“In our minds there is an awareness of perfection and when we look with our eyes we see it.”

– Agnes Martin

A retrospective

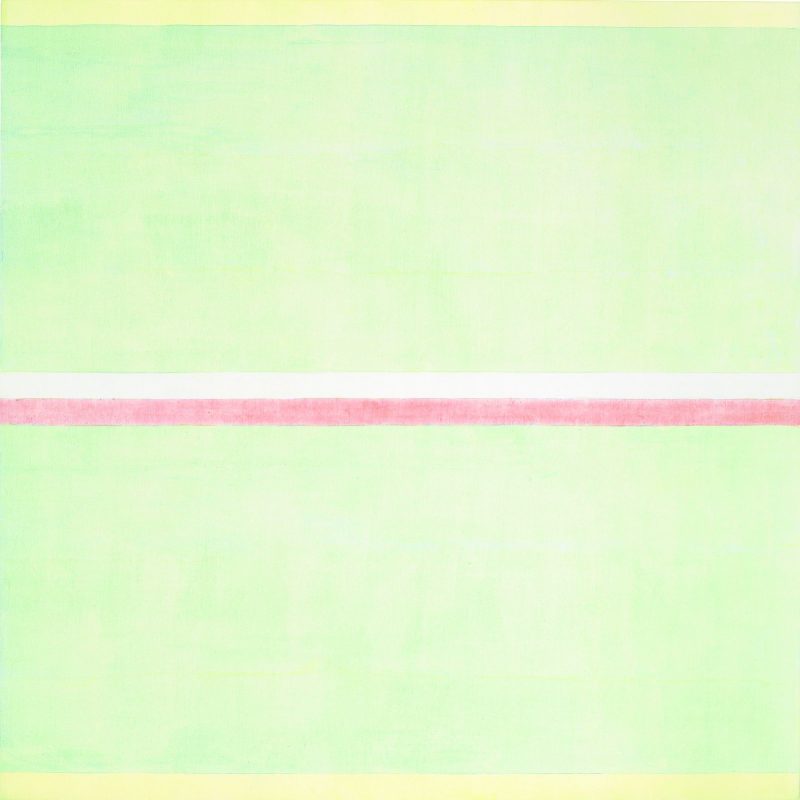

Agnes Martin overcame the effects of mental illness, which she suffered from for most of her adult life, to produce a body of work that distinguished her as one of the preeminent painters of the twentieth century. She was best known for her evocative paintings composed of grids and stripes, which were often inscribed with pencil lines, such as the stunning “Gratitude,” pictured above. The Guggenheim’s retrospective–the first in more than 20 years–includes 115 of Martin’s paintings and drawings and traces the entirety of her career from the 1950s through the early 2000s.

If you begin at the top of the museum’s rotunda, as I did, you spiral down through Martin’s life and trace her development as an artist reeling backward in time, and it is a fantastic journey very similar to what you may experience if you immerse yourself within her mesmerizing and zen-like paintings. With its open bays in which the art is situated, the light and the vistas of the Guggenheim provide an an ideal showcase for Martin’s work, much of which was inspired by the singular and magnificent spectrum of light and limitless space of New Mexico, where she lived for a good portion of her life.

Above the line – the striped paintings

For the most part, Martin’s paintings are purely abstract. In the catalogue accompanying the first retrospective of her work in 1973 at Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art, she emphasized that her paintings “have neither objects, nor space, not time, not anything, no forms.” She sought in her work to evoke the feelings associated with the perception of beauty in nature and the freedom one feels in the natural world.

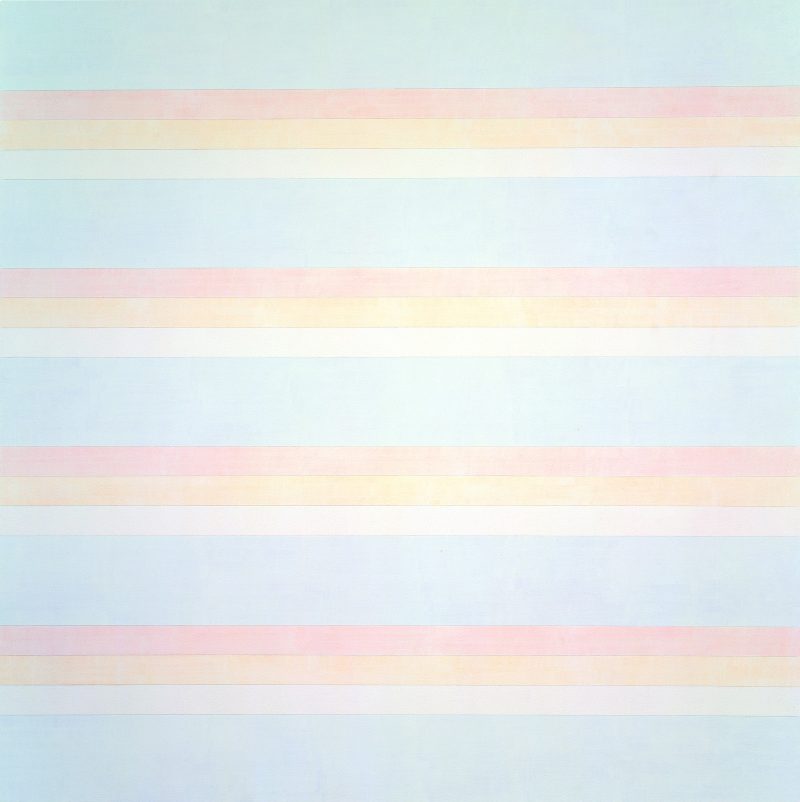

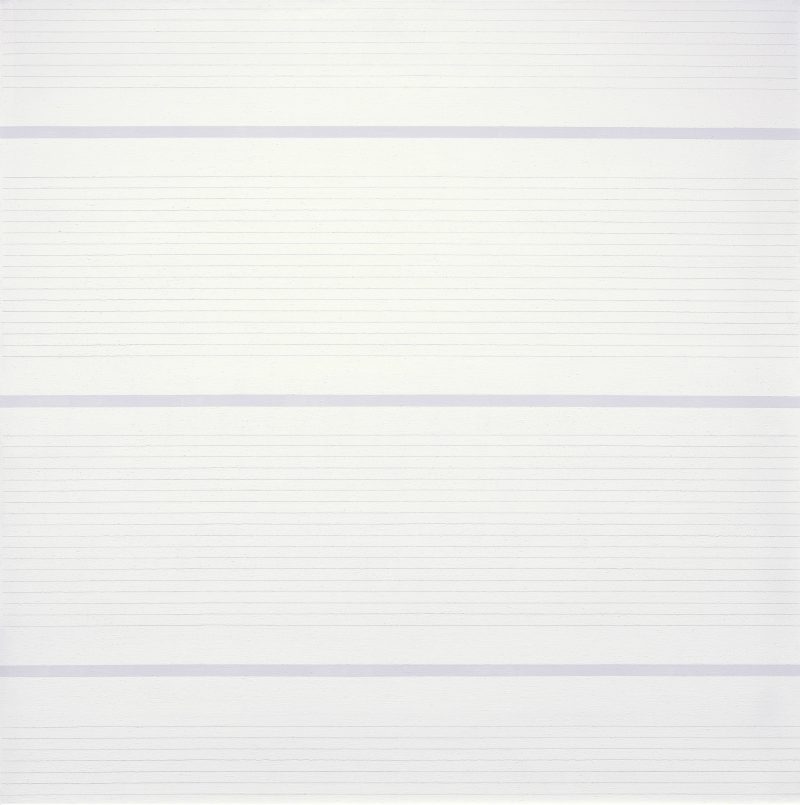

Martin’s striped paintings, such as “Gratitude” and “Untitled #2,” pictured here–soft acrylic washes thinly applied over layers of gesso in pinks, blues, and yellows–are beautiful, tranquil, serene, meditative, pristine, innocent, and exquisitely spare. They fulfill the artist’s intention to evoke abstract positive emotions, emotions “above the line”–happiness, love, and experiences of innocence, freedom, beauty, and perfection. “I would like [my pictures] to represent beauty, innocence and happiness,” Martin said. “I would like them all to represent that. Exaltation.”

Martin painted when she was inspired, and she painted with what she described as an empty mind, seeking an emotional truth with humility and apart from ideas and from ego. She once commented that the best things in life happen when you are alone.

Below the line – the grids

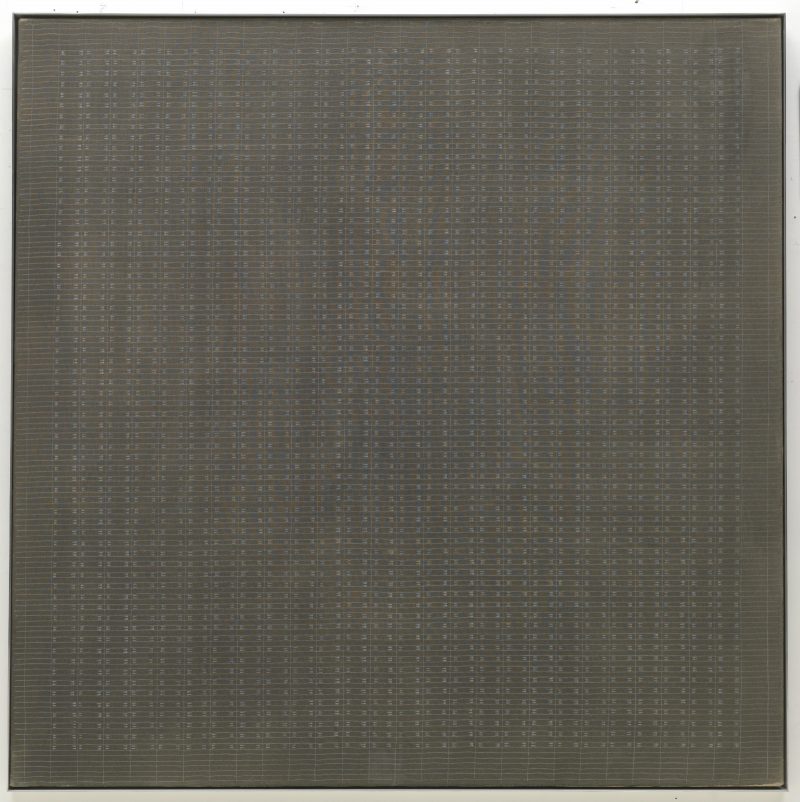

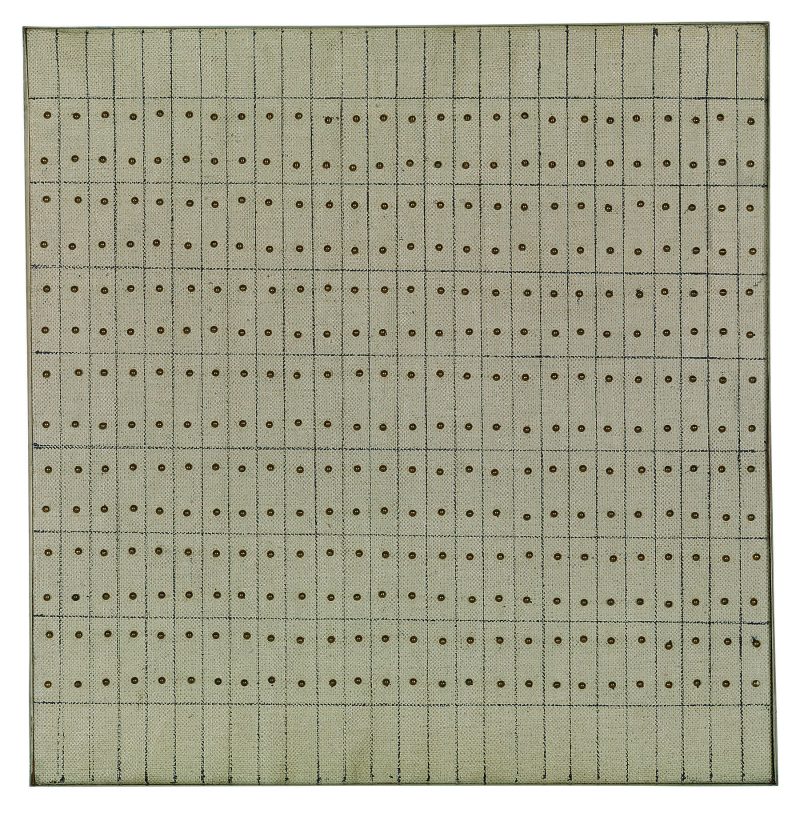

Martin did not distinguish her grid work from her striped paintings. “When I first made a grid I happened to be thinking of the innocence of trees, and I thought the grid represented innocence, and I still do,” Martin told Vogue in 1992. “Drawing the Line,” Vogue (November 1992). But there is a subterranean level of intensity added to her grids that I think is absent from the striped paintings, something she never acknowledged.

The artist liked to say that the viewer should spend a minute face to face with her paintings–that “a minute is quite a long time.” And spending a minute examining one of her grid paintings or drawings, moving, and perhaps lost, within its field, is utterly engrossing and powerful. At first glance, the constructions seem symmetrical, mechanical, reductive. But upon closer inspection, the eye travels on long horizontal lines or rows of small, sometimes dotted, rectangles, which waiver and fade, and then recover, all hand-drawn with the guidance of a small ruler. (Martin didn’t like squares, by the way, found them over-confident and aggressive.)

Each grid becomes a universe of simple, austere, restrained repetitions with subtle variations of line and tone which sweep you away. They are indelibly intimate, deeply intricate and expressionistic, and oftentimes lyrical. There is an element of strength, even courageousness to them. The grids remind me of the repetitive but quite lyrical music of Steve Reich. Martin, who thought of music as the highest art, likely would have been pleased with the comparison.

But there also is something disturbing in Martin’s extreme obsessiveness. There is tension and aggression woven into some of her grids. It is as if she was able to bind emotional chaos into them, but in a magically soothing fashion. One writer described her grids as “two-dimensional prisons”–positing that Martin’s use of line represented her “attempt to hold onto control.” There may be something to that statement, but I believe it overlooks the overarching beauty of the compositions. I think Alastair Sooke got it right when he referred to Martin as “the mistress of serenity and contemplation,” but suggested that “the tranquility of her art represents the calm following a storm.” “Agnes Martin, Tate Modern, review: ‘immaculate’”, The Telegraph (June 1, 2015).

At the end of the day, although we relish what Martin has painted above the line in her grids, at the same time we feel the dark pulse that simmers below.

Biography

A Canadian/American, Agnes Martin was born in 1912 and died in 2004. As an adult, she lived alternately in lower Manhattan and in New Mexico. Although she always lived alone, she apparently believed in reincarnation, and she suggested that in the past she may have lived lives of another nature.

During her years in New York, Martin hung around with a bunch of well-known minimalists and abstract expressionists including Elsworth Kelly, Jack Youngerman, Ad Reinhardt, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Indiana, James Rosenquist, and Barnett Newman. Although she considered herself more of an abstract expressionist than a minimalist, I think there is no question that her work bridged the two. She clearly was influenced by Reinhardt, Judd, Kelly, LeWitt, Newman, and of course by Mark Rothko. She also was influenced by her friend, the well-known fiber artist Lenore Tawney.

Martin was reclusive, but she was not unsophisticated. She was attracted to the music of John Cage, and she was interested in Taoism and Zen Buddhism. She could be unpredictable. At one point in her 50s, inexplicably, she quit painting altogether for a period of more than five years. During the early stages of her career, she often was dissatisfied with her work, and destroyed a great deal of it. Martin was austere, complicated, iconoclastic, enigmatic, and, anecdotally, I understand that she was not always easy to deal with. At least in the last phases of her life, she was a strange bird.

Further Sources

If you are interested in Martin’s biography, there’s a new one by the art critic/writer Nancy Princenthal, Agnes Martin: Her Life and Art.

Hilton Als has written a thoughtful and comprehensive review of Princenthal’s book, which he turned into a wonderful essay about Martin–“The Heroic Art of Agnes Martin”–in The New York Review of Books (July 14, 2016).

Jane Yong Kim’s piece about the book in the Los Angeles Review of Books–“A Deep but Unstable Joy: Gazing at Agnes Martin” (November 5, 2015), also is great.

Finally, there’s an illuminating documentary about Martin in her later years, produced and directed by the filmmaker Mary Lance, aptly entitled With My Back to the World (2002). For an interview with Lance about the film, see “Q&A With Mary Lance; ‘Reflections’ by Agnes Martin,” Bloom (January 14, 2015).

The Guggenheim retrospective has been organized by Tate Martin, London, in collaboration with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Curators for the exhibition, which will remain on display through January 11, 2017, are Tracey Bashkoff, Guggenheim’s Senior Curator, Collections and Exhibitions, and Tiffany Bell, Guest Curator.