Shantrelle Lewis uses words like “superstition” “mojo” “storytelling” and “roots” to playfully introduce the show High John the Conqueror Ain’t Got Nothing On Me: American Hoodoo and Southern Black American-Centric Spiritual Ways at the new gallery, Rush Arts Philadelphia. The North Philadelphia gallery is owned and operated by Danny Simmons, who moved here from New York recently and co-founded the Rush Philanthropic Arts Foundation. Simmons is the primary curator of the exhibit, and he began curating the show when he first conceived of opening RAP.

Spirituality of Hoodoo

Hoodoo is serious in my estimation. And the exhibit of 13 artists, some local and some national, lives up to the puissance inherent in the practice of Hoodoo with a resplendent display of power and power objects. And in case you were wondering, High John the Conqueror is more than a root used in potions; and in African American folk tradition, he is the prince, trickster and the mediator between all the spirits, man and God.

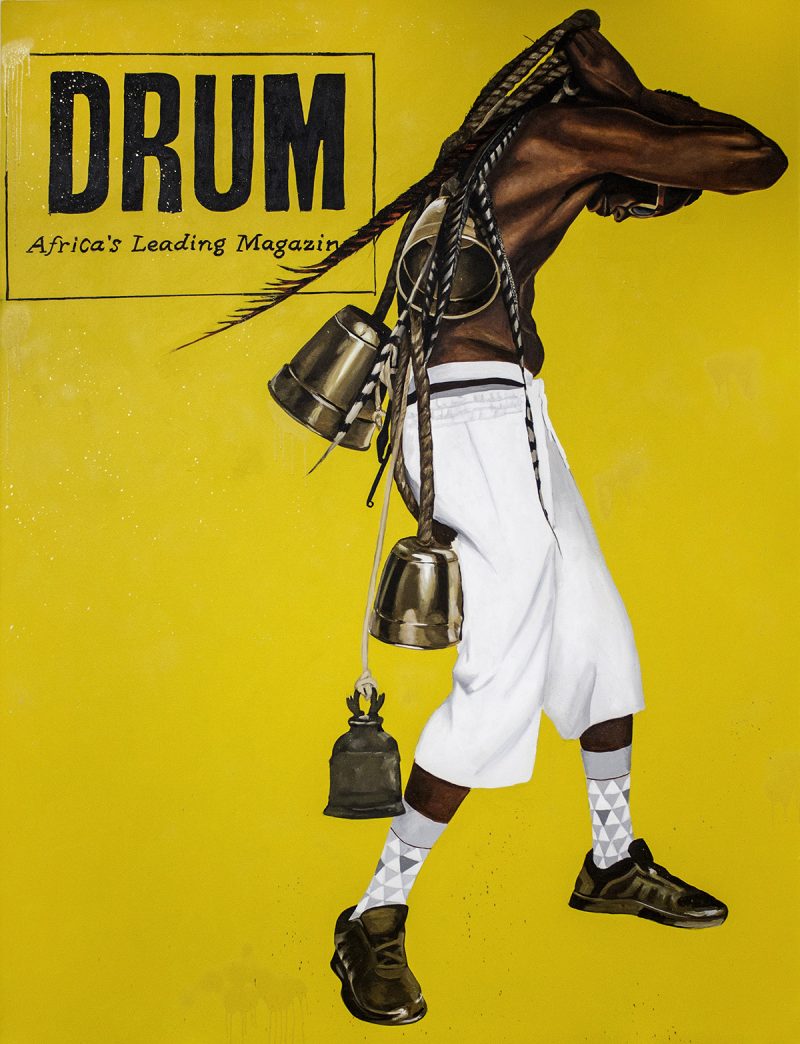

Fahamu Pecou’s self-portrait painting with his bare back to the audience is a forceful introduction to the issues of power in the exhibit. The work’s brilliant canary yellow background, the artist’s chocolate brown face in profile, and his white pants hung low like the B-boys — in many ways this is a typical Pecou image. He often casts himself in various situations and stances; his attire ranges from garb associated with hip-hop to the dandy.

Pecou spins off of magazine covers to create his paintings. In Many Rivers, he takes a layout from the important anti-Apartheid magazine of the 1950 and 60s, Drum Magazine, as a point of departure. Pecou appears slightly hunched, carrying a heavy load of jute rope and large-scale bells, with falcon feathers entwined, the latter, possibly a symbol of his spirit animal or guide. In traditional African cultures the drum is an essential communication tool; therefore, its implication here is all encompassing as a symbol of African retention by the artist.

Hoodoo’s relation to African practices

With an exhibit dubbed American Hoodoo, I can’t help but relate the works to ideas inherent in religious ideologies particular to West Africa and the Kongo, which have a relationship to Hoodoo practices in America.

Take Vanessa German’s black doll dressed in red and gold, that is dedicated to a deceased friend. Cascading from the eyes of the highly embellished doll are gold beads like tears.

Red and yellow are related to the religious practice of Ifa among the Yoruba of Nigeria. Whether the transliteration of German’s figure is the goddess Oshun, I am not sure. Oshun colors are yellow and gold; she is the Orisha of the rivers/fresh waters and of unconditional love, femininity and diplomacy.

German adheres to what Janet Kardon, art historian, once called the “aesthetic of excess,” in which every surface is encrusted with found materials. Like a votive God-head sitting on an altar to be worshipped and adored, the back of the German’s figure is surrounded by a fan-like ornate structure rendered in red and gold.

A High Priestess of Hoodoo

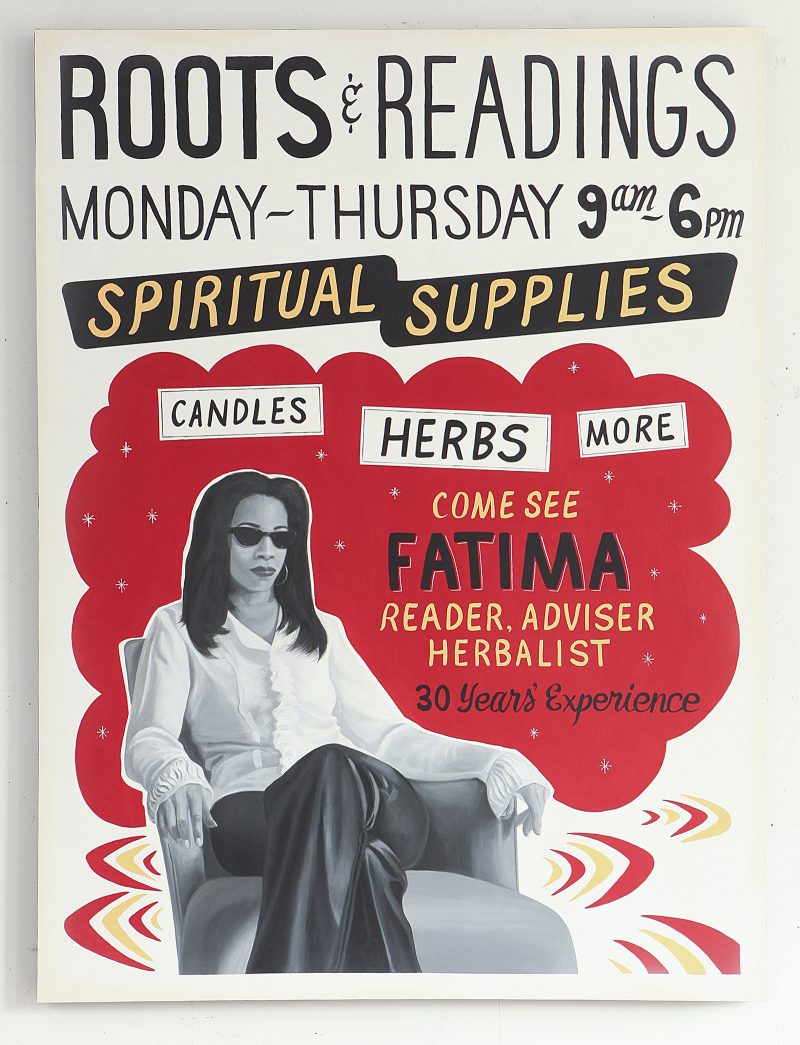

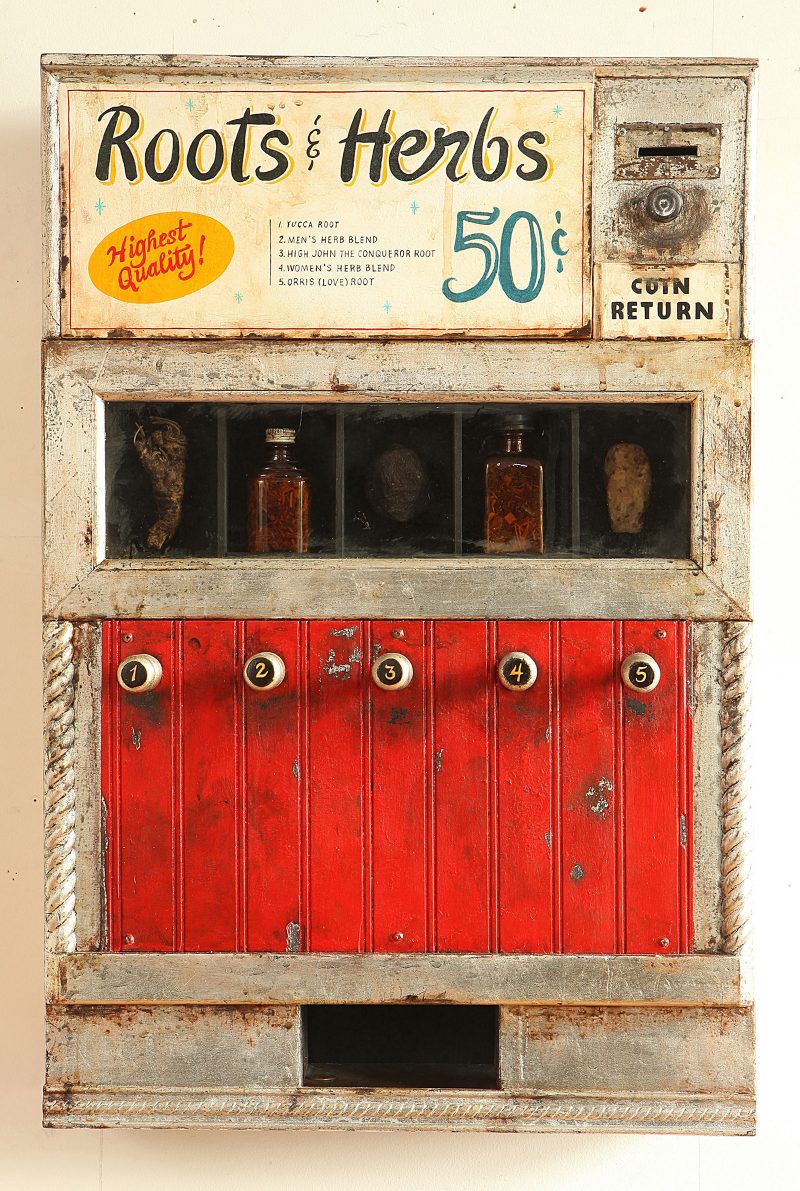

Renee Stout presents “Fatima,” her alter ego, a high priestess of Hoodoo. Fatima is part of a complex narrative, in which she functions as a healer and diviner. One piece of the narrative on view is a wooden plaque, advertising Fatima’s skills as a reader and another, The Root Dispenser, is a cabinet advertising herbs and roots for 50 cents, including yucca, orris and High John the Conquer roots and vials of men and women’s herb blends, essential in the practice of Hoodoo.

According to artist and historian, Keith Morrison, African American artists often work outside formalism and the mainstream to express themselves. And evident, in many instances, in this exhibit is the convergence of African retention, with fine art tenets and folk/outsider art. Self taught artist, Anthony Carlos Molden’s large relief painting is an example of this type of merging of sensibilities as is the sculpture of Kevin Sampson. Rife with a tumultuous movement of form and materials, Molden combines paint, fabric and objects to create a quasi-figurative piece; however, his painting could have been completely abstract and still retained its power.

Detox the Ghetto by Kevin Sampson — a sculpture that looks like a headdress that borrows heavily from the Gelede masking traditions of the Yoruba — has a face that is non-traditional in that there is no opening for the eyes or mouth and brings to mind the embellishments found on Congolese Kuba helmet masks. Sampson combines these sensibilities and in using found materials, beads, toys, wood, cement, acrylic paint makes this work uniquely his own. The title is borrowed from the Newark, NJ graffiti artist, Jerry Gant, who would sprawl “detox the ghetto” on buildings across the city.

Rewriting history in magical photographs

Fabiola Jean Louis’ excerpts from her Rewriting History series are haunting and dare I say beautiful. In her photographs, she poses black women of multiple hues in 19th century fancy dress seated or carefully posed surrounded by accouterments associated with black folk culture—a Caribbean styled black doll, a bejeweled N’kisi-derived inlay.

In one photograph, Madame Beauvoir ponders an iconic painting of a scar-whipped slave. The back of Beauvoir’s dress is embroidered with marks similar to those of the man depicted in the painting, as if she needs to remember the horror of slavery in contrast to her present state as a lady of leisure. An added dimension to the work is that not only does Louis stage these impeccable tableaus, but also the dresses, exacting in every detail, are made of paper.

Filled with images whose surface beauty belies their deep meaning, the show is a delight to ponder. Take a trip to the Logan neighborhood to catch a glimpse of an exhibit that is beyond sheer magic.

High John the Conqueror Ain’t Got Nothing On Me: American Hoodoo and Southern Black American-Centric Spiritual Ways is on view at Rush Arts, 4954 Old York Rd, until April 8, 2017.