The first signs of Yayoi Kusama were the red balloons and polka-dotted ground at the top of the escalator at L’Enfant Plaza. Then I spied a row of Jersey barriers covered with large, red polka dots and, crossing Independence Avenue, the dots continued on signage across an entire block leading to the grassy center of the Mall. Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors, at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture garden through May 14, before a national tour, lends itself to that sort of fair-like promotion. This should please the eighty-eight year old Japanese artist, who always had a flair for publicity and even hired a PR firm in 1967. Her work is a crowd-pleaser, and if visitors come away with the message that serious art can be fun, they will have gained something valuable.

And there are crowds in attendance, and often long lines, despite the fact that the museum is offering free, timed tickets to the exhibition. Visitors are limited to 20 seconds in each of the five mirrored environments that are the focus of the exhibition; while short, that’s longer than average museum visitors spend in front of most artworks. The timing resulted from discussions between the artist and curators. The work was clearly intended to be experienced at leisure, and this is a concession to the reality of museum presentation. The majority of visitors I saw were touring the exhibition with cameras, throwing away their chances to experience Kusama’s work properly; what the artist intended to be experiences of loss of the self became, instead, sites for souvenirs proclaiming “I was there.”

Fun is hardly the end point of Kusama’s work–merely a step along the road to the artist’s utopian, universalizing vision. She has explored the way in which perception contributes to our knowledge of self and the outside world, our understanding of the self in relation to others, the presence of death in life, and the relationship of human life to planet Earth and beyond. In her ideal world individuals would recognize their connection to and responsibility for each other and the environment, and appreciate the minuteness of our planet in relation to a limitless Universe.

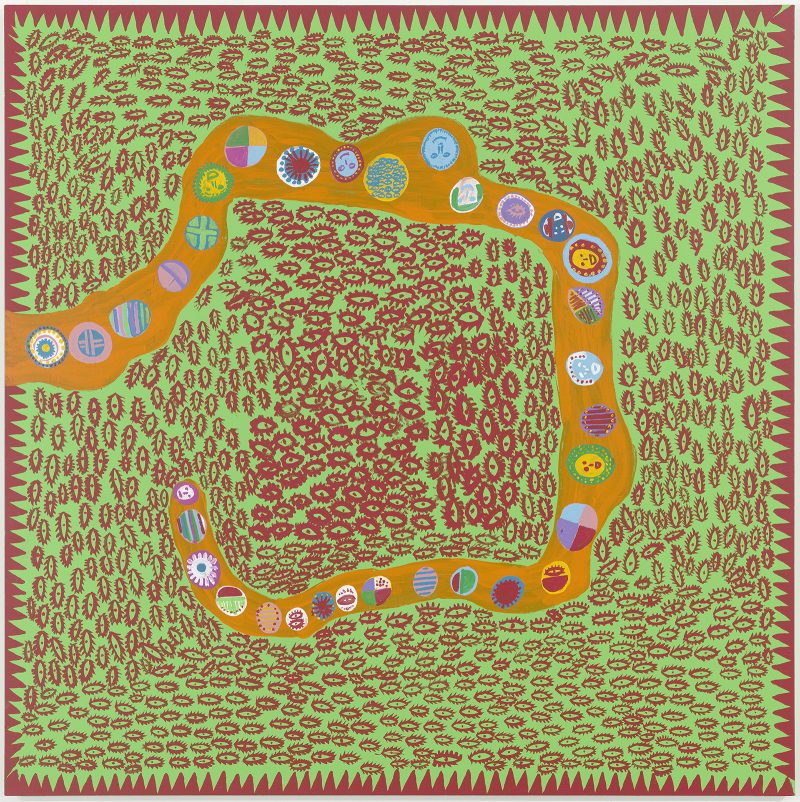

Photograph: QAGOMA Photography. © Yayoi Kusama.

Figure/ground zero

While including wonderful examples of her small watercolors and collages, large oil paintings with allover patterning, three-dimensional objects–reminiscent of Surrealism–covered entirely with phallic forms made of often polka-dotted fabric, sculptural groupings and installations, the Hirshhorn exhibition emphasizes the mirrored rooms and peep show boxes Kusama created, beginning in 1965. She made 20 of them, and the exhibition includes five rooms that visitors can enter and one mirrored peep show. Kusama speaks of her allover net paintings as exercises in figure/ground relations; she painted the ground element of the net, and the color seen through it, which is normally the ground, becomes the figure–or vice versa, depending on how one sees it. Her mirrored environments are three-dimensional figure/ground studies where the viewer is literally the figure, whose mirrored image disappears as it approaches the horizon of an infinitely-mirrored and receding ground.

Kusama worked in the midst of New York’s experimental art scene from 1965-1973 and had success there and even more in Europe; this was remarkable for a Japanese woman in a Western-centric period when women’s art was routinely ignored. She had tremendous drive and self-confidence, and her skillful use of publicity may have been a necessary offense, rather than a personal inclination. After returning to Japan in 1973 she continued to produce and exhibit, but largely dropped out of notice in the U.S. until 1989, with a solo exhibition in New York, followed by larger retrospectives in 1998 and 2011-12.

Kusama’s concerns were common to many of her contemporaries. Her early, allover net paintings were non-hierarchical and monochrome, reflecting a search for artistic ground zero after the devastation of WWII that was prevalent among artists in heavily-bombed Europe, and in Japan, with groups such as Gutai. Kusama was shown in European exhibitions with Piero Manzoni, Yves Klein, and members of both the German Zero and Dutch Nul groups. Her reduction of brushwork to small, repetitive actions reflected a rejection of the heroic, emotional brushwork of the Abstract Expressionists which was common for American painters of her generation.

Performing bodies

The mirrored environments also expressed common concerns. These illusory spaces, where the viewer loses herself within an infinite regress of three-dimensional space, relate to the same post-war trauma that made her paintings of interest to European artists and curators. The artist said she employed the repeated, phallic forms with which she covered objects as a way of dealing with her sexual anxieties. The therapeutic use of an enclosed chamber to deal with sexual problems, which could describe Kusama’s first room, “Infinity Mirror Room–Phalli’s Field” (1965), recalls the revival of interest in Wilhelm Reich and his orgone boxes. Burroughs and Kerouac both referred to them, and they were common enough that Woody Allen and Dusan Makavejev parodied them in films in the early 1970s. Kusama’s use of light to create spatial illusions was consistent with work by James Turrell and Robert Irwin. The sense of endless space beyond the horizon was explored by artists working in land art. And mirrors were used by Larry Bell, Joan Jonas, Lucas Samaras, Carolee Schneeman, Robert Smithson, and Andy Warhol, among others.

Kusama also created performances–by herself, but more often involving others–which became more public and political as a form of protest against the Vietnam War. Her performers interacted with objects Kusama had made and appeared covered in her signature polka dots. She arranged for the performances to be recorded in stills and on film, and had herself photographed within her mirrored environments. Use of the body as art and the photographic record of actions were central to the performance art of Eleanor Antin, Joan Jonas, Yoko Ono, Carolee Schneeman, Hannah Wilke, and others.

Dissolving the self

Perhaps the closest parallels to Kusama’s media-savyness and multi-sensory environments were Andy Warhol’s various “Exploding Plastic Inevitable” events of 1966-67, Gesamtkunstwerks of music with film and slide shows as well as changing environmental lighting, which started in NYC and toured nationally. This brings up a subject that the Hirshhorn’s presentation avoids–the broad use of mind-altering, recreational drugs. During the period Kusama worked in the US, life was conducted to a sound track of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” “Eight Miles High,” “Mr. Tambourine Man” and the like. I am not suggesting that drugs were behind Kusama’s work; she was known to take medications prescribed for depression and other mental illness that recurred, but those would have been to stabilize rather than expand ordinary consciousness. But the interest in pushing the boundaries of sensory experience that underlies Kusama’s work was widely pursued with marijuana, LSD, and other illicit drugs, some of which produced a sense of dissolving self and universal harmony.

I am not certain that many of the mirrored boxes are needed for an understanding of Kusama’s art, and if visitors only experience three, they can explore her range of sensory effects. “Infinity Mirror Room–Phalli’s Field” (1965, re-created in 2016) was her first; the viewer enters a brightly-lit, mirrored chamber where an installation of polka-dotted phalli are arranged on the floor like flower beds. The inclination is to look down at the sculpted forms, but don’t; use your 20 seconds to look up, beyond them and beyond your own reflection to the endless horizon. It provides an extraordinary sensation of melting into the landscape.

“Infinity Mirrored Room–The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away” (2013) creates an expanding environment of colored lights, like being suspended within an endless, urban night scene, and “Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity,” (2009) turns an environment of flickering lanterns into a rural night scene, where the viewer’s own form is invisible. It was inspired by the Japanese ceremony of floating lanterns on a river to guide ancestral spirits to their resting place, and has much of the magic of visiting a dark skies area and witnessing the umbrella of star cover that is forever lost to urbanites.

The sensational appeal of the mirrored rooms distracts most of the Hirshhorn’s visitors from the rest of the works, which offer lower-keyed experiences but will ultimately ensure the artist’s reputation. This is reinforced when the exhibition is experienced as a series of photo opportunities, with most of the time spent checking cellphone images. I am a fan of Kusama’s paintings–both the early watercolors, only a limited range of which are offered here, and the better-represented large oil paintings which have some of the hypnotic attraction of Agnes Martin’s calming, repetitious mark-making and color.

The Hirshhorn exhibition, curated by Mika Yoshitake, is serious and respectful of the artist, even if it overemphasizes the more spectacular work, and it accommodates an intimidating number of visitors with well thought-out and executed logistics. It offers those unfamiliar with Kusama an introduction to her world, and will undoubtedly leave everyone wanting more.