude the intellectual difficulties we face when confronted with them. I found this to be a brave maneuver, one that is greatly appreciated.

—Anda Smithson is a writer living in the Hudson River Valley. She received a bachelors degree in Art History from Vassar College.

Matt Mullican at Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery is on view from Jan. 19—Feb. 26, 2016. Gallery hours are Monday – Friday: 10 am – 5 pm, and Saturday – Sunday: 12 pm – 5 pm.