László Moholy-Nagy is included under many headings in the history of 20th-century modernism: in photography, where he was a pioneer and master of the photogram and an important experimental photographer; under experiments with light for “Light Prop for an Electric Stage,” a construction made from aluminum, steel, glass, wood and plastic which casts changing shadows on the surrounding space as it rotates–the same effect produced by disco balls; under painting and cross-referenced under conceptual art for “Construction in Enamel,” an image in three different sizes–Moholy claimed to have ordered the abstract, geometric series by telephone from a commercial sign shop; under collage, for a significant body of work; under art and design education since he taught the foundation course and ran the metals workshop at the Bauhaus, and founded the New Bauhaus in Chicago; under writer for important books on photography and art pedagogy; under graphic design and typography, for designs for letterhead at the Bauhaus in Weimer, Dessau, and Chicago, and designs for a major series of monographs, Bauhaus Books (Bauhausbücher); and, of course, under Hungarian Modernism. I could go on.

“László Moholy-Nagy: Future Present” at the Guggenheim through Sept. 7, then traveling to Chicago and L.A., does an outstanding job of presenting this fascinating and multi-faceted man; I highly recommend it to artists, designers, and anyone interested in the history of modernism. That said, its 300 works are at least twice as many as needed; I spent three hours in the exhibition and didn’t stop for any of the films longer than ten minutes, nor did I truly study anything on display. This gigantism–unfortunately common today–encourages visitors either to move through the exhibition at an aerobic pace, or abandon it part of the way through; counting on multiple visits is too much to ask of all but specialists.

Constructivist shadows

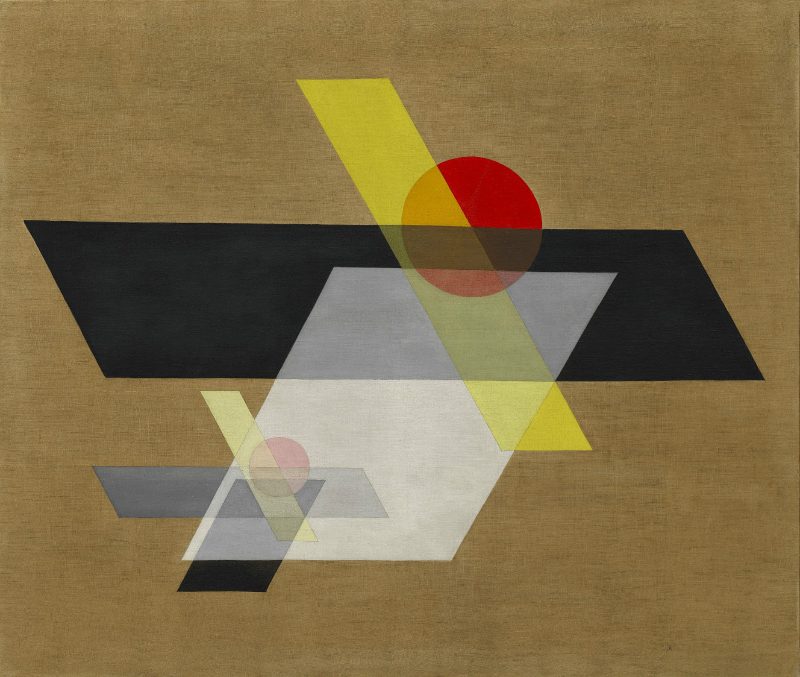

If you need to edit, I’d skip the early paintings, which are shown in abundance. They are Constructivist-influenced abstractions, some first-rate and others looking more like design exercises–but they do not offer major new ideas. Moholy’s painting gained a freedom and exuberance in the late 1930s. This may have been a result of his use of experimental materials, such as perforated sheets of aluminum, various synthetic materials including Lucite which had been distorted during manufacture, and flat pieces of Lucite mounted so that the paintwork and incising cast shadows on the wall behind them. Think of it–two-dimensional work that casts a shadow!

Unless you have a special interest you can probably skip much of the photography, because of the quality of available, printed reproductions–including the exhibition catalog. Moholy himself exhibited his collages only as photographic reproductions, and his photography in various sizes (none of which he printed himself) was reproduced in books and periodicals, depending on the circumstances. He was interested in the visual ideas and eschewed values attached to period prints and originality of editions. This stance is still contrarian.

IVAM, Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Generalitat © 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Staging Moholy’s Modernism

Moholy’s work raises many questions, some of which are more interesting than his answers, but still useful as a way of understanding how an artist works his way through visual, technical, and social challenges. He saw art as integrated with life, and it followed that artistic media should change along with new materials, such as plastics, which were developed by modern science, and that artists should work with industry to disseminate their ideas. He also worked collaboratively on many of his projects and his writing, and the curators consider his administrative work equally important to his work as an artist, designer, teacher, and writer.

Moholy made major contributions to exhibition and stage design, and in the space that protrudes from the beginning of the Guggenheim’s ramp is one of the exhibition’s highlights–a realization of an important but un-executed design, the “Room of the Present,” commissioned by the progressive director Alexander Dorner as part of his makeover of the Provincial Museum, Hannover. It was to include friezes of photo enlargements, projected films, consumer products of modern design exhibited on small pedestals held in place by filament, so they appear to float, and Moholy’s “Light Prop for an Electric Stage.” The latter is only turned on sporadically, but worth arranging time to see. The room is a particularly appropriate use of a reproduction within a museum exhibition, since Moholy and Dorner’s plan was to display enlarged photographs and industrially-produced objects–a view of the contemporary art of the 1930s that challenged the museum’s and society’s traditional emphasis on uniqueness and originality. The gallery is also incomparably easier to understand than are plans, all that survives of the commission.

“László Moholy-Nagy: Future Present” (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, L. A. County Museum of Art and Yale University Press, New Haven: 2016) ISBN 978-0-300-21479-6

Click here to see the book in the Guggenheim online shop.

The extremely handsome catalog is the one place to find a book in English that covers the range of Moholy’s very diverse career. Its eight essays include: Matthew S. Witkovsky on the significance of writing and other graphic mark-making as a medium within Moholy’s art production and administrative work, and something beyond his analytic and pedagogic texts; Stephanie D’Allesandro’s analysis of the significance of handwork to the artist, despite the fact that much of his art production involved mechanical means; Olivier Lugon looking at the significance of a series of photographs Moholy made of the 19th-century Pont Transbordeur in Marseille in relation to his friendship with the architectural historian, Sigfried Giedeon; Jennifer King discussing his exhibition designs in relationship to contested political ideas; Julie Barten, Sylvie Pénichon, and Carol Stringari on the artist’s experimentation with non-traditional art materials as a means of examining light, optics and movement; Elizabeth Siegel on the significance of teaching to Moholy and his emphasis on a broad education that integrated his students’ artistic, social, and ethical thinking, rather than a narrow focus on industrial applicability; Karole P.B. Vail surveying his lifetime exhibitions in the U.S. after his immigration in 1937; and Carol S. Eliel looking at Moholy’s continuing interest to contemporary artists including Thomas Ruff, Walead Beshty, Barbara Kasten, Jan Tichy, Olafur Eliasson and others.

The volume, thoughtfully designed by Roy Brooks of Fold Four, Inc., acknowledges Moholy’s graphic style without attempting to copy it. It is profusely illustrated and beautifully produced, and includes the first time all of his collage works have been illustrated, as well as an exhibition history, list of Moholy’s writing, selected bibliography, and index.