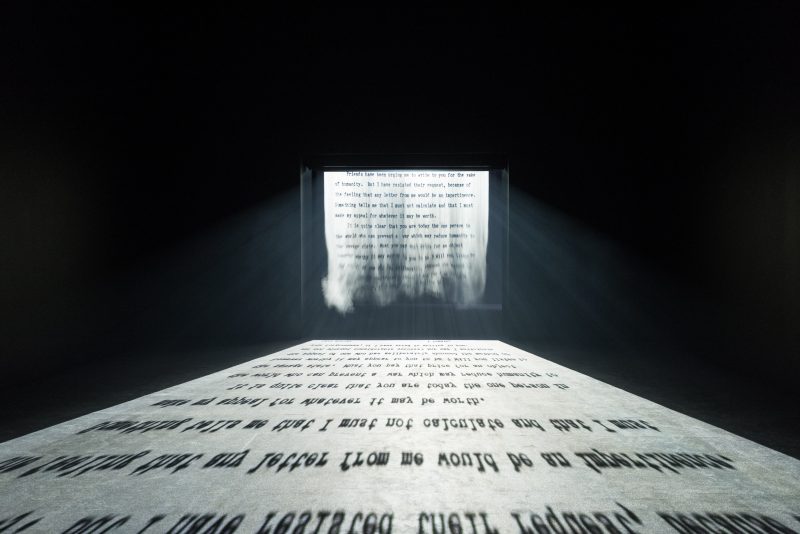

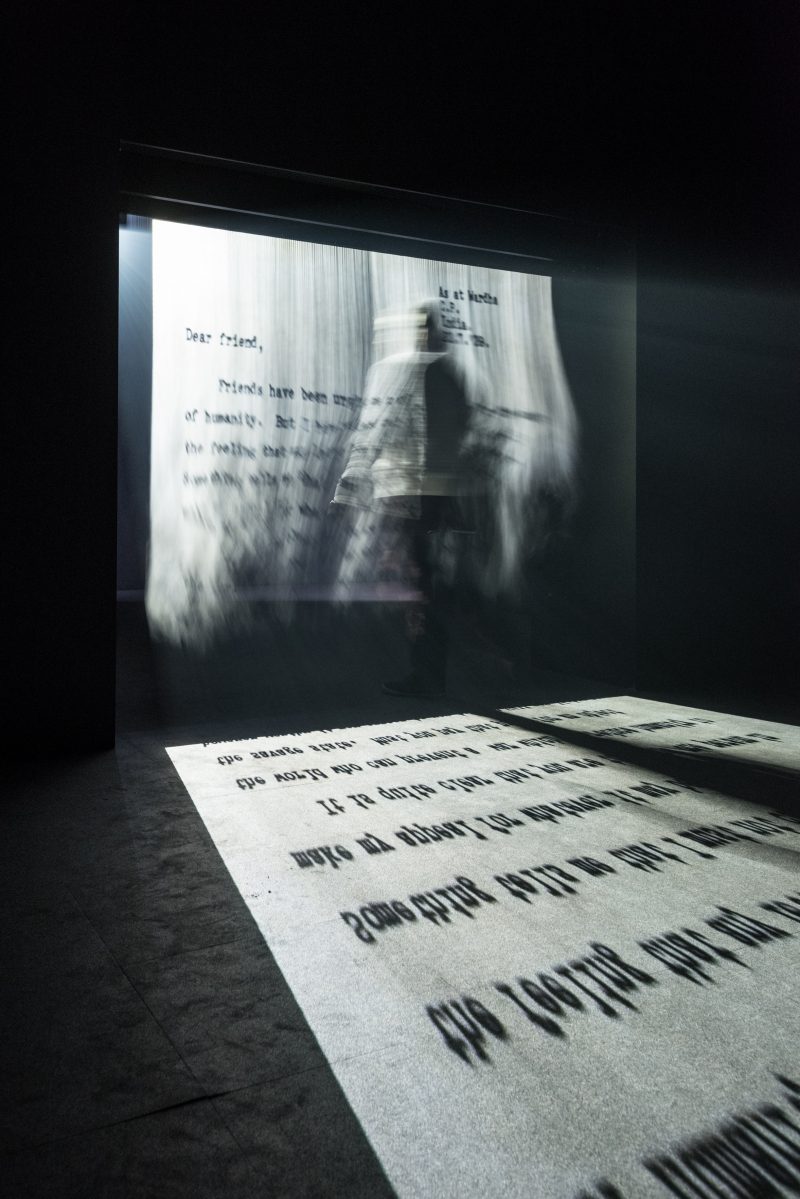

“Covering Letter” has soul, to be clear, rasa. Rasa—a sublime resonance. The finale of Jitish Kallat’s Public Notice series is a happening, a piece experienced more than a piece seen. A thick fog pours into a blackened room, backlit. A cascading mist is a backdrop for an urgent plea. What I see is like a reverse of the famous Star Wars intro. A green-tinged light is splayed onto a darkened floor, an elongated trapezoid, its widest base farthest away from the fog. Mahatma Gandhi’s 1939 appeal to Adolf Hitler ascends a wall of plummeting cloud over and over again. A voice rises. The English signifiers, a potent assemblage of characters are more legible the higher they traverse the vertical phenomenon. The hum of a fog machine is the only audible part of the show. Beneath me, a floor lit, too, by the only light in the room—a projector—the inverse of “Covering Letter” drifts to the back of the Julius Levy gallery. I’m nearly sickened by it, a physiological blindside, the pull of a backwards continuance. Individual streams of descending fog, together side-by-side resemble the culmination of a river flow, a drop. It’s a kind of performance piece, a video-less video art, a quasi-interactive postmodern anomaly. “Must you pay the price for an object…” Gandhi writes in his covering letter, a preface to a comprehensive one he wrote in 1940, one year later. Covering Letter is a passageway. I only discover this after I leave the exhibit and reenter a large bright hallway in the Perelman Building, a part of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The mist is a mask for a threshold, a room, a space to go on the other side of obfuscation, the fog of war. There’s an exit beyond the entryway. Perhaps this is the climax of Kallat’s piece, a viewer’s breach of a hidden passageway.

Looking within

It’s what Martin Heidegger talks about in his Essence of Truth, a book based on his lectures at the University of Freidburg in the early 30’s. What is that, that perceives beyond the readily accessible? Heidegger asks. He refers to it as a passageway, the organ or the part of the soul that senses in excess of the senses, or sensorial perception exhausted. Gandhi, in this vein, appeals to a second set of eyes within Hitler, something beyond conquest, radicalism and racial hierarchies, a kind of balance Paul Klee imbued in his compositions. Gandhi wished to steer Hitler away from the entrapment of binaries. There is a fulfillment beyond impotence and omnipotence, humiliation and a triumph. It’s ironic then that Heidegger, as scholarly and significant as he was, served as a high-ranking Nazi.

It’s also ironic that Hitler was a talented artist. In the traditional sense, he was a gifted naturalistic painter. I say ironic because there’s a kind of patience and maturity we attribute to fine artists, temperamentally furthest away from the iron-fisted rule of dictators. There’s Kandinsky’s theosophical belief about the artist existing at the tip of a humanistic pyramid, but generally speaking, visual artists are imagined to be low key. An artist once exclaimed to me, “Hitler was nice!” No, he wasn’t calling Hitler nice as in nice-nice, but sick with the paintbrush or pencil, a technically superb draftsman, a great renderer. Erich Fromm, a German psychologist, speculated that this was partly fueled by Hitler’s need to feel uniquely gifted—in high school he excelled at art only, the discipline he was naturally good at. In The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness, Fromm builds on the work of his predecessors, including a report by W. C. Langer written in 1943 for the OSS, a wartime precursor of the CIA. Both Fromm and Langer speculate about an intense oedipal complex within Hitler, but Fromm was less inclined as I am to attribute dark-magically abnormal qualities to Hitler.

This is the only problem I have with “Covering Letter;” at the surface, it continues the narrative of singularly powered men who accomplish the greatest of evils while a dumb society obeys. There were men like Heidegger who was singularly gifted in western thought, who essentially knew better but embraced Nazism. He does, however, leave clues to his developing ideas of morality when he says in The Essence of Truth “[Good] means: it is done! It is decided! It does not have any kind of moral meaning…” There was good, not as what ought to be, a value, or the Christian opposite of sinfulness, but that which makes something “good (suitable) for something, what can be put to use,” echoing Plato. There are ways to disrupt this artistically, to point to a kind of agency that exists within each citizen—beyond the edict. There are pathways beneath the crest of zeitgeist. President Obama talked about a “self-governance” in his farewell address. There is always the option of living while self-examining under a mighty wave, and maybe this is what Kallat ultimately implies with his passageway.

History lessons

And the lore of the rise of Hitler is there to deconstruct. Klara Hitler was a loved and respected homemaker. Fromm surmises that she was unhappy in the way that many German housewives were unhappy, without any extra-domestic opportunities. Alois Hitler was an authoritarian but an authoritarian in the same way most middle-class German fathers were authoritarian, so nothing out of the ordinary. Supposedly his last words before he died of a heart attack were “Those blacks!” But he was referring to “reactionary clericals,” Fromm suggests, not black people.

Hitler was normal but very determined and not very successful early on. He was a fan of cowboys and Indians—tales of American cowboys and Native Americans. He wanted to be an artist, but even more so an architect. He was rejected from art school, though, which may have destroyed a well-spring of narcissistic vigor inside of him. He served in the German military, but had never risen above the rank of corporal albeit highly decorated, he was political in the way that men are political, and he was jailed for it—for nine months, a kind of gestation period, where he worked on Mein Kampf. What Hitler possessed, though, was a voice—a unique ability to galvanize the populace. He had a voice that encapsulated German suffering and because of this he was discovered by the German elite. The early videos of his speeches seem like a kind of performance art—impossibly impassioned. But the Nazis he led caused real cataclysmic destruction. A scene from the documentary Shoah by Claude Lanzmann comes to mind, where a former Nazi describes with a tragic indifference, the systematic killing of Jews in Treblinka, a German Nazi camp in occupied Poland. He goes into great detail about the logistical inconvenience of ending many Jewish lives. Relativism notwithstanding, I think it’s good to think of the Holocaust as bad, and I think it’s good to think of Ghandi’s nonviolent triumph over England as good. The Dandi March was good. The Final Solution was bad.

What Kallat seeks to explore in “Covering Letter” is a near miss between two of the 20th century’s most influential minds. This juxtaposition of these two is a near-collision of worlds, east and west, right and wrong, peace and war. One had spoken and maybe one had listened. The viewer is left with this—what could have been, what could be.

Jitish Kallat’s “Covering Letter” is on view in the Perelman Building of the Philadelphia Museum of Art through March 5, 2017.