This year marks the 88th Academy Awards and the 84th year that animated shorts have been a part of the show. The 2016 crop of five nominees was shown in theaters across the country in a pre-packaged, 90-minute program for one week only, ending Feb. 11. The films range anywhere from six to 17 minutes in length.

All of the nominees are wildly different from each other in style and plot, and yet a tenor of bleakness and grief seems to perfuse most of these films. A small ray of light is offered by Pixar’s entry, and yet it is too little too late (or maybe too little too early, as it was the first nominee shown in the viewing I saw).

Timeless but tiresome

In his directorial debut, Pixar animator Sanjay Patel brings a “mostly true” story of his own childhood alive in “Sanjay’s Super Team”. When forced to turn off his Saturday morning superhero cartoons and pray with his Hindu father, young Sanjay enters a “Matrix”-esque daydream, fighting a tormented spirit alongside a superhero team of Hindu gods. Although Sanjay’s father is initially disappointed by his son’s apparent lack of interest in his culture, Sanjay surprises him at the end with an adorably crude drawing of the Hindu gods in typical superhero garb—Sanjay’s Super Team.

While the film is thematically timeless and touching, it is stylistically tiresome. The bulbous heads and saucer-like eyes of Sanjay and his father are disappointingly cartoonish, a style Disney/Pixar has been maligned for but seemed to be making strides to correct in the studio’s Oscar-nominated hit, “Inside Out”. The fight sequence, while being an inventive depiction of the convergence of Western and Eastern culture, feels contrived and redundant. Pixar is well-known and well-loved for mastering the art of making films that are fresh and heartfelt. Unfortunately, “Sanjay’s Super Team” can only get marks for one of those qualities.

“Super Team” is not the only entry designed to tug at the heartstrings. Chilean newcomer Gabriel Osorio’s “Bear Story” touched hearts and won awards around the world before stepping into the Oscar ring.

In a softly lit and pristine city, an anthropomorphic bear rendered in crisp 3D animation rings a bell on a street corner, enticing young cubs to look into a diorama of his design. The diorama reveals the bear’s terrible story of his abduction from his perfect life, his imprisonment in a circus, the loss of his family and his grief. Based on Osorio’s own family history, “Bear Story” is a clever allegory for the devastation wrought by the Pinochet regime in 1970’s Chile.

Still, something about its sweetness leaves a sour taste in the mouth. While the animation is top-notch, the story feels cloying and at times flippant (in one scene, the circus kidnappers enter the apartment of a giraffe only to find they must go up to the next floor of his two-floor, ceiling-less apartment to bonk him on the head and abduct him. Ha ha). The insistence on a bright color palette, dulcet music, and the overall “feel-good” ending, despite leaving bigger questions about the “disappeared” unanswered, lessens the overall effect. What this short needed was grit; instead, it was pure syrup.

Greek gore and fear of the future

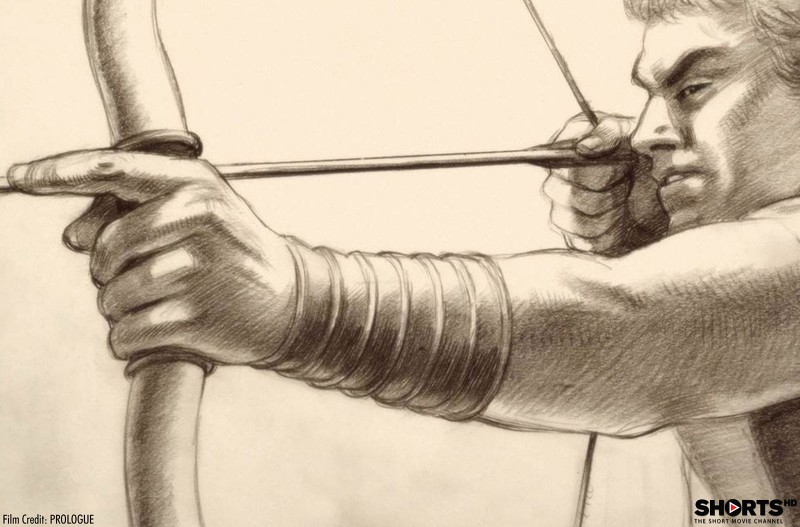

Internationally acclaimed animator and three-time Oscar winner Richard Williams’ “Prologue” has the exact opposite problem. It’s downright gruesome (the short comes with a warning to parents to leave with children due to graphic violence and nudity). A simple and nearly silent story of battle between Athenians and Spartans ends in a bloodbath. A young girl encounters the carnage and runs to the arms of her grandmother, her wispy screams and cries echoing Williams’ deft artistic touch. The photorealistic short is animated entirely in color pencil on a blank background of creamy sketch paper, leaving the world Williams creates undefined.

“Prologue” is arguably the most artful of the five shorts, clearly showing that Williams’ skill has not deteriorated with age (he is 82). Visually, it is astounding. And yet it fails critically as a story with a beginning, middle, and end. It is less a short film and more a trailer for an as-yet-to-be-made feature. This, coupled with the horrific acts of battle field violence (including a homoerotic sword thrust to the buttocks—appropriate for a Greek battle, I suppose) leaves the viewer feeling sickened and unfulfilled.

Two shorts that were in the program are also available to stream right now: “World of Tomorrow” and “We Can’t Live Without Cosmos”.

“World of Tomorrow,” directed by festival darling Don Hertzfeldt, is a grimly prophetic tale of man’s folly in his quest to live forever. The plot is incredibly simple: A toddler named Emily is contacted by her third generation clone from several hundred years into the future. Together, clone-Emily and Emily-prime examine the future, a time riddled with futility, inhumanity, and fear of impending death by asteroid. Hertzfeldt’s iconic, cartoonish stick-figure minimalism provides an intriguing contrast to a sci-fi story of technology gone amok. While the crude style serves to underscore the bizarreness and absurdity of this technologically saturated world, it renders portions of the film intended to be sentimental or harrowing flat. For example, Emily-three explains that the “shooting stars” the two of them watch are actually dead bodies careening to Earth from outer space, lower-class people who attempted to escape the imminent asteroid strike through shoddy time travel. What could have been a disquieting display of vivid color and glaring light is merely repetitious streaks of yellow. Still, the films does a marvelous job of discussing contemporary fears of hasty technological development and its potentially meaningless and inhuman consequences in the future. “World of Tomorrow” is currently available on Netflix.

“We Can’t Live Without Cosmos” comes from Russian director Konstantin Bronzit. The story revolves around two lifelong friends and astronaut trainees. When one of them dies in his premier space mission, the surviving friend slips into an intractable depression. Although it is not explicitly shown, it is heavily implied that the friends are reunited through suicide. Another short done in a simpler, hand-drawn style, “We Can’t Live Without Cosmos” is entirely without dialogue—a clever mimicry of the silence of outer space. Instead, a poignant piano melody acts as the voice of the film. “We Can’t Live Without Cosmos” reaches the emotional heights that “Bear Story” aspires to but fell short of because it did not respect the inherent tragedy of its story. “We Can’t Live Without Cosmos” is streaming now at The New Yorker’s Screening Room.

Certainly these films are not representative of the wider world of present-day animation—Disney, Dreamworks and Studio Ghibli, monoliths of optimistic children’s entertainment, can attest to that. But, they do present an interesting question: can animation transition to the world of adult films? Richard Williams is planning on extending “Prologue” to a feature-length film—could it sell? Could a feature-length Hertzfeld film sell (not counting “It’s Such a Beautiful Day”)? The recent success of “Deadpool,” the first R-rated superhero film, speaks to the power of niche audiences. And, with the advent of increasingly popular streaming services like Netflix, Hertzfeld, Williams, and other animators may have stumbled on a new platform to promote their works. Consumption of entertainment is changing. Perhaps animation is the next big trend.