“I ask no monument, proud and high to arrest the gaze of passers-by; all that my yearning spirit craves, is bury me not in a land of slaves.”

–Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, 1858

2016 AD

One hundred and fifty-eight years ago, abolitionist, suffragist, poet, and author Frances Ellen Watkins Harper wrote these words, which are engraved on the wall of the Contemplative Court in the new National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), the Smithsonian’s latest and last contribution to the National Mall. I wonder what she would write today in a country in which the number of incarcerated black males is exponentially greater than the number of enslaved Africans who were forcibly brought to our shores.

The horrors of the institution of slavery, which lasted for hundreds of years, are unimaginable. It was by far the largest forced migration of people in the history of the world. The history of that institution as it relates to our country, continuing through the eras of reconstruction, segregation, and the civil rights movement, and highlighting the impact of African Americans on life in America from the death of Martin Luther King to the second election of Barack Obama–including the Black Arts Movement, Hip Hop, the Black Panthers, “Yes We Can,” Black is Beautiful, #BlackLivesMatter–is boldly recounted in NMAAHC’s three underground floors of multi-media displays, artifacts, objects, and text which you need a full day and nerves of steel to absorb. The effect is nothing short of devastating. I spent the day of my visit unable to get out of my head the image of a 12-year old African child in 1787 being ripped away from his mother, kidnapped, then shackled to a post in the bowels of a ship (the ‘Middle Passage’) bound for a sugar plantation on another continent where his life expectancy would be seven years if he survived the journey.

The Community and Culture Galleries

NMAAHC’s stunning Community and Culture Galleries highlight, in rich, historic multi-media displays, the contributions that African Americans have made in the arts, music, theater, entertainment and fashion, as well as in the military, sports, politics and the civil rights movement. I cannot even begin to describe these wonderful documentary exhibits which brilliantly spotlight the evolving sensibilities, talents, and accomplishments of African Americans and their enormous, invaluable contributions to the culture of our country. Louis Armstrong, Sonia Sanchez, Carl Lewis, Paul Robeson, Ntozake Shange, Ann Lowe, Langston Hughes, Shirley Chisholm, Maya Angelou, Rosa Parks, and Marian Anderson, among many others, are featured in these galleries.

Visual art and the American experience

NMAAHC’s visual art gallery occupies a small section of the fourth floor of the museum, among its Culture Galleries. It is separated into eight subsections, each containing a handful of art works–New Materials, New Worlds; The Beauty of Color and Form; African Connections; The Politics of Identity; Religion and Spirituality; The Struggle for Freedom; The World Around Us; Myth, Memory and Reality. Many of the works displayed are from the NMAAHC’s own collection, with a sprinkling of pieces on loan from other institutions and individuals.

The laudable intent of the curators, Jacquelyn D. Serwer and Tuliza Fleming, is to present examples of the work of African American artists beginning in the early years of the 19th century, such as the self-taught Joshua Johnson, who was born a slave, and continuing to the present, with contemporary artists such as Jefferson Pinder and Chakaia Booker, in order to demonstrate how these artists viewed and commented upon their world. The curators also make a conscious effort to select works which incorporate African culture–“symbols of pride that link them to their cultural heritage.”

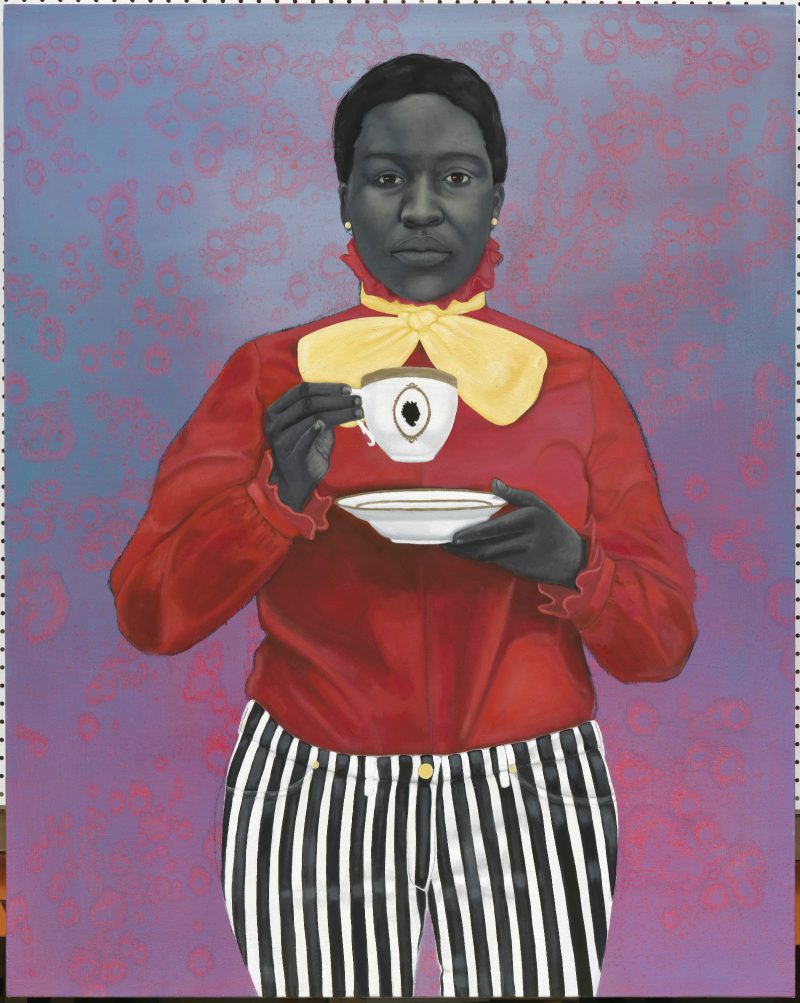

The collection contains the work of both well-known and unknown African American artists, among them: Renée Stout, Romare Bearden, Charles Alston, Thelma Johnson Streat, Grafton Tyler Brown, Amy Sherald, Bob Thompson, Adger Cowens, Floyd Coleman, Beauford Delany, Kara Walker, Betye Saar, Edward Clark, and Wadsworth Aikens Jarrell. Prominently displayed is Whitfield Lovell’s “The Card Series II: The Rounds” (2006-2011), 54 portraits of anonymous African Americans who lived between the 1863 “Emancipation Proclamation” and the civil rights movement, which were derived from a 19th-century deck of “Sutherland’s Circular Coon Cards,” a series of offensive caricatures of African American men.

There are a number of pieces in the collection which I found exceptional; however, NMAAHC was not able to provide permission for Artblog to publish images of them: Jacob Lawrence (“Dixie Café,” 1948); Elizabeth Catlett (“Negro Es Bello 1 – Black is Beautiful,” 1968); William H. Johnson (“Off to War,” 1942-44); Archibald Motley, Jr. (“The Argument,” 1940); McArthur Binion (“Rutabaga: No: The Sky,” 1978-79); and a striking sculpture by the Nigerian artist, Olowe of Ise (“Veranda Post,” pre-1938), which helped inspire David Adjaye’s design of the museum, about which much has already been written (Dodie Kazanjian, “With His New Historic Design, Architect David Adjaye Has Hit The Top,” Vogue, June 21, 2016); Inga Saffron, “Changing Skyline: With new D.C. museum, the African American story moves to nation’s main stage,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 15, 2016). Although I have not been able to find an image of this particular sculpture on the internet, it is quite similar to others created by the artist.

To recognize and to do justice to the centuries-long history of art by African Americans would require a museum dedicated exclusively to that. The NMAAHC attempts in a relatively small space to capture representative exemplars from that history. Unfortunately, I don’t believe that the museum accomplishes its goal; indeed, I doubt whether a dedicated African American art museum could accomplish that. Hopefully the collection will evolve over time, but at this early point in the life of the museum, there are just too many voices missing from the collection, particularly the voices of contemporary African American artists, as well as the work of outsiders and the avant-garde. To name just a few of the missing: Hank Willis Thomas, Juliana Huxtable, Jean-Michel Basquait, Kerry James Marshall, Hank Willis Thomas, Bill Traylor, Joseph Yoakum, Maren Hassinger, Ulysses Jenkins, Barbara McCullough, and Senga Nengudi.

Vinson Cunningham, writing in The New Yorker, has suggested that the NMAAHC’s fine arts collection more effectively interprets African American history than its artifact-rich, fact-based history galleries. In Cunningham’s opinion, the history galleries focus too heavily upon the literal progress of black advancement and do not sufficiently comment upon “which means, and which strategies, have secured this progress, or how it might be sustained and enlarged.” (Vinson Cunningham, “Making a Home for Black History,” The New Yorker, August 29, 2016). He also takes the museum to task for failing to promote a dialogue in connection with its presentation of history that might invite controversy and dissent.

Without underestimating the importance of the commentary that Cunningham finds missing from NMAAHC’s history galleries, there is no question that the museum provides a thorough fact-based presentation of the history that must be a predicate to any such critical or controversial commentary.

This gets me to the issue of audience. Certainly this museum’s vision–as with all Smithsonian museums–is to reach a broad audience that includes all races, ages, and ethnicities. Sadly, many in this broad audience, for reasons having to do with the “whitewashing” of history in this country, will be shocked by the documentary evidence of historical evil. Indeed, I suspect that many, if not most of us, come to the museum with an inadequate knowledge and understanding of that history, and I wonder whether Cunningham is failing to take that into account.

Finally, although I agree that art can further the dialogue–that art almost by definition is interpretive to a degree that the bare presentation of history cannot be–as I have discussed here, my impression is that the museum’s collection at this point is not sufficiently extensive or wide-ranging enough “to communicate the power of events” or “to achieve a kind of lift, away from the time line and into deeper places” that Cunningham finds lacking in the history galleries.

I do think though that NMAAHC captures the striking variety of work produced by African American artists over time, and this is consistent with one of the museum’s overarching goals: to “[raise] the profile of American artists of African descent from the periphery of the American art canon to its center and [replace] the moniker, ‘African American art,’ with the more appropriate designation of American art.” Antwaun Sargent has written an illuminating review of the collection, in which he suggests that there is a tension between this curatorial objective, which the museum has in part realized by presenting work “in ways that contest or question the notion of a monolithic black identity,” and much of the artwork itself, which demonstrates “the differences that have long separated the motivations of black artists from others in the canon . . .” Sargent concludes that, particularly in light of events such as the recent killings of unarmed black Americans, “which have led many in the black community to wonder how much has really changed,” the museum’s “presentation of art, like its detailing of history, should privilege the black voice.” Antwaun Sargent, “The Art in the Smithsonian’s New African-American Museum Gives a Powerful, Nuanced Portrait of Black Experience,” Art Sy (September 22, 2016).

It seems to me that NMAAHC has the opportunity, not yet fully realized, to bring to African American artists the attention and recognition they deserve, and to place them squarely in the cosmos of American art, and at the same time to “privilege the black voice.” Indeed, the museum brilliantly has accomplished that in its other Culture Galleries.

NMAAHC is located at 1400 Constitution Ave NW, Washington, DC 20560, adjacent to the Washington Monument. To read extensive overviews of the museum, see Stephan Salisbury’s September 21, 2016 article in the Philadelphia Inquirer: “New museum on National Mall tells sweeping story of black experience – with a Philly twist”; Benjamin Freed’s May 13, 2016 article in the Washingtonian: “Look Inside the National Museum of African American History and Culture”; and The New York Times, September 15, 2016: “I, Too, Sing America.”

I visited NMAAHC a week after it opened to the public, and it was packed. Indeed, online ticket sales are now sold out through March. Although on the day I visited it seemed as if most visitors were people of color, to my mind, every American, particularly every Caucasian, should visit, if only to better appreciate, recognize, acknowledge, and in some personal way to address the long, shameful history of slavery and the oppression African Americans have faced in our country.