The night is warm for November, somewhere in the sixties, and I’m in El Museo Picasso de Barcelona. The street it’s on is thin and feels more like an alleyway than automobile thoroughfare. I laugh at the thought of an American SUV, like a monster truck, powering its way over mini coopers to the museum’s entrance. It’ll be Veteran’s Day soon in the States, Remembrance Day in the commonwealth, but I’m in Spain, and by coincidence or by cause the exhibit here is about war–Cubism and War: The Crystal and the Flame (21 Oct–29 Jan 2017). Next to an array of both horrific an oddly endearing war photos, I see a letter encased in glass. The artist Henri Laurens writes to financier Leonce Rosenberg: “…We must be wary of good taste, beautiful colors, and compositions. The mind must be king, to the detriment of all that flatters the eye. If the road is rocky and unpaved, all the better if it leads to purity. It will never be rough enough to discourage the superficial.”

But this is also the plight of artists under duress: paint, draw, duck, hide, peek, draw again. The exhibit reveals the cubists in Paris were never far from the external specter of ruin, and evidently leery of the internal one. The war to end all wars was only a few hours away, and two of their own had been sent to fight. This is what artists wrestle with, have wrestled with, which is to say we’ve heard it all before: artists respond to their volatile world. Cubism and War is noteworthy in that it pushes to the forefront the turbulent backdrop of a crucial span of the cubists’ movement. And with a focus on the Spanish-speaking world, it includes gems like the evolution of famed Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. The exhibit is generous in its scope and delivers on showing a collision of worlds, a real one and an artistic one.

Specters of influence

Picasso is synonymous with, at least in pop culture, indecipherable modern art. He and Manet, though, were both concerned with breaking away from what art was supposed to be, to arrive at what it actually is. And by this they meant bringing it closer to Earth, to the way things are at the core. We know Picasso’s masterpiece “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” was influenced by African art, that he was influenced by Oceanic art. In the analytic period of cubism it’s more evident Picasso is tinkering with the illusionist tendencies of academia, his father’s work, Picasso’s own work. We see the breakdown of a viewing experience. Yes, what happened to Picasso was African and Oceanic art. But what also happened to Picasso was Cézanne, which is to say Pablo Picasso happened upon a few Cézannes. I see it in “Montaña de Málaga,” “Paris,” and “Barcelona Rooftops.” These are in the museum’s permanent collection. Picasso himself is unabashed about the influence of Cézanne, those first deep inquiries into the eye’s reconciliation of space.

In Cubism and War there’s still the echo of Cézanne’s brushwork in the pieces that still include illusionism, but pieces like “Arlequín y mujer con collar” point to a departure from those times, a movement towards color and shape and a medium’s conformity to the two dimensional surface. As one of largest pieces in the exhibit, “Arlequín y mujer con collar” is the embodiment of fragmented space, abstracted nature, in this case figuration. With its wonky Josef Albers-like grey square-in-a-square background, the color of white sparingly implemented, a liberal use of black and blue within the subject’s area on the canvas, and lastly the parts of canvas dotted with black, it looks to me like a nod to his earlier use of newspaper in collage, the way those marks, those words and letters had worked for him in the past.

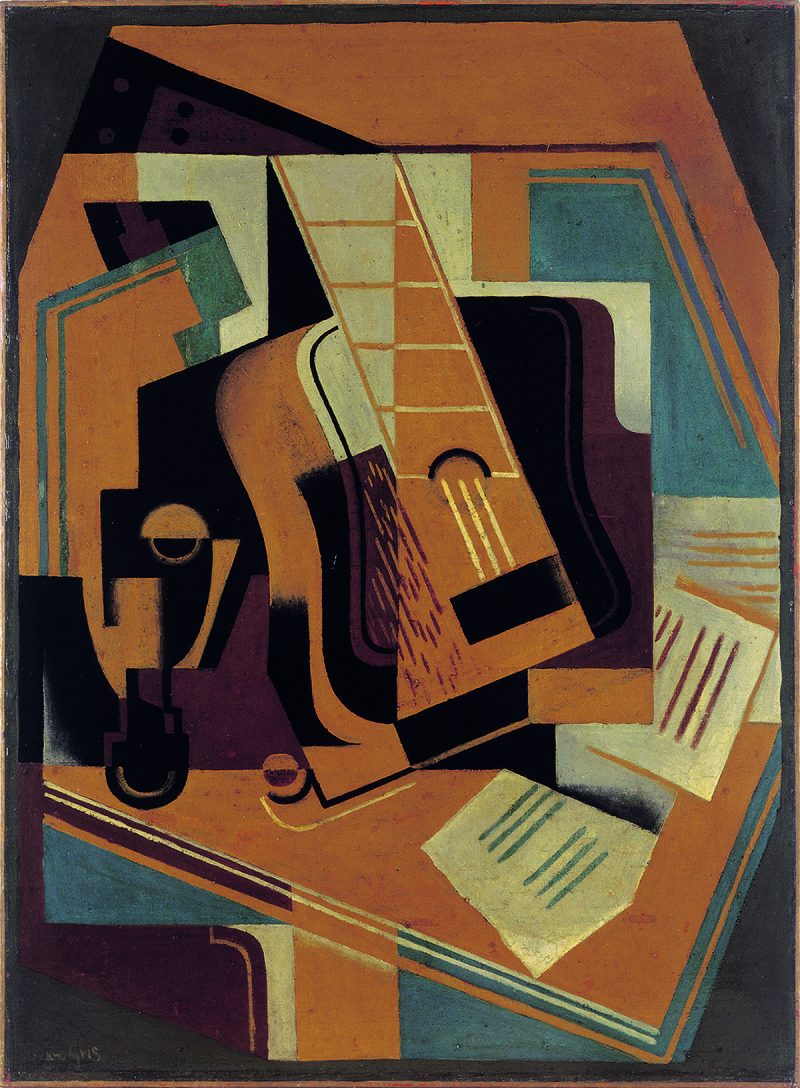

This is evident in Juan Gris’ piece “El paquete de café,” which is included in the show. Gris uses newspaper to reassign marks used for language, to repurpose them for their visual rather than semantic qualities, the need for language as a material and visual function of everything he sought to convey. Kitchen sink mode. In “El paquete de café,” we get content in earnest, the signified, a collection of signifiers as content and the optical finality of the arrangement, its resemblance to wood grain patterns, if we consider the space between words. Wood grains patterns are included in this piece, next to the news. Juan Gris leaves charcoal all over it, maybe as a wink to unification or the blurring of the exact nature of the separation.

Separation and rift

This is maybe what early cubism foreshadows, a separation. The war period saw a split between Picasso and his dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (he ended up with Paul Rosenberg instead). After 1914 he stopped making sculptures for fifteen years. Georges Braque, whose work inspired the critic Louis Vauxchelles to coin the term cubism, was sent to war. His postwar art is in the show, but the war left him badly injured, temporarily blind. The cubists were also split by the path of the movement itself. An essay by cubist-poet Pierre Reverdy criticized cubist portraiture and the artists responsible for it. Diego Rivera, who left Mexico for Madrid, and Madrid for Paris is said to have attacked Reverdy at an event in 1917, causing the community to part ways.

It makes sense then that Rivera’s work shows the most dramatic change over this period. Included in Cubism and War is Rivera’s foray into cubism. Having lived through the Mexican revolution, he was nudged overseas to study under artist Eduardo Chicharro. From there he headed to Montparnasse, Paris, where the major artists of the period gathered. Works like “Maternidad” and “Joven con suéter gris” demonstrate Rivera’s cubist chops, but also predict what would come next. In “Maternidad,” for example, the path of synthetic cubism is subverted to a degree, a critique of that sensibility by an endearing subject–a baby being breastfed by its fragmented mother. Her breast and the infant’s head share a nurturing purple. The deconstructed space is at odds with a subject matter that lends itself to a more naturalistic depiction, not an abstracted one. I’m torn before it. In a world at war, why is the future of art these high-end objects only the wealthy can buy? Rivera wrestled with this before ditching cubism and Paris to study frescoes in Italy.

Return to realism

But I believe it’s his piece “The Mathematician,” included in Cubism and War, that offers the most scathing rebuke. Rivera returns to his roots with a social realist portrait of a seated man. “The Mathematician” is a premonition, inhuman, a calculator as distant as the bartender in Manet’s “A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.” But unlike the lady in Manet’s piece, Rivera’s thinker is a bastion of solitude, at home in his own mind. Not lost on the artists of this period was the unprecedented use of applied science in weapons of war: the tank, the war plane, the new and improved machine gun. Death or untimely anti-life was being mass produced, better than ever. The mathematician’s upright, rigid posture aligns somewhat vertically with the canvas. The wall behind him is adorned with math diagrams, geometric shapes, lines, arrows, allusions to a kind of art-not-art. Rivera evades the end game path of his contemporaries like Picasso, whom artist Brassai, in his book Conversations with Picasso, later accused of trying to separate from reality. “The Mathematician” quietly lampoons problem solvers in art, which can be read as a cop out. Importantly though, it questions the taboo of connection as intention. It posits, I believe, that the pursuit of a counter-intuitive or disconnected singularity misses the point. The wellspring of discovery, the riffing and experimentation that birthed the cubist movement was now lost to a burgeoning scramble for an art-formal zenith (i.e. what follows formally as a linear one-up progression).

Perhaps this is the most important effect of the Great War on the cubists, Rivera’s return to realism, to populist murals, his influence on artists, especially minority artists in the Americas, the WPA period in the USA, and his wife Frida. Artist Hale Woodruff studied with Diego Rivera for a year in 1938 before completing his seminal work “The Mutiny on the Amistad,” a piece about a slave revolt on the slaveship Amistad. Cinque, an African slave, the leader of the rebellion had had enough and acted on it. It’s a recurring theme in populist rhetoric, in some war propaganda: we’re fed up, you and I. You and I, we’ve certainly had enough.