The tortured artist is an archetype widely portrayed in popular culture. From the angsty, misunderstood art student, to the drug addled rock star, all the way up to Vincent Van Gogh and beyond, it often seems that the artist’s lot in life is misery. Frequently it appears that artists are hard up for cash, abstract or cerebral to a fault, and highly critical of themselves and others. So is the average artist doomed to agony from the start? The January show at Space 1026 confronts this melancholy, courtesy of Marissa Paternoster.

Needless suffering

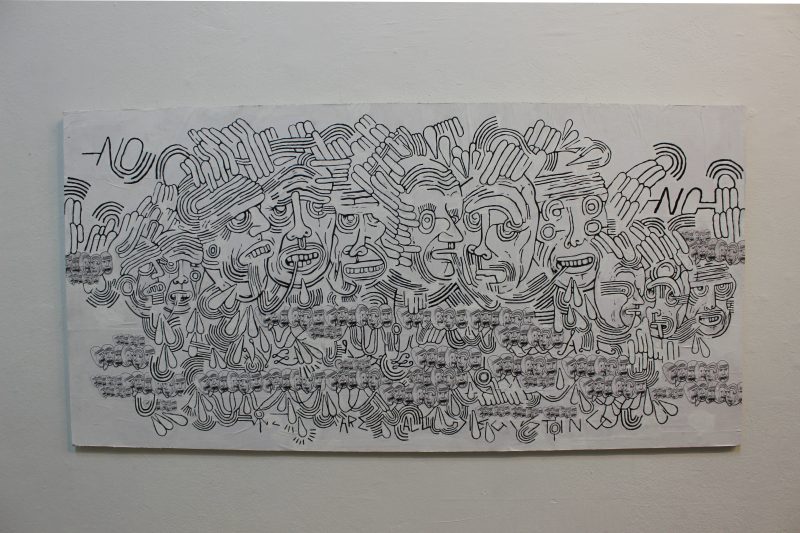

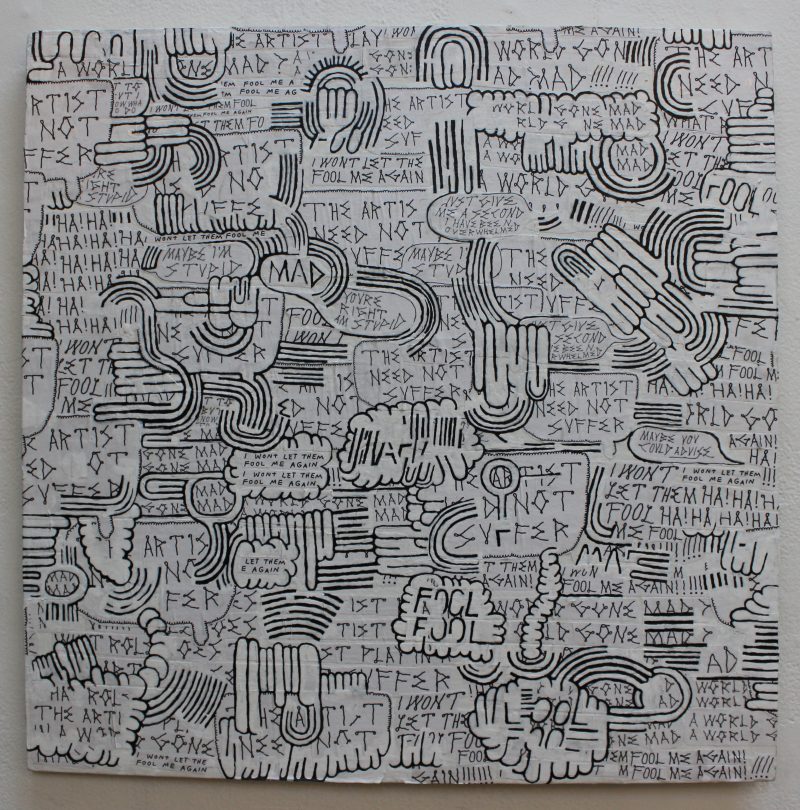

Entitled The Artist Need Not Suffer, the exhibition quickly forces you to wonder how tongue-in-cheek the title is. Paternoster’s work is an unsaturated foray into anxiety, self-doubt, introspection, and dissatisfaction with the human condition… all of which seems suspicious considering the title.

Color is entirely absent from the exhibit. In fact, so are shades of gray. The show consists of black and white mixed media canvases which feature heavy repetition, twisting illustrated linework, cartoon figures, thought bubbles, and handwritten text. In one corner of the gallery sits a bedroom “suite” where a bed lies next to an end table full of white pill bottles, each bottle painted with simply the word “NO.” The table on which the pill bottles rest reads “No more bad thoughts” in a similar fashion, painted around its base.

At the opening, the form of a person in a black hoodie laid prone and motionless on the bed, obscured by blankets. In order to see the details in the artwork blocked by the mattress, visitors had to crane over the sleeping figure, provoking a disconcerting feeling of intrusion and unwanted closeness. With no breathing apparent, it was safe to assume this was a prop put in place to generate just such hesitancy in the viewer. The fact of the matter is that Paternoster used the opening as an opportunity for a nap, and she remained covered and motionless throughout, ultimately forcing art viewers to invade her personal space.

Undercurrents

Besides this physical discomfort, however, we find ourselves submerged in the artist’s thoughts, where we discover a whole range of psychic anguish. Many of the pieces contain some variation of thought bubbles, implying their introspective origins; however, none of the pieces is designated with an actual title. In this sense, the artworks are more like manifestations of the same psychological undercurrent than standalone images.

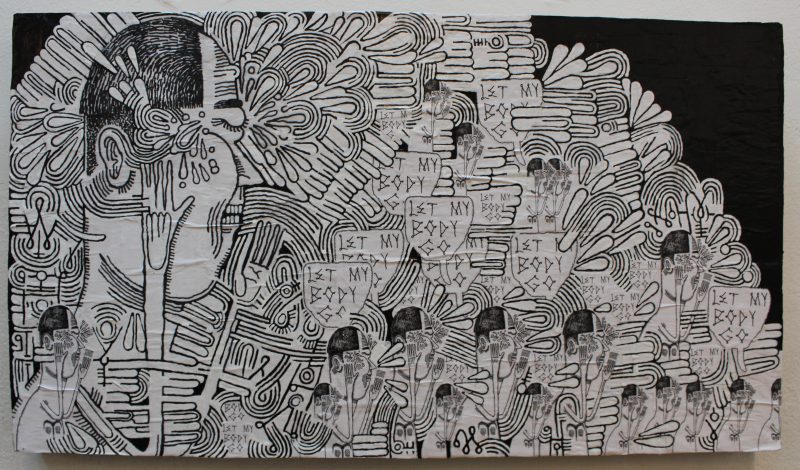

In one piece, we find a man with an abnormally large and precarious-looking head, his skinny arms flailing upward. Abstract linework explodes forth from his face, beginning as a spray of sweat or tears, and rushing away from him in a cavalcade of patterns. His likeness is repeated over a dozen times across the canvas in different sizes, and most of these repetitions are paired with speech bubbles reading, “LET MY BODY GO.”

Paternoster seems to reject dualism for a more holistic worldview, although this does not automatically translate to harmony. Elsewhere the text variously reads: “WORLD GONE MAD,” “WHY,” “I’M NO GOOD,” “FOOL,” and many others. By spilling these fears and criticisms onto canvas, Paternoster engages in a painful but honest dialogue with her audience. It is true that many artists struggle with these problems, but suffering is not at all an inherently artistic trait — it is a human trait.

Collective suffering

Although it would be near impossible to divine all of the themes and ideas pouring forth from Paternoster, she taps into the beneficial and harmful effects of prescription (and possibly illicit) drugs, the escapism of sleep, avoidance, death, abandonment, and self-esteem. Her characters are sullen and frail, and yet her titular profession that the artist ‘need not suffer’ remains the elephant in the room. Just because we need not suffer doesn’t mean we won’t or we don’t, suffering is merely independent from the creative process.

The times we live in are uncertain, unstable, and sometimes downright terrifying. In The Artist Need Not Suffer, Paternoster serves to reflect the madness of the world at large and tempers it with a burning inner turmoil. If there is any consolation here, it’s that misery supposedly loves company. Perhaps in collective suffering we may find joy or camaraderie. Perhaps not. Whatever the case may be, art–including Paternoster’s–is an outlet for, and not a captive of our pain.

The Artist Need Not Suffer is on view at Space 1026 through January 27, 2017.