On 2 January, British art critic John Berger died at age 90 in Antony, a suburb of Paris. His death coincided with the final weeks of La Trahison des Images (The Treachery of Images), the expansive Magritte exhibition at the Centre Pompidou. Berger was best known for Ways of Seeing, a radical book about how to look at art; required reading for most liberal arts students in the past 40 years, it was based on his innovative 1972 BBC series of the same name. The book and the series unpacked the hidden and not so hidden meanings of paintings and the act of looking. The cover famously reproduced René Magritte’s seminal work about the problem of representation, “The Key to Dreams.”*

Notoriously pairing school book objects–a horse’s head, a clock, a pitcher and a suitcase–with texts that undermine the images depicted (the clock is labelled “the wind,” for example), Magritte’s “The Key to Dreams” signaled the widening rift art and language. Magritte’s focus and the Surrealist creed was a full-throated grab at meaning and language itself, shaking the sense out it.

Word, image, meaning

Word and image rapidly became bi-polar nodes of consciousness at the onset of the 20th century, accelerated by the widespread use of the camera, mid-century world wars, a concurrent rise of popular science and psychology, and the breakdown of belief in almost every sphere. It was only logical that the notion of the thing and its name would be viewed as an essentially arbitrary relationship (according to Ferdinand de Saussure). Words are plastic; meaning and truth are subjective. But language–the ultimate man-made tool–reigns supreme in the truth business.

The Magritte show was a parade of the Belgian Surrealist’s masterworks, paintings that shaped a growing awareness of our willing deception and conflation of words and images, and effectively the problem of truth. The works illustrate how recognition and cognition work with and against one another, proving that the mind can maintain contradictory notions. It was a prescient period. Years later the labor of these works bore fruit: Berger’s book heralded (along with thinkers like Wittgenstein, Walter Benjamin, and more contemporary philosophers and semioticians) thousands of careers in the area of “interpretation” to comment on what others were looking at, reading, and building–and to perhaps tip the bucket toward one subjectivity over another.

In their work, both Magritte (1898–1967) and Berger bang up again and again against the stubbornness of the object–the idea of objective reality. Facts. What’s real, what’s not real, what is imagined, dreamed, and where essentially does truth nest and sleep? It’s an enduring and complex set of questions.

Seeing and meaning in a post-factual world

In remembering John Berger and making my way to the Pompidou’s gift and book shops, I had the chance to reread Ways of Seeing. It begins in a simple, compelling fashion: “Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognizes before it can speak.” Berger’s Ways of Seeing is, ultimately, an autopsy of “looking” and “seeing,” representation and reading–a treatise on making sense of reality’s surfaces. For the late art critic, looking was a choice and always performed in context (and in space and time). Looking is certainly the most powerfully ally of human “reality,” but Berger cautions that seeing and belief often suffer a cognitive disconnect.

While Magritte’s work has a directness to it absent in most modern and contemporary art, its discourse and prowess is often more provocative in its populist appeal and accessibility. Magritte’s surrealism, with its deft realist foundation, is often copied and widely parodied, and employed as a vehicle for a variety of present-day ideas.

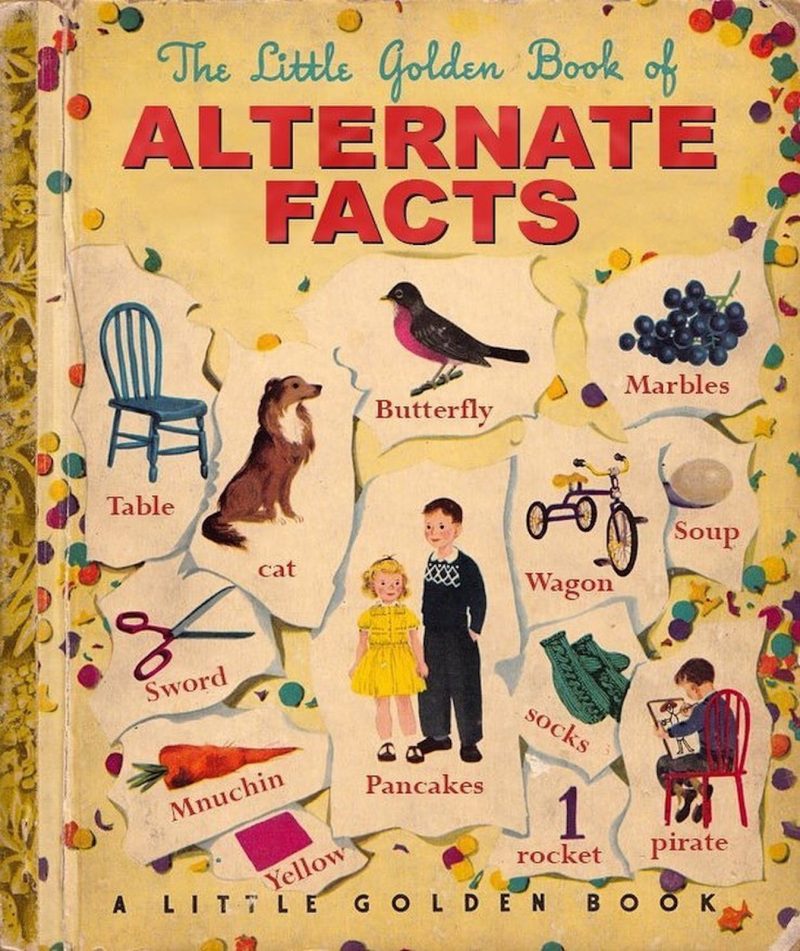

Case in point: A recent collage work by illustrator Tim O’Brien sends up Trump spokesperson’s now infamous “alternate facts” in a mocking, Magritte-informed school reader cover. The Little Golden Book of Alternate Facts features a bird labelled “butterfly,” a dog labelled “cat,” and a boy and girl labelled “Pancakes.” Like Magritte’s “Key to Dreams,” these images are child-friendly and the exercise is is an equation: image + word = facts. Of course it’s absurd–a kooky brand of 1984 Orwellian “double speak.” O’Brien’s work, while delightfully sarcastic, does have a sinister undertone in the media context of “alternate facts.”

Indeed, illogical tautologies stream from Magritte’s encyclopedia of the world, much like a child learning to talk. The absurdities that Magritte quietly broadcast are possible in this and any universe; meaning, one realizes, is ultimately in flux. But Berger and Magritte charge the viewer with the responsibility of working out the real, and ultimately that which is critical and consequential. How to do that, how to decode reality? Perhaps only with our greatest tool and its full arsenal of flavors: language. Language, which got us in trouble to begin with.

*”The Key of Dreams” is also called “La Clef des Songes,” and refers to the 1930 painting, which included different objects and words in French; the 1935 version in English is slightly different and appeared on John Berger’s book cover.

- Ways of Seeing / Penguin

- Pompidou Boutique

- René Magritte exhibition

- John Berger Ways of Seeing (BBC First episode)