The works in Jayson Musson’s The Truth in the Song are beautiful in execution and serious in purpose, but they are animated by an impish spirit of subversion. In his first solo show at Fleisher-Ollman Gallery since 2012, Musson explores the painterly possibilities of the Coogi sweater. As someone who grew up in the eighties, Coogi sweaters conjure up memories of the benignly paternalistic Bill Cosby from The Cosby Show–memories which now seem unsettling given recent allegations about his predatory behavior. Musson takes on the complex cultural meanings of these sweaters, as well as their expressive and visual potential. The canvases in The Truth in the Song prompt reflection on popular culture, commodity and identity, but what I found most compelling about Musson’s Coogi paintings is their profound yet playful engagement with art-historical references. Musson knows where he comes from, both as an artist and an individual.

Color and song

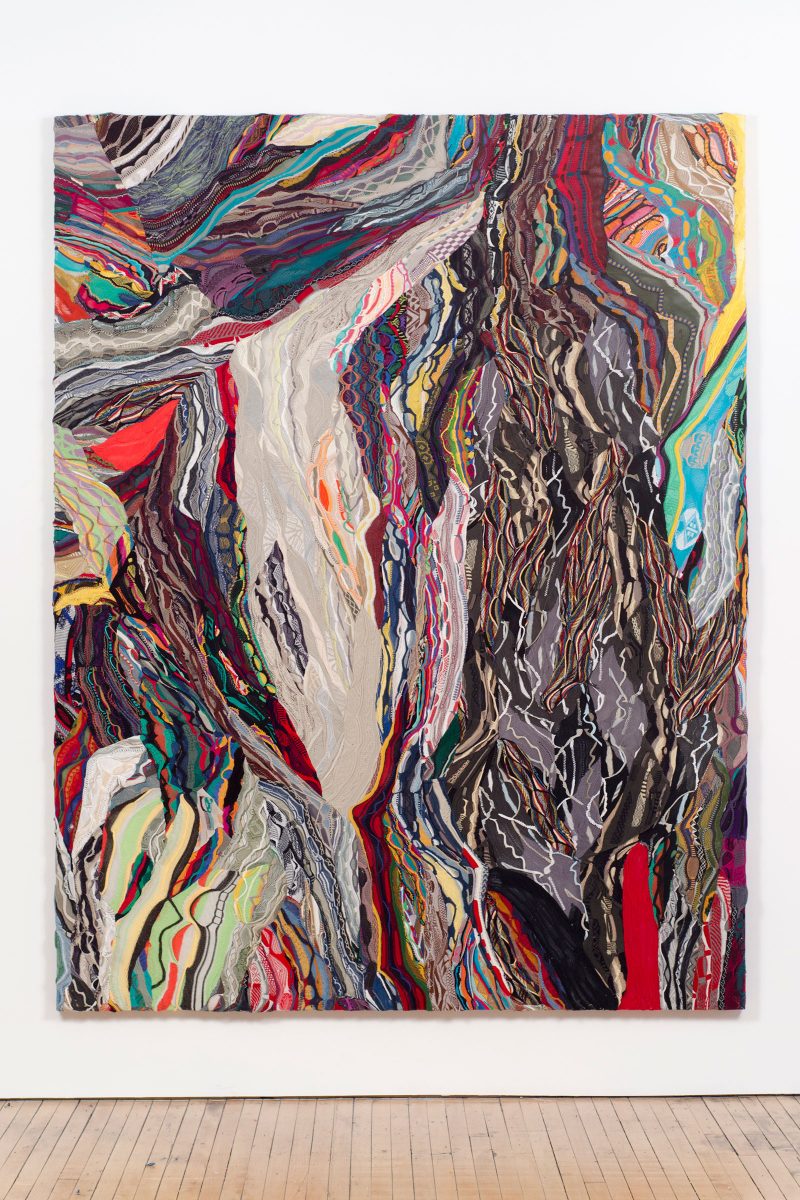

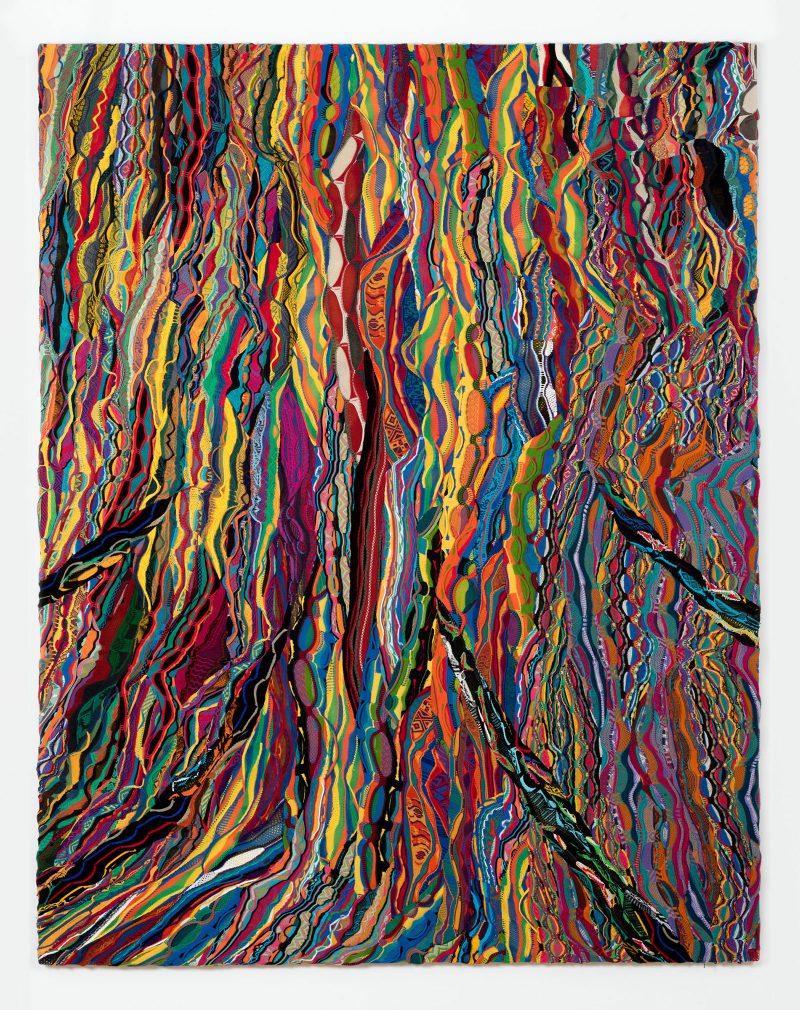

Entering the brightly lit gallery, I was struck by the vivid contrast between the austere white walls and the brilliantly colored Coogi paintings. Musson is not afraid of color, and he uses it to great effect. These paintings are assembled like collages of cloth, consisting of fragments of multiple sweaters that Musson has collected, stitched together to form a single composition. The Coogi collages are then stretched and stapled to the wooden frame of the canvas. If needed, Musson goes in and stitches individual pieces which may have split in the process of stretching. Apparently, he stretched about half of the canvases of The Truth in the Song on site a few days before the show opened, suggesting that the final assembly is but one phase of a larger, deeper process in making these Coogi paintings.

On the far wall of the gallery is “Two Pillars of Ivory,” whose title may be a reference to a lyric from the song “4th Chamber,” from an album by Genius/GZA of the Wu Tang Clan. These musical references come as no surprise, given that Musson was a member of the Philadelphia-based group Plastic Little, begun in 2001. In the “4th Chamber,” a speaker sings of judging wisely, lounging between two pillars of ivory, evoking the Biblical figure of Solomon in his palace. The language also evokes the description of the body of the beloved in the Biblical Song of Songs, attributed to Solomon himself. Given that these Coogi sweaters were meant to be worn, reference to the physical body comes into play. The pale shape that stands out within the colorful composition appears almost like a body in motion, like Marcel Duchamp’s classic Modernist painting at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2” (1912). The whiteness of the body-like shape in the Coogi painting is no accident–the histories of Modernism, Primitivism and colonialism are deeply entwined, and artists like Duchamp and Picasso exploited the so-called primitive, racialized bodies of the Other in their work. Musson plays with these references, transforming and subverting them through medium and context.

Sweater sound collage

Several of the Coogi paintings overflow the confines of their wooden frames, spilling over in waves of cloth that become almost sculptural. His canvas “Pygmalion VII” is aptly named given this sculptural context–Pygmalion was the sculptor made famous in Ovid’s Metamorphoses for carving an ivory statue of a woman that was so beautiful he fell in love with it. The goddess Aphrodite then caused the statue to come to life. In a more modern context, the story of Pygmalion was adapted by George Bernard Shaw, whose play served as the basis of the musical “My Fair Lady,” about Eliza Doolittle, a low-class young woman transformed into the perfect upper-class lady through elocution lessons from Henry Higgins. The Shavian sense of upsetting class (and society’s) mores is vividly conveyed in this Coogi painting through the use of two distinct sweaters, which differ from each other in terms of color and directionality. Musson drapes one piece of cloth perpendicular to the rigid, stapled cloth on the canvas, suggesting layers of identity, like layers of skin, that conflict with one another. Are we looking at Henry Higgins, the scientist committed to his social experiment, or his creation, the independent Eliza Doolittle? These questions of identity remain open ended.

Like Romare Bearden’s collages, Musson brings together a spirit of formal experimentation with a deep-rooted cultural awareness. The title of his canvas “Knowledge God” may refer to the 1995 song of the same name by Raekwon, of the Wu Tang Clan. The repeated patterns of the Coogi fragments echo like musical phrases across the canvas, creating a sort of sweater sound collage. Just as Bearden’s collages often evoke sense of communal ritual (as in his series, “The Prevalence of Ritual”), Musson draws on shared reference points that span high-brow to low-brow to create visually arresting and thought-provoking work.

While Musson is best known for his YouTube persona, Hennessy Youngman, a hip-hop art historian who lampoons the art world in a series of hilarious and no-holds-barred videos, it would be a mistake to understand his work as purely flippant and irreverent. Together with the swagger and the humor is a deep knowledge of art history and a real seriousness of purpose that come through in these Coogi paintings. Musson takes this important artifact of African-American culture and unravels it, piecing it back together in his own way.

The Truth in the Song is on view at Fleisher-Ollman Gallery, 1216 Arch St., 5A, Philadelphia, PA, until May 28. Open Tuesday–Friday, 10:30–5:30 and Saturday 12–5.