This article concerns the restriction of contemporary art discourse to the specificity of Philadelphia in the city’s DIY art scene. It strikes me that the focus on the geo-political and cultural particularity of Philadelphia produces a strange contradiction in how we think about contemporary art in Philadelphia. The contradiction is between the parochial fixation of trying to speak for a Philadelphia contemporary art (distinct from a contemporary art in Philadelphia) and the global status of contemporary art. In what follows I want to develop an understanding of this contradiction by paying particular attention to some interconnected issues such as the notion of contemporaneity, globality and internationalism. I close with a couple of questions, both oriented by the attempt to inquire into the very possibility of a discourse of contemporary art within the context of an explicitly regionalist focus.

Contemporary art as globalization

Contemporary art is, without question, a global phenomenon. Over the course of the last few decades, this has been made manifestly evident by the huge expansion of art biennials. Biennials are so prevalent now that to only attend the Venice Biennale amounts to a monstrous myopia. Istanbul, Shanghai, Sharjah, São Paulo, Montreal, Moscow, Jerusalem, Sydney–cities are marked by an international art fair. Indeed, I’m tempted to say that holding a biennial is required in order to procure the illustrious title of ‘major global city’ (one wonders when Philadelphia will have its own).

Two things are worth underscoring here. First, the biennial is the most dominant mode of presenting and recognizing the globalized character of contemporary art. Second, its expansionism is a direct result of the globalized expansion of capitalist markets. The movement of trade by trans-national corporations has produced a sense that the world is not a finite entity in which things are contained but, rather, is a network of endless communicational, economic, social and informational flows. It is defined by what one could call a ‘restless mobility.’

This restless mobility produced by capitalist markets renders visible the difference between ‘world’ and ‘globe.’ The former is connected to more immediately recognizable concrete realities such as the ecology, social relations, and political transformations, whereas the latter describes a certain experience of contemporary life. In other words, globalization is the condition through which we experience our surroundings and ourselves. Following from this, one could say that contemporary art is a kind of experience of globalization. More precisely, one could say that the globalization of contemporary art is the conduit through which we think about, know, and experience art.

Philadelphia’s art discourse

If contemporary art is by definition global, what are we to make of an art discourse that is motivated by addressing cultural practices in a single city or particular area? What, for example, are we to make of our discourse about art in Philadelphia? I believe that there is a certain contradiction that structures the attempt to grasp the contemporary art scene of a single place. It produces a discourse that tries to reflect on the contemporary activities of a specific area by way of a negation of the very conditions that allow you to recognize that what you are doing, saying, and thinking can be subsumed by the category ‘contemporary art.’ In other words, it tries to produce an understanding of a specific area through a globalized discourse. To have a sense of what this means, it is worth considering some concrete examples.

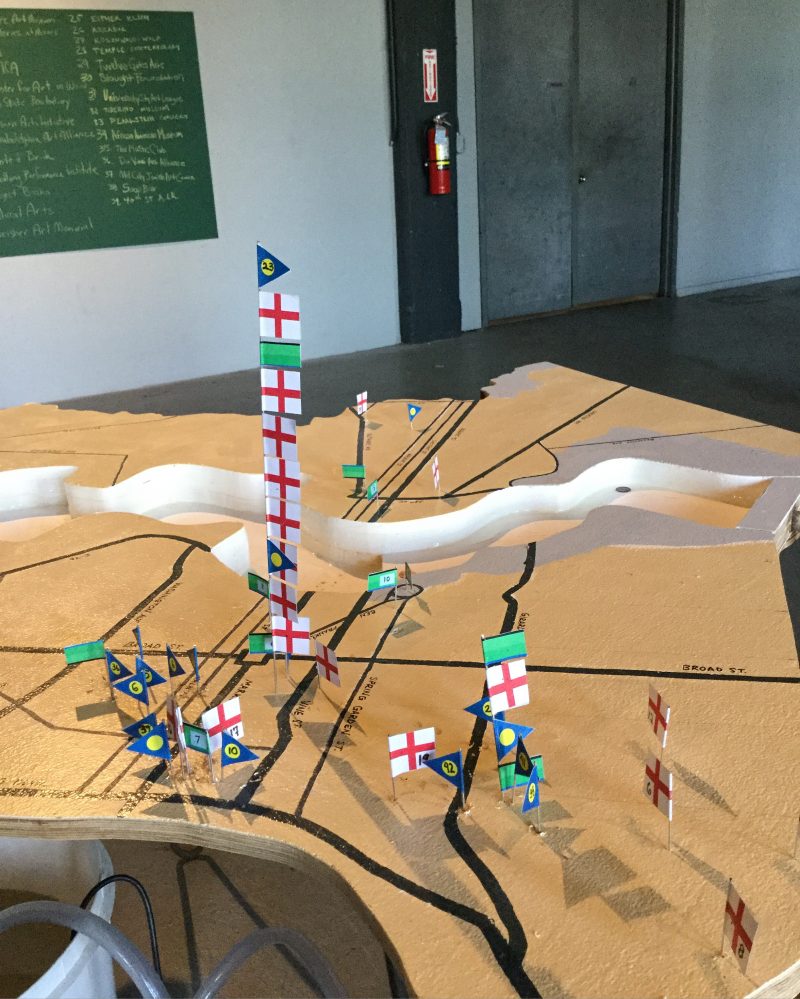

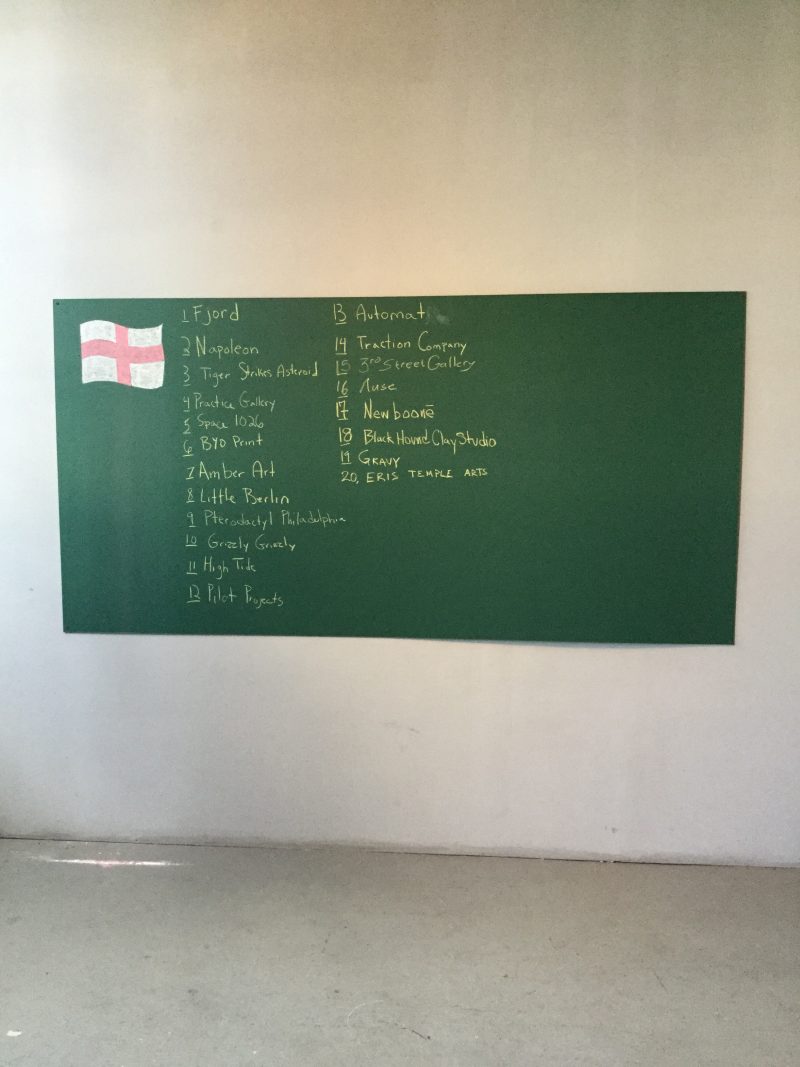

Philadelphia is said to have a vibrant, online, DIY art discourse scene–Artblog, Title Magazine, Curate This, and The St. Claire, to name perhaps the most visible, are all united by a commitment to reflecting on the cultural activities of Philadelphia. Of the four, Curate This explicitly takes up the issue of Philadelphia’s absence from any global recognition. As the general editors put it on their website, “we continually fail to show up on the international arts radar.”

There is an interesting assumption implicit in this statement. Philadelphia is already recognizable as ‘international’ in the received sense of the word. As the editors succinctly put it, “Philadelphia is the fifth largest city in the US, boasts a competitive concentration of arts institutions, and is home to a vibrant underground art scene.” In other words, Philadelphia ticks all the ‘internationalist’ boxes that identify it as a globalized hub of art. So why does it remain under the radar?

There are a number of reasons why Philadelphia remains peripheral. Uneven economic development of wealth and resources is, of course, one reason. Instead of analyzing a particular reason, I want to pursue instead the task that the editors of Curate This set themselves: “Curate This aims to solve [the] problem [of not being recognized internationally as an art center] by providing a collaborative platform for artists to define and drive the conversation about the arts in Philadelphia.” This means something quite precise–to become recognized as international, one needs to develop a discourse about oneself, a discourse that, presumably, tries to justify a place in the global art arena.

Some problems arise when considering this strategy in more depth.

A global grammar

As the editors presuppose, there are already preexisting signs that allow one to recognize the internationality of an artistic zone (art institutions, a DIY art scene, art schools, etc.). We can call this the ‘grammar’ of a city’s cultural self-identification. That is, the nuts-and-bolts of what makes a city a zone well-suited for recognition as culturally significant. Following from this, you might say that in order to be recognized as an international hub of art, the city needs to speak the language of global contemporaneity, and speak in a way that immediately registers internationalism.

If Philadelphia already speaks this common global language insofar as it shares the common grammar of international recognition, then what it lacks is a voice loud enough to be heard. If this is the case, then you could say that the problem is that Philadelphia needs to speak more loudly, not differently. This, I believe, constitutes one unconscious characteristic of art discourse that remains faithful to its own parochialism and yet has aspirations of wider recognition.

Another strategy of a parochial attitude is to continuously bear witness to one’s own activities. This is motivated by the proverbial “do-it-yourself” mentality that infects contemporary cultural production in advanced capitalist societies. The dark underside to this seemingly positive mentality is, of course, the fact that no one else will do it for you. So, if you want to put Philadelphia on the global map, you need to take charge and be its spokesperson, cultural custodian, historian, and critic. This is precisely what online forums like Artblog and Curate This do.

Philadelphia’s internationalism

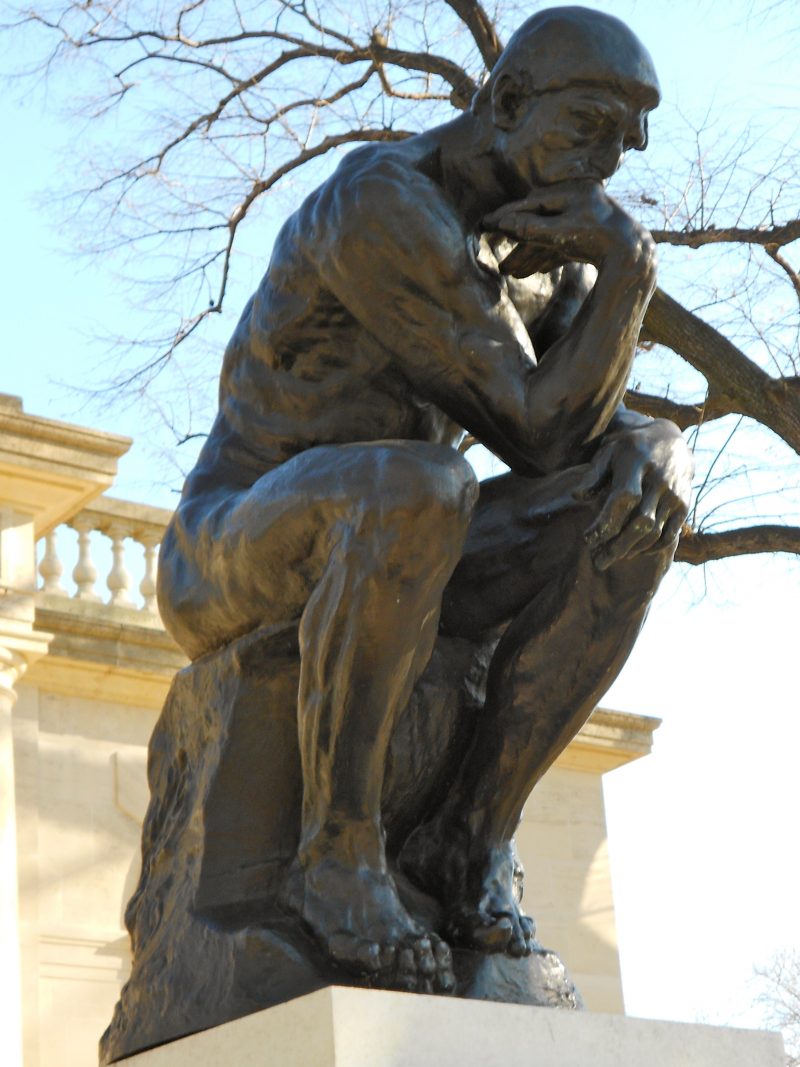

Within the context of Philadelphia, this DIY attitude finds itself in a rather peculiar predicament, one that creates a schism between its status in which exciting contemporary art takes place and its preexisting status as an art center of sorts. To understand this schism it is worth making the following general remark: the great majority of writings uploaded onto online journals and magazines dedicated to art in Philadelphia are focused on the distinctively contemporary character of the city’s art. Very little is written about other art. I have not read much writing on the preexisting art institutions or art collections such as, for example, the Rodin Museum or the Duchamp collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This is interesting considering that both the Rodin Museum and the Duchamp collection are institutionalized forms that facilitate the immediate recognition of the international status of Philadelphia as a cultural hub.

The Rodin-Duchamp example is worth pursuing further since it points to what kind of internationalism Philadelphia actually embodies. The artwork most powerfully associated with Philadelphia is European avant-garde and modern art, which renders Philadelphia’s internationalism anachronistic vis-à-vis contemporary art. Or, more precisely put, Philadelphia’s contemporaneity–since the contemporary is the most dominant form of recognizing the globalization of internationalism–is sustained almost exclusively by the institutionalized interest in the art of the European past. (One wonders what the recent acquisition of the Sachs collection by the PMA will do to this anachronism, a collection that not only showcases post-war American artists, but also incorporates artists from the rest of the world.)

In order to raise Philadelphia to the level of global recognition, perhaps it is necessary to tackle the issue of the institutional domination of the internationalization of art as the medium through which the city is constantly made “culturally relevant” on the global scene.

Questions for contemporary art in Philadelphia

Tackling the problem of this institutionalized mediation, however, should not result in the production of a distinctively parochial identification of a ‘Philadelphian art,’ since this almost automatically leads to either an ignorance of the complexity of the mediating function of the globalization of contemporary art or a naïve dissociation from the preexisting ideological image of what kind of art city Philadelphia is.

I believe that this parochialism is a central problem of recent discourse on contemporary art in Philadelphia in the DIY scene.

To close, I would like to offer the following two questions by way of an attempt to stimulate further reflections and counter-reflections. First, is it possible to have a ‘contemporary art discourse’ in Philadelphia if, on the one hand, the central focus is the geo-political and cultural specificity of the city itself and, on the other, contemporary art is by definition globalized? Second, should we focus on Philadelphia if we are trying to internationalize the debate?