Sentimental violence

The two are dead, the two are hanging. The scene here is a backdrop nearly faded to white. The two men are an installation, a community project. A mob gathers to view, to pose–a communal sacrifice, a devil’s deed. The two are hanging as a reminder, a historical document of the early twentieth century. The piece entitled “Heirlooms and Accessories” (2002) is a triptych, three images of the same infamous scene–Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith are hanged by a mob. The piece is one of the first works you encounter in Kerry James Marshall’s retrospective Mastry, now showing at the Met Breuer.

In each piece, the face of an onlooker who stares back at the photographer is isolated, enlarged and framed as a keepsake, hanging from a necklace. They’re opaque against an afterthought, nearly invisible. The faces, three women, show a range of emotion from ambivalence to contentment. The piece evokes nostalgia, a romantic past. Marshall uses this sentiment as a kind of bait for what lies beneath, or in the background. Photos of hangings were once exchanged by postcard as a cultural mainstay, right there with the traveling circus and the county fair. This is quintessential Marshall, the research, the knowing, the visual sophistication. You get the feeling that very little is lost on Marshall and very much is considered when he makes each piece. Mastry reveals the entirety of Marshall’s genius–the range, spontaneity, and evolution of his work.

Old masters, new beauty

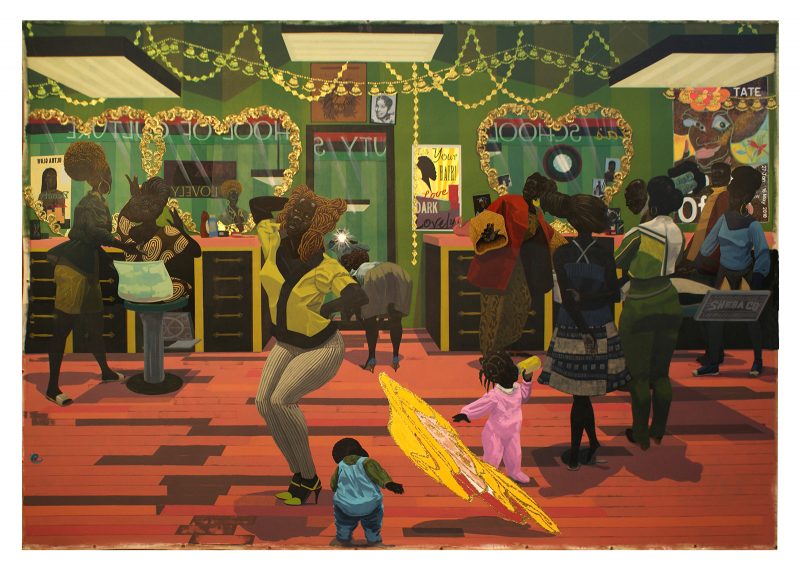

The influence of “the old masters,” as Marshall himself calls them is evident in visual juggernauts like “School of Beauty, School of Culture” (2012). The generously scaled piece is a collection of things to be seen instantaneously and things to digest later on. The off-centered foreground figure is a black woman, a woman literally painted black. Marshall normally uses the color black to paint black people only, and nothing else in his work. The woman is a diva in her mind. She poses like a 50’s starlet complete with blonde hair, that is, blonde locks, possibly a weave. She’s glamorous; in this setting, she is glamour. Below her, skewed and stylistically alien is the disembodied head of Sleeping Beauty, Disney’s princess. Only the little girl and boy that flank the apparition seem to notice its presence. The little girl who wears a pink onesie points at the anomaly with her pinkie and pointer fingers, while the little lad in blue inspects it. The illusion–Sleeping Beauty’s proportioned head can only be seen at certain angle–is a reference to Holbein’s “The Ambassadors,” which similarly employs a skewed skull. The beauty shop nonetheless is a mecca of ghetto chic, a mojo palace, a swag temple. The mirrors in “School of Beauty” are framed by large gold intertwined rococo hearts, which reflect among other things a room-length band of red, black, and green. This is where black liberation and black beautification meet. And though the romantic face of this piece gives way to poignant social commentary, you get the sense that Marhsall is having lots and lots of fun.

From the walls of color in his series that continue throughout the Breuer, to his earlier work, the oversized snapshots, the smaller pieces that take on death, black identity in America, and his deep, painfully humorous comics, Marshall is an artist who has worked and played his way into the all-important arts conversation. In one of his enlarged photos that adorns an entire wall in Mastry, the father, son, and the holy ghost—Kennedy, Kennedy, and King—are framed in gold and lit from behind. Photos of Malcolm X, four little girls, three civil rights workers, Emmett Till are added to the tally, tucked in between the photo and frame. So much of the intellectual and creative work accomplished by African-Americans is about retelling stories. Filling in. So much needs to be corrected, so much ground needs to be covered. Mastry is a great example of what the visual arts can add to this reconstructive work. For this reason, I think it’s about time a black visual artist becomes a household name in black homes. Black folk, meet Kerry James Marshall. He works for you!