Loving Blackness

From the author: This exhibition deals with some heavy, but very important and politically relevant topics. Though I am no stranger to being culturally outside the American mainstream, as someone who is not part of the communities in discussion (Black and South Asian), my perspective only goes so far. I highly recommend reading the essay that inspired the show, “Loving Blackness as Political Resistance,” by bell hooks, further thoughts on ally-ship and the African American experience.

Loving Blackness, a group exhibition at Asian Arts Initiative, links the experiences and perspectives of African American and Asian communities, in solidarity. Organized by artist, community organizer, and curator Jaishri Abichandani, the show takes its name from a bell hooks essay, “Loving Blackness as Political Resistance”. Like the essay, Loving Blackness the show tackles some difficult questions about race in America.

The exhibition features provocative work from more than 20 artists. Several big names such as Dread Scott, Tomie Arai, and Shahzia Sikander are included alongside numerous artists from many stages in their careers. I had the opportunity to discuss the show with curator Jaishri Abichandani and artists Priyanka Dasgupta, Chad Marshall, and Indrani Nayar-Gall. I will mainly be discussing their work and perspectives here, but I highly recommend going to Asian Arts Initiative to see the show.

Asian and Black artists in conversation

When Asian Arts Initiative approached Jaishri asking her to curate a show around Asian communities in support of Black Lives Matter, she chose bell hooks’ “Loving Blackness as Political Resistance” essay as a jumping point. The curator told me she felt hooks’ political philosophy best framed her own ideas of solidarity with blackness, and she saw the exhibition as a good opportunity to put the work of Asian and Black artists in conversation.

As a woman of color, Jaishri feels most of the rights enjoyed by her (South Asian American) community were hard won after the African American community paved the way; Loving Blackness is her labor of love in recognition of that heartfelt belief.

Tar Baby

The sculpture “Tar Baby,” by husband and wife team Priyanka Dasgupta and Chad Marshall, is a life sized lacquered rendering of a black child that smiles peacefully while sitting on a gold lotus leaf; the use of the lotus and the baby’s tranquil expression evoke the image of a Hindu god. The child is covered with tattoo-like gold leaf markings that resemble designer Louis Vuitton’s logo, but are actually derived from the West African Mandinka culture; the markings reference not only the wealth of the Mali Empire, at one point said to be the richest in the world, but also the fact that Mandinka people made up a large proportion of those who were enslaved during the height of the Atlantic slave trade. The base of the sculpture is surrounded by piled wood charcoal, which represents the jobs of Indian sailors in the shipping industry who immigrated to America in the early 20th century, and who passed as black due to their skin tone at a time when immigration restrictions against Asians entering America were particularly strict.

A work infused with many layers of symbolism and historical reference, “Tar Baby” is part of a larger body of work Priyanka has been developing while researching this topic with the goal of disrupting the binary associated with “passing”, pushing against the notion that passing as white is a positive.

The piece is filled with irony. The irony of a tarred black baby whose body is now an icon of adoration, plays upon and subverts the religious iconography of Christianity, whose imagery for centuries has celebrated the agonies of the crucified Christ and other saints. The tattoos that reference ideas of commerce and desire recontextualize the baby as an object of desire or even an object of fetish.

Meant as an examination of the negative connotations Indians may have regarding their own blackness, which sometimes translates into prejudice against blacks, “Tar Baby” asks viewers to reality check their own prejudice against dark skin and to become aware of what it means to be black.

Words

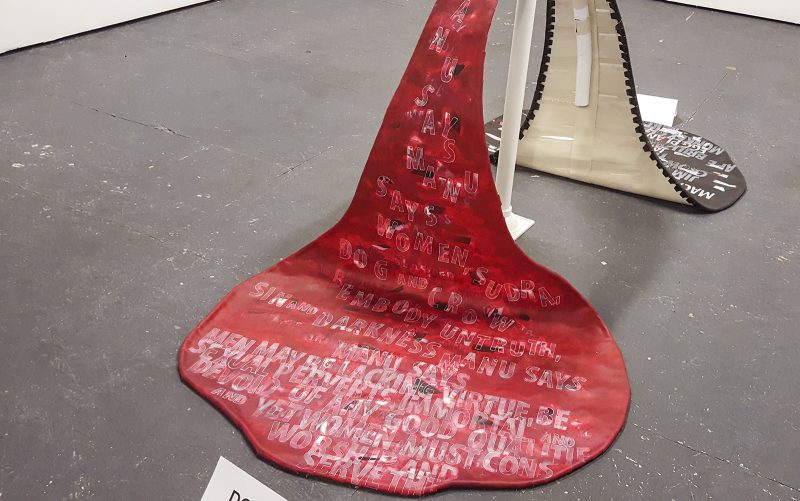

Commenting on the equivalent societal disdain and abuse heaped on African American men in this country and on people of the Dalit/untouchable caste in India, Indrani Nayar-Gall’s sculpture, “Words,” presents an allegorical narrative using a length of cut pvc pipe, with black and red fabric covered in words pooling out from either end representing the hardships faced by two groups of people, black boys and Dalit girls.

In the narrative piece, the black side is a multi-layered rendering of words, with names of African American men who died violently subsumed under a layer of derogatory terms attributed to them, such as thug and rapist. The piece suggests that the derogatory terms are used by some in society to justify the murders.

The red side presents more layered words, this time, in first-person stories from Dalit girls forced into prostitution and beaten, their genitals mutilated. On top of the stories’ words are excerpts from the Hindu scriptures about women, including the assertion that women, shudra (lower castes), crows, and dogs are embodiments of untruth.

Dalit women struggle every day with lack of agency, and illegal servitude continues in South India where young Dalit girls are sent into prostitution in the name of religion. Nayar-Gall has been telling the story of these girls through her art, and is currently working on a documentary film about them. Jaishri’s curatorial intention pushed Indrani to comment more on the parallels to the struggles of African American men, especially in terms of the justifications American and Indian society use to disenfranchise and mistreat these populations.

Indrani told me Loving Blackness is about understanding. Though others may not know without asking, she knows first-hand the anxiety of raising a black son in America. She believes sharing the narratives helps to foster understanding between South Asian and African communities, which continue to interact both in tension and solidarity.

Siddi quilts with African ancestry

The quilts known as kawandi are part of a cultural practice of the Siddi ethnic group in India. The Siddi are descended from African immigrants and have retained the quilting tradition. This is a thriving practice of a black community nearly unknown to the outside world. The colorful patchwork quilts are mainly made from well-used clothing, and recycled into an object used as a mattress and blanket. The parallels to the Alabama women quilters from Gees Bend, descendents of slaves, who are now-celebrated for their quilts made from recycled clothing and other cloth, is striking. (See the late Frank Bramblett’s personal reminiscence about Gees Bend.)

The quilts in the exhibition are products of the Siddi Women’s Quilting Cooperative, an organization Sarah Khan helped to found that produces and sells kawandi. The profits go towards communally-decided causes, such as purchasing school uniforms, or farm equipment, or paying medical expenses for those in need.

Concluding Thoughts

A poignant remark made by poet Mehrin (Mir) Masud Elias at Loving Blackness’s opening night put it well:

America sometimes feels like a domestically abusive lover. And, existentially speaking, you learn to hate yourself for going back for more. More beatings, more insults. And, for staying silent more often than not. As traumatized as some of us are, we are a nation that suffers from collective and selective amnesia.

Loving Blackness curator Abichandani emphasizes that people must discuss the problems within their communities as well as within mainstream America. Her goal was to make an exhibition that would be emotionally resonant with people, and I think she succeeded. She sees Loving Blackness as crucial, unconditional love: loving blackness itself not just as an abstract idea, but the actual people. Framing blackness in terms of love rather than anger, Jaishri believes all people of color in America owe African Americans so much for paving the way. She believes it is important to assert the positive associations of blackness in order to further the message of empowerment. She hopes that people will take away a feeling of love and respect – seeing black people as beautiful, powerful, strong, inspiring, and visionary.

Loving Blackness is on display at Asian Arts Initiative until April 21st.