On four nights in February, International House showed over sixty short films in a traveling Spanish animation film festival, From Doodles to Pixels: Over One Hundred Years of Spanish Animation. Organized into eight programs and encyclopedic in its scope and ambition, it was an animation marathon–delightful if a bit overwhelming.

Spain is not a country that I immediately associate with either historical or avant-garde animation, so I was curious–what is Spanish animation, and what makes it distinctly Spanish? Will these films be interesting for normal people who aren’t obsessed with Spain like I am, or will my boyfriend resent me for dragging him out to see obscure Spanish short animations on a Friday night?

After seeing six of the eight programs, which were organized roughly chronologically from the birth of Spanish animation in the first decade of the twentieth century, all the way to the most up-to-date digital animation produced within the past few years, I saw that people responded most enthusiastically to the contemporary shorts, especially the ones in English (obviously) or made by animators now working for the big American studios like Disney and Pixar. I enjoyed their technical skill, but I was most drawn to the shorts that seemed more foreign, less familiar, and that used the techniques and conventions of mainstream (often American) animation in a slightly off-kilter way.

Feminist focus

Paying attention to the credits throughout the series, I was struck by the active participation of women in all aspects of production, but only a handful of animations could be qualified as feminist. Given animation’s inherent ability to alter and distort physical reality, its techniques lend themselves to feminist explorations of the body. I loved Mercedes Gaspar’s 1995 Las partes de mí que te quieren son seres vacíos (The parts of me that love you are empty beings), which combines live action and stop motion animation to create a surreal dinner between a man and a woman who take each other’s words of love a little too literally. Gaspar grew up in Teruel, hometown of legendary filmmaker Luis Buñuel, who together with Salvador Dalí made the surrealist film, Un Chien Andalou, in 1929. Buñuel and Dalí’s film opens with a cringe-worthy episode of an eye being sliced with a razor blade, and Gaspar’s two lovers cut off successive body parts, including mouths and eyes, offering them to one another in a surreal dance of love and consumption.

Ghosts from the past

César Díaz Meléndez’s Zepo (2014, 3 minutes) uses avant-garde technology (including digital and old fashioned sand animation) to create a haunting, wordless vignette of violence and terror. A small child out gathering firewood in the woods comes across bright red blood stains in the white snow, and follows their tracks to a dying man, caught in a bear trap on the ice of a frozen lake. Terrified, she runs back into the woods and comes across a pair of Civil Guards, looming figures in black with their distinctive four-cornered hats. She pleads wordlessly for help and leads them back to the frozen lake and the dying man, but the story takes an even darker turn–the forces of law and order are not, it turns out, on the side of good.

The young girl reminded me of a character in a Spanish cinema classic that deals with the period immediately after the Civil War (1936-1939), in which a mysterious wounded man–presumably a rebel–is killed by the forces of the state. Díaz Meléndez’s sand animation using a muted palette of black, gray, ochre, red, and white sand is like nothing I had seen before. Here’s a demo video that shows Díaz Meléndez’s time-consuming process.

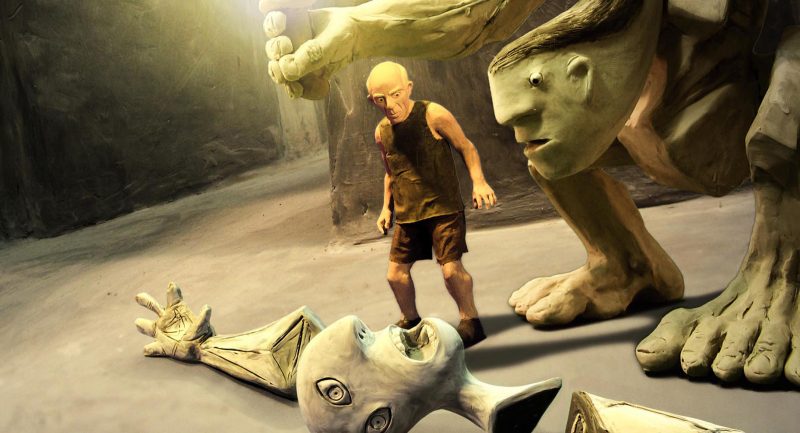

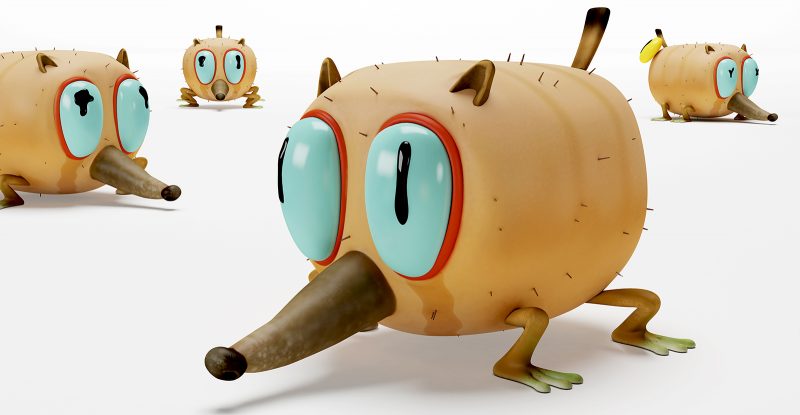

CGI send-ups

On the opposite end of the spectrum was Guillermo García Carsí’s Doomed (2011, 10 minutes). Billed as a “biological cartoon,” Doomed offers an affectionate and absurd send-up of the Richard Attenborough-style nature documentary. I loved the idea of an animated nature documentary, which seems like a contradiction in terms. García Carsí presents a series of imaginary evolutionarily challenged creatures, such as porcupines whose quills are internal rather than external, so that when the poor critters sneeze, they rupture their own organs and die immediately. Morbid, but hilarious–and totally the opposite of the indestructible cartoon bodies of Wyle E. Coyote, Donald Duck, or Bugs Bunny. With a stark white background, the smooth CGI bodies of these doomed creatures looked both hyperreal and impossibly surreal, and their antics kept me in stitches the whole ten minutes of the film. Unlike so much CGI that feels like a sterile display of technological prowess, García Carsí and his team of animators seem to be sending up the scientific pretensions of the medium.

At the end of the four days and eight programs, I’m not sure that all my questions about Spanish animation were answered. There’s certainly no innate Spanishness in any of these shorts, and what comes through is diversity and unevenness. But I think the collection as a whole has a lot to offer even the least Spain-obsessed viewer. If your idea of animation starts and ends with Looney Tunes, and with the hegemony of American production studios like Disney and Pixar, these shorts will be eye-opening.

If you didn’t catch From Doodles to Pixels at International House, you can purchase the DVD set on Amazon. Not all of the shorts shown in the traveling version of From Doodles to Pixels (shown here at International House, at New York’s MoMA, and at Miami’s Centro Cultural Español) appear on the DVDs, but they contain lots of new material, as well as an accompanying book with essays by curator Carolina López, who oversaw the entire project, as well as other scholars working in film and animation theory.