Robert Irwin is a magician. He doesn’t pull rabbits from hats and has no cards up his sleeve. Rather, he’s like the magician in children’s stories who waves a wand–and if you are willing to accept his spell, you will never see in the same way again. “Robert Irwin: All the Rules Will Change,” at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden through September 5 and not traveling, investigates the beginning of his career when, as a young artist emerging in the shadow of Abstract Expressionism, he had to re-invent painting for himself.

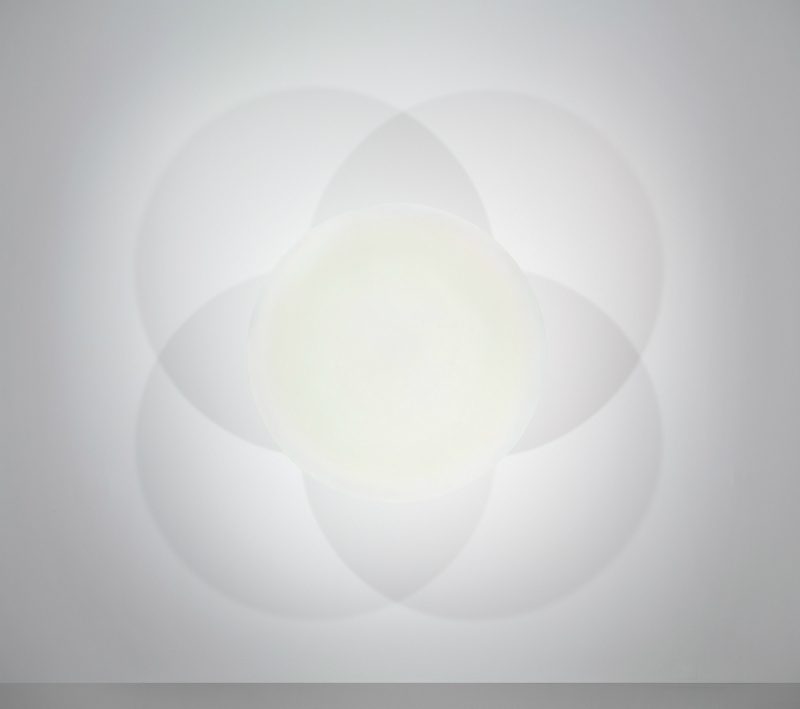

A major figure among a group of Southern Californians who have been called Light and Space artists, Robert Irwin is a constant questioner who always tries to get to underlying principles–and then questions them. His career has involved a series of questions that, once solved to his satisfaction, have led him to further questions, and have led his work into unanticipated areas. In 1970 he gave up painting, closed his studio, and began a trip into the unknown. That journey resulted in four decades of conversations, lectures–wherever he was asked–and site-specific indoor and outdoor installations of various sorts–some permanent, some ephemeral, and a number of them unrealized. He has often been brought in when the situations were difficult–topographically, socially, and/or bureaucratically. He created a garden for the Getty Foundation at their campus on a hill overlooking Los Angeles; at an abandoned factory in Beacon, NY, which the DIA Foundation turned into a museum, Irwin designed the interiors as well as exterior public spaces, including that characteristic contemporary approach to most buildings, the parking lot.

Painting as object

The Hirshhorn’s exhibition charts Irwin’s exploration of the formal concerns of abstract painting during the late 1950s to early 1970s–the relationship between figure and ground, the expressive possibilities of paint, color relationships, and the implication of color for spatial relationships. He realized that once modern painters rejected the idea that a painting was an illusory window onto space behind the picture plane, they didn’t need the fiction that paintings themselves had no spatial dimensions. Paintings are objects.

During 1958–60 Irwin made a group of 20” x 20” paintings for which he crafted beautiful wooden frames. They were intended to be held in the hand–experienced by touch as well as by sight. When he moved on to large paintings hung conventionally on the wall, he became more and more interested in his peripheral vision, in the painting’s relationship to the wall and the lighting by which it is seen. He experimented with curved surfaces, which blurred boundaries between the space suggested by the paintwork and the actual space occupied by the painting. He then cantilevered paintings with curved surfaces from the wall and arranged lighting to cast shadows that were as integral to the works as the painted surfaces. He ultimately realized that he could manipulate light and space without the painting–and this is where his career as a painter stopped.

Under Irwin’s spell

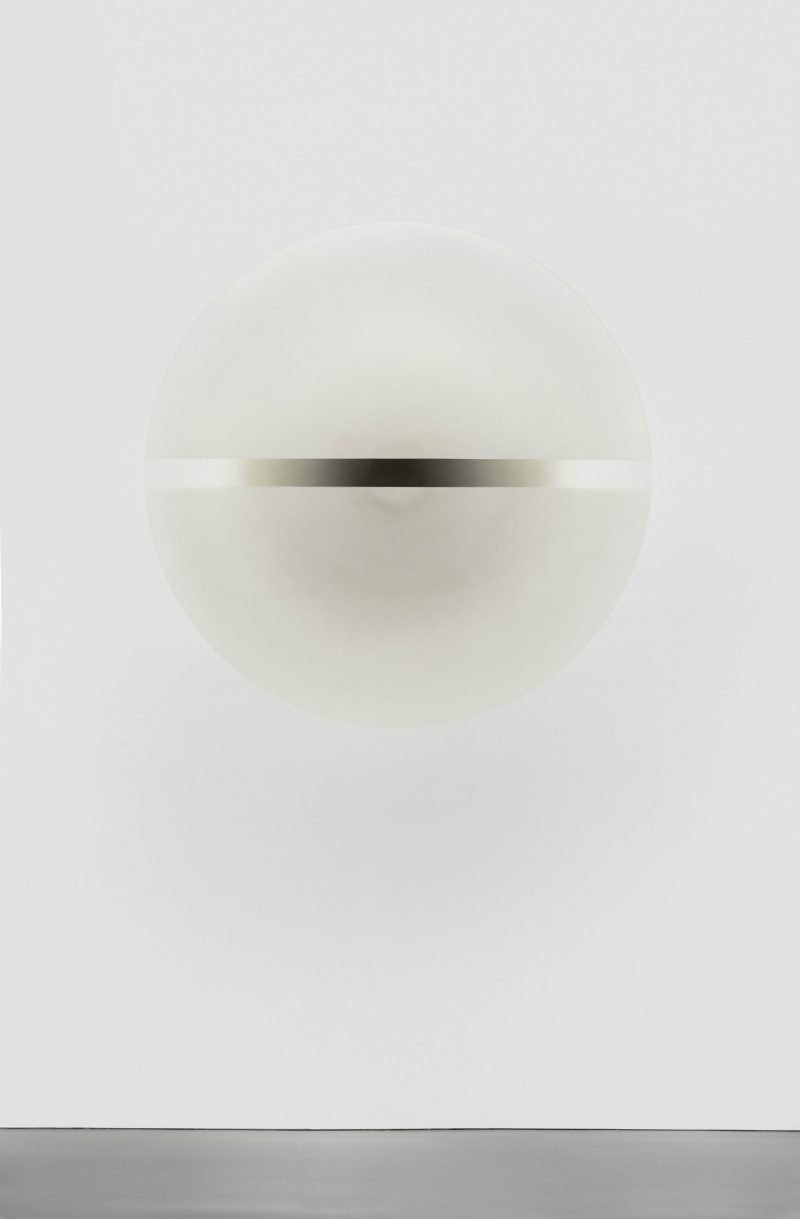

The curators wisely began the exhibition out of chronological order, which they otherwise followed, with work done from 1958–69, plus a large final installation which the artist created as a response to the Hirshhorn’s unusual, doughnut-shaped plan. The first painting visitors encounter is one of the seductive works from 1969, on a shaped, circular piece of acrylic which is positioned away from the wall.

I had the wonderful experience of taking a dozen college classmates and their spouses through the exhibition recently. Only one person had any background in art history and none of them recognized the artist’s name. I explained that Irwin’s work takes time–literally, time for the eyes to adjust. They concentrated on the floating sphere bisected by a dark, horizontal line which disappears towards the circle’s margins–and the magic began. The painting creates a series of changing optical effects which it would be useless to try to explain, and because the effects depend upon presence and time, the artist refused to have his work photographed for many years–he has since relented. Anyone who knows Robert Irwin’s work only from reproductions has no idea of what the work is about.

Several rooms down, a woman on my tour said she had entered the room and looked back to study the reverse of the wall she had just passed. It took her a while to realize that she had not been looking at the artist’s work, but had been giving serious attention to the wall itself and the corner of the gallery. She was under Irwin’s spell, indeed, the spell that he would like to cast on all his viewers–the realization that there are visual phenomena around us which we routinely crop as we concentrate on what we were already looking for. Our ability to name things limits our attention to anything beyond those things. This is indicated in the title of Lawrence Weschler’s wonderful journal of 30 years of conversation with Irwin: “Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing one Sees.”

I encouraged everyone to look behind the artworks, beginning with the floating sphere and ending with the Hirshhorn installation, to see how Irwin achieved his effects; they found nothing up his sleeve. In the case of the sphere, he projected a simple tube of acrylic from the wall, to which he attached the spherical form. The installation in the museum was created with plywood to which he stapled scrim–a translucent fabric used for stage sets that has become one of Irwin’s favorite materials. These mundane materials and the way the artist uses them are not very interesting. No, that’s not true–conservators who studied his work contributed an essay to the Hirshhorn catalog, and the Getty Conservation Institute has recently published a monograph on the materials of the Light and Space artists. To be more accurate, Robert Irwin’s materials are not very interesting for general viewers because they are not where his art lies. Rather, it is his vision which transforms humble materials as well as everyday life into magical experiences, and it is that ability to see which he offers to us.

“Robert Irwin: All the Rules Will Change,” a major exhibition by one of the leading postwar American artists, runs April 7–Sept. 5, 2016 at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.