“Not a gallery”

Walking into Temple Contemporary at Tyler School of Art prompts the question: is this a gallery, a jam-packed store room, or what?

No empty wall space exists between the 11 artworks hung on the walls and ceiling, so an unaccustomed viewer needs to step back and consider the whole, or wait for a “conversation starter” to explain what’s going on.

The unusual combination of works appears to represent studies of the human condition–music stilled, broken bones, poverty, torture, a near-death experience, and more. The works are crammed together, much like the city, much like Temple University itself, as they present artists’ views of disparate problems facing us.

Yet, the works in Temple Contemporary are meant to convey so much more, according to Robert Blackson, director of Temple Contemporary and public programs, who insists the huge room of artworks–not for sale–is “not a gallery” despite its first floor location in Tyler School of Art on Temple’s campus on Norris Street at 12th.

Blackson wants the students and the public to reimagine the social function of art and the concept of a “gallery.” The works are intended to generate discussions of current issues worldwide, normally discussed in other university departments such as social welfare, psychology, the environment, music, and history.

Each year, Blackson and assistant director Sarah Biemiller ask the gallery’s 36 advisors–students, faculty and business and community leaders–to vote on conceptual questions for the space each year. This year’s four questions were: How and why do we fix things? How do we define public interest? What is an ally? What do reparations look like?

The artworks apparently meet that criterion.

Fixing things

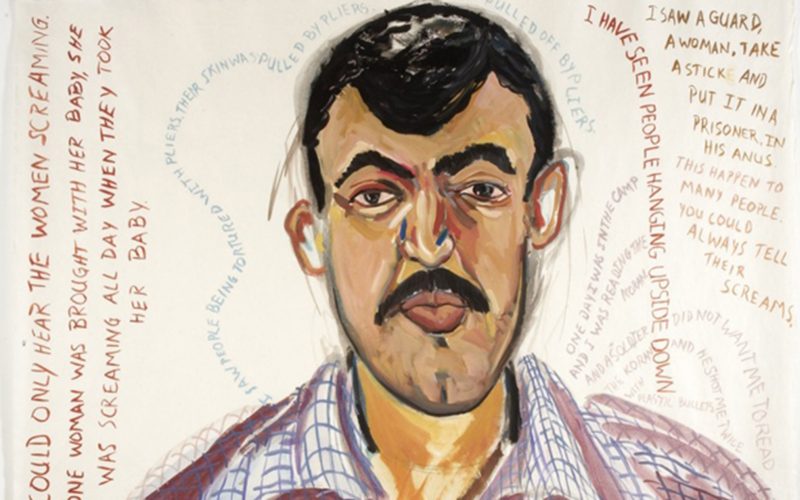

For example, 10 powerful brown ink drawings of innocent Iraqi prisoners, whose handwritten accounts of torture in Abu Ghraib and other prisons surround their portraits, were selected by artist Daniel Heyman. Heyman was asked to give a lecture after he and lawyer Susan L. Burke traveled to the Middle East to listen to prisoners’ testimony during U.S. investigative hearings between 2006-2008. Heyman’s work could fall under public interest, reparations and, possibly, ally.

Similarly, “Symphony for a Broken Orchestra” involves an impressive collection of 1,500 broken musical instruments lining three huge walls. The sound of each broken instrument will be recorded and, with these sounds, composer David Lang will create a “symphony” before the instruments are repaired with the help of $300,000 from the PEW and Barra foundations, and returned to the Philadelphia School District. The symphony is expected to be performed at the gallery.

Want and waste

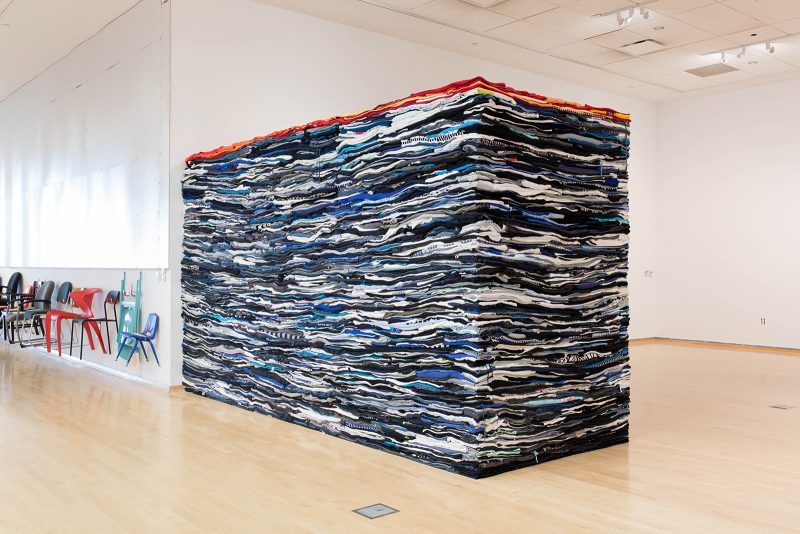

Artist Derek Melander has been working with used discarded clothing in unusual monumental shapes for several years, to bring attention to the immense textile waste generated daily. That is why he has neatly folded three tons–yes, you read that right–of worn, faded, stained and stretched second-hand clothes in an untitled work in the space. Melander wants viewers to think about those who wore clothes and threw them away, the space they now occupy and the larger issues of want and waste.

Yet, Melander’s immense rectangular shape–about eight feet high, maybe 20-feet long by five feet wide–is so imposing that it separates Temple’s L-shaped space in two, creating a synchronicity between Melander’s work and hundreds of open suitcases piled against a wall making one wonder if perhaps the cases were used to transport the discarded wearables.

But, no, this is a case of serendipity. The cases belong to the broken musical instruments in “Symphony for a Broken Orchestra,” and not connected to Melander’s work, according to Destiny Palmer, one of three graduate assistants called “conversation starters.”

Transmutations

Suspended from the ceiling is half of a VW Passat, titled “Transmutation of Tristin’s Passat” by artist Tristin Lowe, who had a near death experience after totaling the car on a dark rural road. Lowe wants the viewers to contemplate such life and death experiences.

“Reparations,“ a painting by artist Catherine Wagner, shows nine white splints for specific body parts on a black canvas. The artist says these bandages support healing physically, culturally, and spiritually.

“Please Have a Seat” is a collection of 76 different styles of chairs, loaned for a year by social service or city organizations to Temple Contemporary, as a way to recognize their ongoing contributions. Usually, each artist delivers a free lecture about his or her work to students and visitors, who sit on the donated chairs on exhibit. Afterwards, they return the chairs to their wall hooks.

Asked if he was taking gallery space away from Tyler students showing their artwork, Blackson says there are other galleries elsewhere in the building for them.

“There are tons of galleries in the city where [Tyler students] can show their work,” he added.

The aim is to have a conversation about the works between the viewer and the conversation starter to think more broadly about the issues raised by the artworks.

Such are the workings of a space, formerly called a gallery.

These installations will be on view at Temple Contemporary through February 10, 2017. Temple Contemporary is located at 2001 N. 13th Street, and is open Wednesday through Sunday, 11–6 pm.