“It’s hard enough to start a revolution, even harder to sustain it, and hardest of all to win it. But it’s only afterwards, once we’ve won, that the real difficulties begin.”

– Ben M’hidi, FLN founding member portrayed in the film

Since the release of Gillo Pontecorvo’s “The Battle of Algiers” in 1966, the film remains one of the most revolutionary agitprops from the 20th century to have ever graced the silver screen. The fictional film, based on factual accounts of the seminal battle of the Algerian War against the French (1954-62), won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and was subsequently banned for five years in France for political reasons, until it was released in French theaters in 1971. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the film’s release, which is being commemorated with the release of a newly restored print.

A legendary film

With its depictions of urban guerrilla warfare and actual characters that waged the war, “The Battle of Algiers” has influenced the likes of filmmakers John Cassavetes, Costa-Gavras, Oliver Stone, as well as revolutionaries throughout the world like Che Guevera, Fidel Castro, the Black Panthers, the Provisional Irish Republic Army, and the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front. Even the United States government, in 2003, sought to review the film in an effort to learn more about the military and urban guerrilla tactics used by both political parties as depicted.

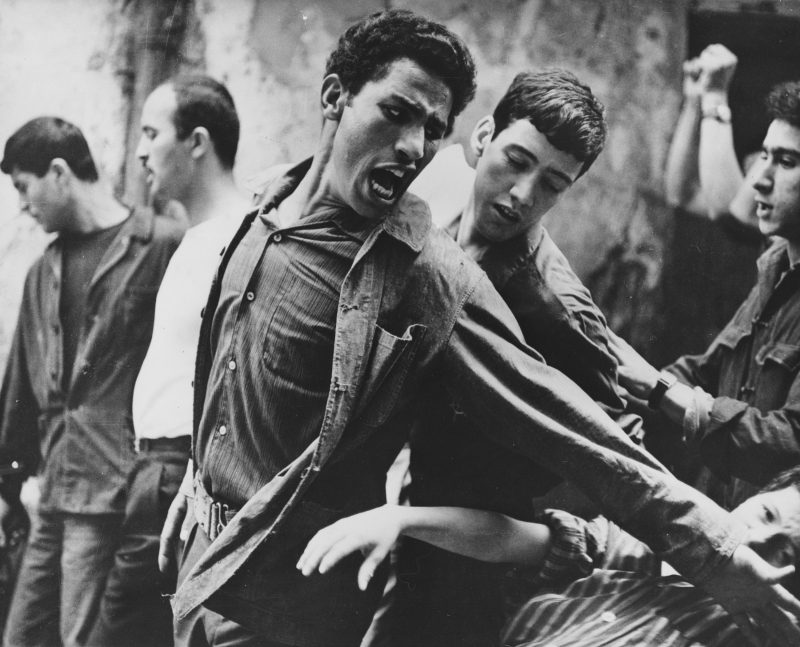

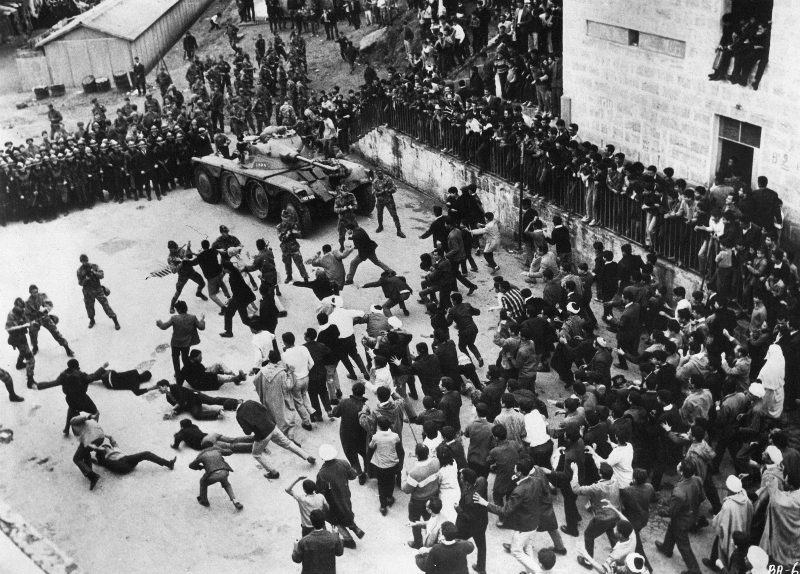

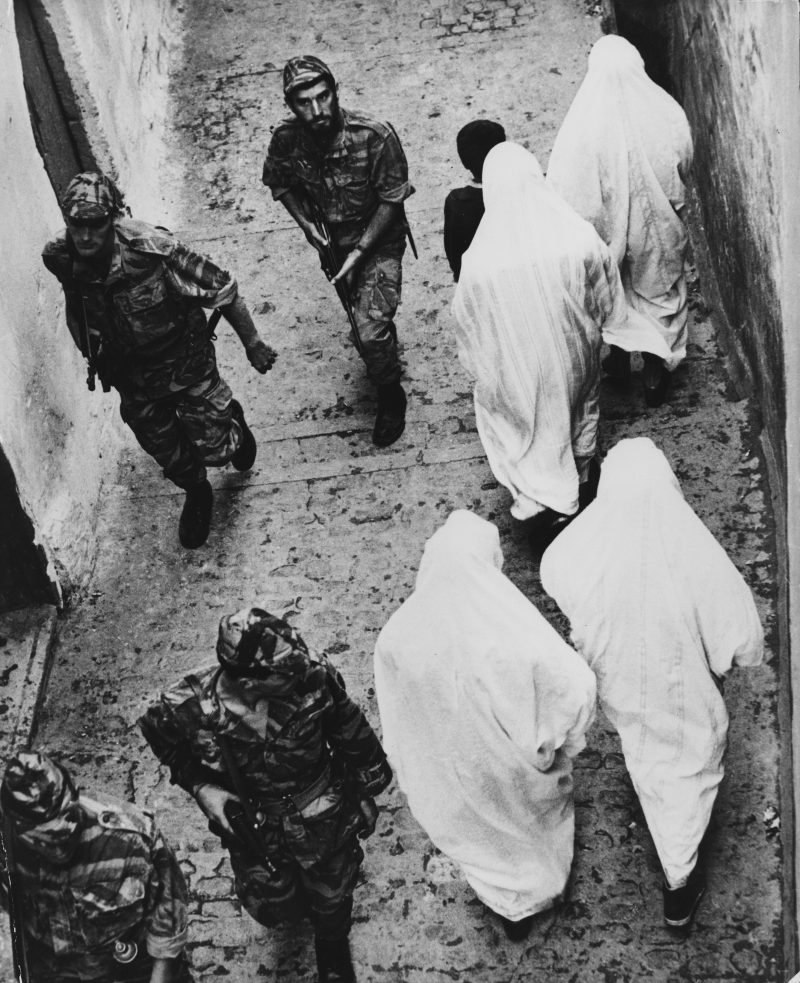

With dynamic camerawork and close-ups, along with stirring music that enhances the emotional impact of what’s shown, the moody black-and-white film focuses on the events during the French-Algerian War that claimed over a million lives, including those who were either caught up between the two warring factions, or who died in exile. Title cards punctuate these events as related by Pontecorvo in an effort to sum up the collective emergence of the Algerian people after being colonized for 130 years by the French. Mario Serandrei’s quick editing and Marcello Gatti’s riveting close-ups and continuously roving camerawork within the Casbah give the film its dynamic movement and action.

The collaboration between Pontecorvo and legendary music composer Ennio Morricone (“Once Upon a Time in the West,” “Cinema Paradiso,” “The Thing,” “Malena”) produces a haunting arrangement of military drums, horns, and pianos that amplifies the film’s revolutionary struggle for independence.

The addition of native sounds like the ululating of the Algerian women and the use of Gnawa music further heightens the tension of key scenes, such as the three FLN female members transforming themselves into Europeans in order to smuggle and plant the bombs in the European quarters.

Staging resistance

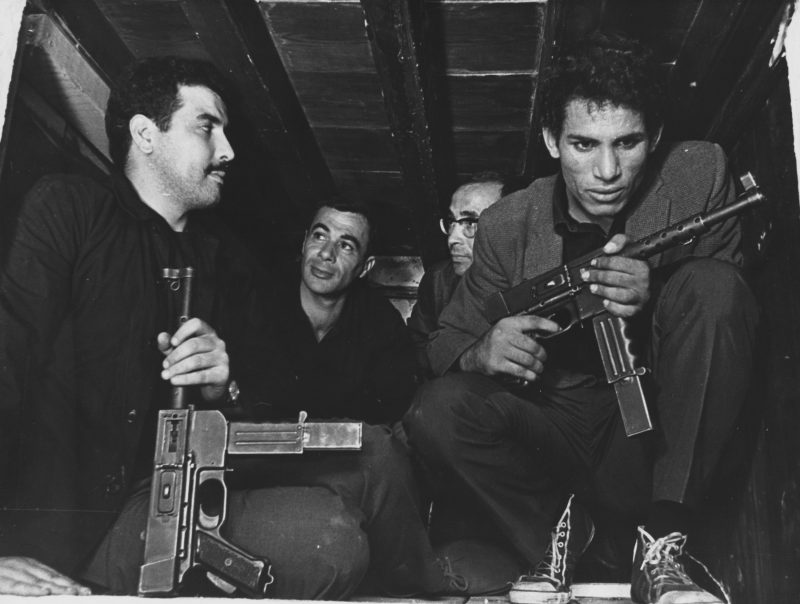

Two characters dominate the film–the Liberation National Front (FLN) member, Ali LaPointe, played by Brahim Haggiag, and Lieutenant-Colonel Mathieu, based on the French Paratrooper General Jacques Massu, played by Jean Martin. Both actors deliver credible performances as these diametrically opposed real life characters who are so focused on their objectives that they serve as poster boys for recruitment on their respective sides.

Other pivotal characters portrayed on screen are played by Algerian non-actors, some of who were FLN members in real life, notably Saadi Yacef, the leader of the FLN who plays a thinly fictionalized version of himself, who also wrote and produced the film.

Pontecorvo’s seamless integration of Algerian non-actors with French actors gives the film an authentic look, allowing for the non-actors’ familiarity with their culture, environments, and struggles in achieving their independence to be showcased on screen. Scenes in which Ben H’midi and Colonel Matthieu are interviewed by the press are particularly engaging as are the massive clashes between hundreds and thousands of protesters and the French Military that are meticulously staged.

Selective history

The film’s anti-colonial theme stems from its director’s own brush with forced authority. As a middle-class Jew living in fascist Italy, anti-Semitic laws restricted Pontecorvo’s educational and professional opportunities. This forced a protracted move to Paris, where he had the good fortune to work with journalists and documentary filmmakers and be in the company of such influential figures like Picasso, Igor Stravinsky, and Jean-Paul Sartre.

These crucial events would lay the seeds of clandestine resistance to fascism that he later channeled as the head of the Italian communist youth organization. This life experience informs his work on the film.

Despite Pontecorvo’s presumed bias against anti-colonial struggles, I found that deciding on the protagonist and antagonist in the film depends on where your political views may lie–for this reason it could be regarded as a balanced film.

“The Battle of Algiers” is multi-dimensional. It is a work of art, but might be taken as leftist propaganda. In both cases, it is an oversimplification of a major political struggle in human history.

While even a documentary film will most likely fail to deliver all of the story–and this is not a documentary though it is shot in a newsreel style–“The Battle of Algiers” overlooks some history that would have made its story more nuanced and perhaps less stirring.

Delving into the film’s references to events and characters, I found the film to be highly selective and have overlooked certain players and groups in the real revolution who were edited out to present the FLN in a sympathetic light.

The FLN was tainted by jealousies, and some of its less than purely idealistic actions are not in the movie. For example, Abane Ramdane, a long-time nationalist and political force who was considered the “architect of the revolution” is nowhere in the film. He was later killed by the FLN because they feared the cult of personality growing up around him.

Another example that alludes to a scrubbing of FLN history is the Algerian National Movement, founded as a rival to the FLN (some say with French backing) but which disappeared after FLN fought them (literally) for dominance in what came to be known as the Café Wars, and won.

In thinking of the colonial oppression of the Algerian people, it is important to remind ourselves that the French were occupied and oppressed by Nazi Germany only a few years before this film’s setting. The French Vichy regime and an organized French underground were divided ideologically during the German occupation. While it is difficult to sympathize with the French government and military in this movie, it is necessary to think of the broader geo-political world outside of the Casbah.

Whether it was intended or not, “The Battle of Algiers” provides a visual blueprint for urban warfare. Its sympathetic portrayal of the guerrillas celebrates the freedom fighters but does not show a path beyond urban warfare and into peaceful resolution. I can only hope that new viewers of the film will understand the lessons it has to offer and not just absorb the blueprint.

To my mind, the key lessons in the film, ironically, are against guerrilla warfare. The film shows the price paid for freedom–huge loss of life and an unclear future. Underneath the celebration of the guerrillas, “The Battle” tells us that a guerrilla insurgency, no matter how noble, with all the carnage that ensues, is too high a price to pay for freedom. In looking at examples from the wars currently being fought in the Middle East, the oppressor and the resistance fighter wage the same kind of battles we see in the film. Back in our homes we see almost daily news scenes in which bombs explode in cafes and bars, or civilians are gunned down indiscriminately during massive protests.

Violence and oppression are still dancing together.

The new 50th Anniversary 4K restoration of “The Battle of Algiers” opens at the Ritz At the Bourse on Oct. 14.