Matthijs Ilsink and Jos Koldeweij, Hieronymus Bosch; Visions of genius (Brussels: Mercatorfonds and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016).

This wonderfully approachable monograph will delight readers who know and love Bosch’s paintings, as well as those unfamiliar with them or with his equally remarkable drawings. Its splendid illustrations include numerous enlarged details that enable an understanding that even seeing the paintings in person cannot offer–and Bosch’s work is very rich in small-scale events. Published as the catalog to the sold-out exhibition marking the 500th anniversary of the artist’s death by his hometown museum, Het Noordbrabants Museum, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, it is excellently written for the intelligent, generalist reader. It includes a summary introduction to the world in which Bosch functioned and to the artist himself, although the extant information about Bosch is limited–and none of it really accounts for his singular accomplishments. Bosch’s father and grandfather were painters working in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, and there is no evidence that Hieronymus traveled beyond his hometown, an artistic backwater. Yet he was the first artist from the Lowlands to sign his work, which was known and collected by princes and nobility across Europe.

The text does a great deal to make sense of the rich stories told through details that a viewer might overlook, and as such it is a lesson in close observation. In the text for “The Wayfarer,” a subject with no painted precedent, the authors point out that there are all sorts of dubious goings-on at the tavern he has just passed–the inverted jug that sticks up from the apex of the gable, the underwear hanging from the window, the little swan on the inn sign, the man urinating around the corner, … None of these details were included by accident, nor were they simply recording the world seen by the artist, and the authors bring in a rich variety of sources, from folk stories to traditional Christian representations.

Bosch is the first Flemish artist for whom a body of drawings survive, and if readers have never seen one of his drawings, this part of the catalog is likely to be a revelation. Bosch loved owls, and they appear in numerous paintings and drawings, including one rarity, a drawing likely done from observation. Most of the drawings are sheets with multiple sketches of individuals or small groups of figures–from peasants to monsters–that could be used by the artist and his workshop for inclusion within paintings. Readers interested in more scholarly information on the artist that resulted from the six years of research preceding the exhibition can consult an excellent website, or two further publications, one a catalog raisonné, the other a collection of technical studies, both distributed by Yale University Press.

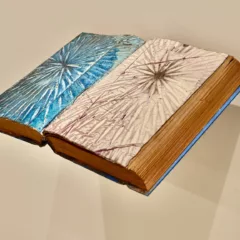

Painting 2.0: Expression in the Information Age, edited by Manuela Ammer, Achim Hochdörfer, and David Joselit (Munich: Prestel, 2015).

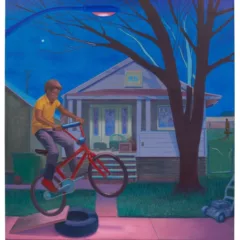

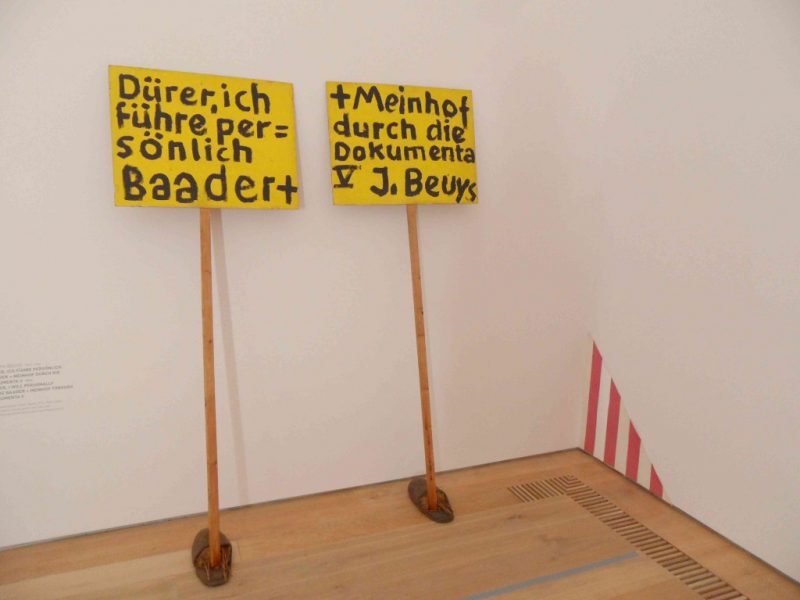

Reports of the death of painting, like that of Mark Twain, have been exaggerated. This catalog to an exhibition organized by museums in Munich and Vienna posits a history of painting during the past fifty years that is alternative to the formalist orthodoxy. Substantial essays by each of the three curator/editors explain their selection of artworks and ground their story in artists’ responses to mass media and the digital age. They cover the incorporation of readymades, advertising, film, video, and performance into painting, as well as the recuperation and re-formatting of modern forms and the re-assembling of existing art histories. The inclusion of “Expressionism” in the title is the most obvious indication of their radical propositions. Rather than associating the term with personal emotion writ large, they suggest an expressionism of gestural marks used to undermine spectacle and as political protest; embodied gestures that engage the subjective as well as material experiences of being a body; and gestures that move beyond the canvas and into the world.

The catalog will interest many readers concerned with contemporary painting, whether or not they wish to follow the curators’ fairly dense essays and/or agree with their arguments. The excellent illustrations provide a visual story line that challenges received ideas. It is a Euro-American story, with predominantly German and U.S. artists, and it is not clear how much it was determined by the collections of the two organizing museums and a number of European collections to which they had access. The flexibility of their definition of painting is indicated by the inclusion of performances by Günter Brus (“Self-Painting,” 1964/2005), Adrian Piper (“Catalysis III,” 1970/ c.1998), and Andrea Fraser (video of “May I help You?” 1991), objects by Paul Thek (a chair with leather belts, twine and paint, “Untitled,” 1968), Isa Genzken (a mannequin with painted clothing, “Untitled,” 2012), and Rosemarie Trockel (a knitted balaclava in a cardboard box, “Balaklava Nr. 4, 1986), installations by Ree Morton (“Signs of Love,” 1976) and Guyton\Walker (paint and ink-jet on canvas, drywall lifts, ink-jet prints on paint cans and crate,… “Untitled,” 2009), video by Joan Jonas (“Left Side Right Side,” 1972) and film by Andy Warhol (“Screen Tests,” 1964-65). While those artists might not surprise anyone who follows international art periodicals, others go beyond the usual suspects–Martin Wong, Harmony Hammond, Ed Paschke, Mary Grigoriadis. Short essays by Wolfram Pichler, Tonio Kroener, Lynne Cooke, Isabelle Graw, Kerstin Stakemeier, and John Kelsey introduce still further ideas about painting’s recent history.

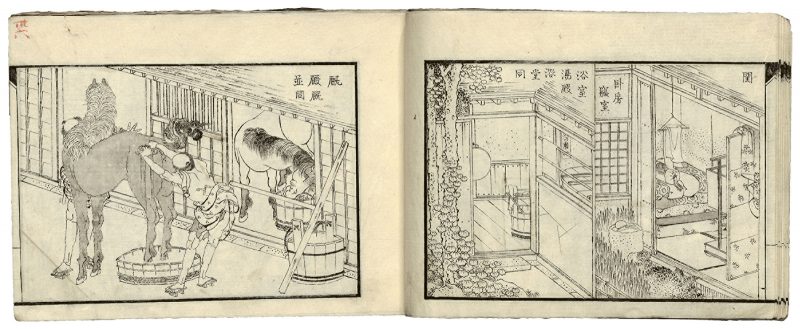

Sarah E. Thompson, Hokusai’s Lost Manga (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts Publications, 2016).

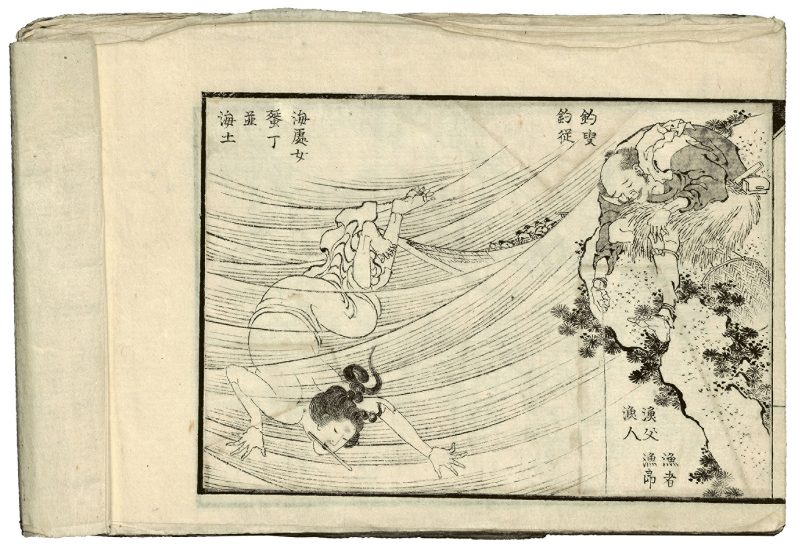

This publication is the result of one of those relatively rare but exciting discoveries in the depths of a large museum’s store rooms–an album of drawings by one of the great illustrators and print designers, Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849). Moreover, it likely corresponds to the original drawings for one of his announced, but never-printed, best-selling books of illustrations. It was billed as Master Iitsu’s Chicken-Rib Picture Book; Iitsu was one of Hokusai’s more than thirty aliases, and the term “chicken-rib” refers to a Chinese literary term for something trivial but worthwhile–like the bits of chicken left on the rib bones. The curator Sarah Thompson translates this as “tasty morsels,” and this publication of Hokusai’s images along with Thompson’s piquant prose is a tasty morsel indeed.

While the term manga has come to be associated with graphic narrative, in Hokusai’s period it simply meant “informal drawings.” Woodblock editions of manga on varied subjects were originally intended as pattern books for aspiring artists, but acquired a broader following which enjoyed their virtuosic draughtsmanship and their often humorous depictions of everyday life. Master Iitsu’s album includes subjects of urban popular culture–the pleasure district, theater, street markets, as well as religious imagery, dragons, landscapes, flowers, astronomy, and perhaps most interesting, depictions of a variety of trades including building construction, sericulture, and rope-making. Among my favorites are a double-page spread of a group of men hauling an enormous log, intended as a roof beam–Thompson points out that the man standing at center is holding a fan to mark the timing of their efforts, and another drawing of the Wind God, releasing his winds from a bundle wrapped around his shoulders. But it’s hard to choose, since I was also delighted by the group of men surrounding a huge tentacle of an octopus, draped over a rope; it is several times their height, which exaggerates the known size of any Pacific octopus.

In an introductory essay, Thompson situates the popular publishing industry within Japan’s social conditions, particularly the increasingly literate, urban middle class; she also discusses the place of Hokusai within a tradition of illustrators. The reason this album survives is unknown; had it been published, the drawings would have been destroyed by the block carvers as part of their process. Hokusai may have found a buyer willing to pay more for the intact album than he would have made on the printed edition, or the circumstances of the artist’s life may have interfered with his plans. Readers who follow Thompson’s annotations for the drawings will come out with a fascinating view of a range of Japanese life at the time, including such particularities as the fact that silkworm eggs were sold on pieces of paper that were packaged in envelopes, or the range of edible wild-flowers that they considered delicacies. These tasty morsels can be enjoyed at any time of day.