Beyond the show’s title, which made me think of the polarizing rhetoric that divides people into “us” and “them,” Our America, is an excellent 70-artist exhibit. The traveling show of works from the Smithsonian American Art Museum closed recently at the Delaware Art Museum (and opens at the Allentown Art Museum on June 24). I’m truly glad I got to see it.

The curated show of paintings, sculpture, video and works on paper from the 1950s to the present is notable for works with fierce pride in Latino identity and for works with unabashed political underpinnings. The exhibit and its catalog shed light on contemporary artists who would stand out in any group.

At the Delaware Museum, the show sprawled down a hallway, into a small chamber and then down the stairs into a large space with some partition walls. And within each space the pairings made sense, works grouped by idea or theme with almost everything, regardless of the stated category, fitting into a broader overarching theme of “identity.”

Local angle

What drew me to Wilmington especially were the artists whose names I knew and whose works I love – Pepón Osorio, Adál Maldonado, Miguel Luciano, Margarita Cabrera, Carmen Lomas-Garza, Enrique Chagoya, Rafael Ferrer. Many of them have shown work in Philadelphia, in venues from Swarthmore College to Temple Contemporary, and especially, at Taller Puertorriqueño, which consistently serves up exhibitions that demonstrate that they have their finger on the pulse of contemporary Latino art.

I am going to highlight a few of the many excellent works in the show, but note, this exhibit is an art omnivore’s feast with something for any art lover.

Politically-charged works grouped together

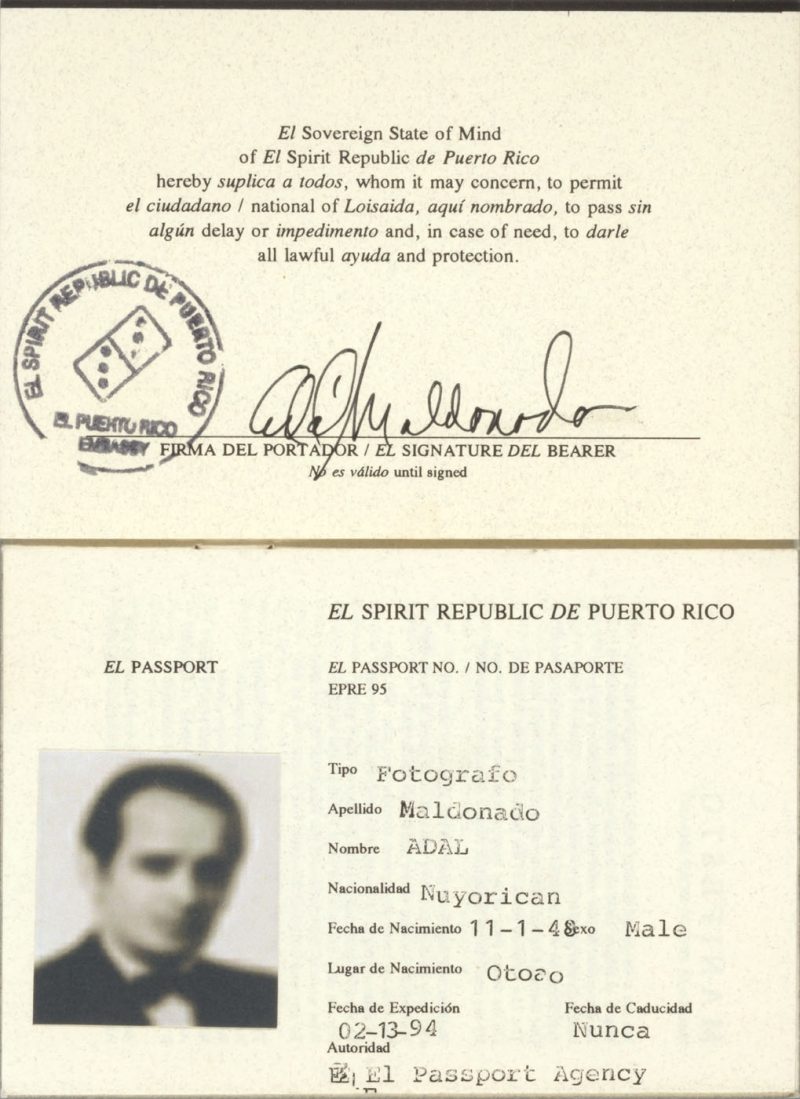

I saw Adál Maldonado’s works at Taller Puertorriqueño in 2004, and the mischievous conceptual sculpture, print and video pieces touched my funny bone and stabbed me with a pang of sorrow. In his “El Spirit Republic de Puerto Rico” (1994), included in Our America, Adál creates documentation, placed in glass vitrines, of a parallel universe in which Puerto Rican astronauts (Coconauts) are the first to reach outer space and passports have I.D. photos that are a complete blur, since blurriness is the state of being Puerto Rican in America, according to the artist.

While gently poking fun at the perceived notion that nothing happens on the sleepy island of Puerto Rico (or indeed for Puerto Ricans off the island), Adál’s work also expresses a longing for recognition and respect, which is heartfelt and poignant. I loved the work in 2004, and in this strong group show it is a standout.

In the Delaware Museum’s installation, Adál’s work was grouped with other highly-charged works in a small side gallery. The additive effect of viewing piece after piece in the room was electric – like stepping into a kind of special place for whole-truth telling, where some of the truth tellers are comedians and some are scholars of history.

Ken Gonzales-Day’s photo-postcards, “Erased Lynchings,” (2006) are 15 small inkjet prints based on antique postcards from the 1850s onward of so-called cowboy justice in California. These postcard photos of lynchings are not figments of Gonzales-Day’s imagination. He unearthed 350 original postcards, which for this project, he digitally altered, erasing the lynched man, leaving only the witness/perpetrators. As chilling as the work is to see, it is devastating to think about how this American history has been erased.

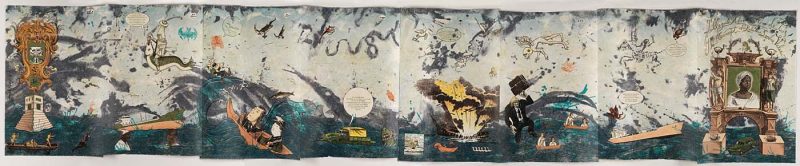

It’s the opposite of erasure in Enrique Chagoya’s financial history scroll print, “Illegal Alien’s Guide to the Concept of Relative Surplus Value” (2009). Set out flat in a vitrine, the 15” x 80” lithograph reads like a visual narrative of the financial universe ala Monty Python’s sketch comedy hour. A sea-faring narrative bracketed by a Mayan temple on the left and an altar to a slave on the right, the scroll brings art history, history, pop culture and Karl Marx together to savage the world financial meltdown in 2008. Olive Oyl yells to Popeye for help; an oil tanker spews oil blackening the sea; a Hokusai wave threatens a rowboat, dragons and fish fly, bomb-carrying storks explode the ships below, and throughout, thought bubbles quote Karl Marx – “Nothing can have an intrinsic value. The value of a thing is just as much as it will bring,” says a dragon. It’s a rollicking piece and deserves to be studied.

Photographs by two women stand out

Also deserving of study, especially for those who will never go to the real place, are the landscapes of Delilah Montoya, broad sweeping vistas of depopulated Arizona near the border with Mexico. The beautiful works are sly though, serving up, on close inspection, the details that make them more than landscape photos. In “Humane Borders Water Station” (2004) mountains in the background and a brooding, storm-cloud sky hold your interest until you zero in on the 3 barrels by the side of the road in the middle distance with the flag pole and ad hoc flag (looks like a t-shirt) flying high beside them. The photo documents a non-profit organization’s efforts to prevent migrants from dying of thirst as they cross the border. It’s a chilling reminder of the hardships people face as they seek a better life.

Embroidering on a personal history in a series of mostly black and white photos, Christina Fernandez re-enacts the role of Maria Gonzalez, her great-grandmother, who was the first in her family to come to the US from Mexico (around 1910). “Maria’s Great Expedition” (1995-96) shows Fernandez dressed as Maria, with hair, clothes, house and environment seemingly authentic to her ancestor’s dates and story. But the story-telling portraits conflate the personal with the history of the time to reflect composites that are perhaps as historically accurate as any history, whether family or “official.” “Maria’s Great Expedition” owes a debt to Cindy Sherman, who has always appeared – dressed up – in her fantasy and history-tweaking works. But Fernandez’s works have a freshness and intimacy to them that invites thoughts of your own family’s scrapbooks, and stories about their arrival in this country.

Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Latino Initiatives Pool and the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquisition Program © 1988, Pepón Osorio

While Pepon Osorio is known very well nowadays for his work in the community, it is great to be reminded that he is also a fine found-object sculptor. Osorio’s “El Chandelier” (1988) is a tweaked functioning crystal chandelier festooned with tiny decorative plastic tchotchkes like you might find on a car dashboard or in a piñata. Miniature dice, statues of saints, cute animals, beads, fringe, dolls, soccer balls, airplanes. The piece – hung from the ceiling — is colorful, rococo, beautiful and more than a little out of control in a controlled way. It embodies the desire for beauty and “stuff” that all of us have and that Osorio saw then all around him in the Puerto Rican community.

African and Taino identity in the exhibition

Other memorable appearances in this terrific show are Miguel Luciano’s “Pure Plantainum” (2006), a platinum-plated green plantain sitting on a black velvet pillow in a glass vitrine; Margarita Cabrera’s soft stitched and droopy “Black and White Toaster,” (2011) “Brown Blender” (20110 and “White Coffee Maker” (2011) whose hairy threads left uncut and swirling around the pieces suggest the long hair of the female factory workers making actual small appliances in the maquiladoras in Mexico across from the US-Mexico border; and Carmen Lomas Garza’s beautiful gouache on paper drawing, “Camas para Suenos” (1985), a scene of a mother inside the house making the beds while two kids sit on the roof looking at the moon.

Marcos Dimas’s “Pariah” (1971-72), a monumental oil on canvas of an androgynous person whose smile and gaze approximates Mona Lisa but whose sunburnt colors and sensual brush strokes, dots and paint drips put this in the land of magical realism. The show’s catalog points out that Dimas at the time was an activist for Puerto Rican empowerment and identity in its African and Taino (native) roots. The piece is truly empowered and even if it wasn’t one of the largest paintings in the show, the fierceness of the portrait makes you stand at attention.

More about the exhibition

As a showpiece for what the Smithsonian has been collecting and as a relatively comprehensive look at Latino art from the middle of the 20th Century onward, Our America, featuring artists of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Dominican descent, is a great reminder of the breadth and depth of the art world and of how works by artists of color or whose ethnicity is not WASP get wrongly edited out of what we think of as “the art scene.” The massive, 367-page catalog with full color plates of work in the show and scholarly essays by E. Carmen Ramos of the Smithsonian and Tomas Ybarra-Frausto a guest scholar, is a wonderful companion and archive of the show. Not only do the essays grapple with the label “Latino art,” but each artist gets a short but in-depth write up on their work.

Our America opens at Allentown Art Museum in Allentown, PA (June 24 – October 2, 2016); Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg in St. Petersburg, FL (October 28, 2016 – January 21, 2017); and the Hunter Museum of American Art in Chattanooga, Tenn. (February 17 – June 4, 2017).