In the protean 1980s art world, East Village “neo-expressionist” painter James Mathers appeared in a print ad handsomely paint-splattered promoting Rose’s Lime Juice, a cocktail mixer patented in 1867, after a formula to combat scurvy. His James-Dean-meets-Jackson-Pollock vibe provided the perfect cliché to connect the restless angst of downtown with the uptown vodka gimlet crowd. It was the beginning of a medium cool trend.

One would think successful visual artists, so steeped in image making, would be adept at making advertisements, or at least appearing in them but with a couple exceptions, very few living artists make it as the face of a commercial brand.

Andy Warhol, who, during his lifetime appeared in Polaroid, Sony, GAP, and other product ads, is the exception to the rule. Andy was good at business and he knew keeping his face (brand) in the public eye would help his prices. He also rubbed shoulders with Hollywood and Iranian monarchs and the frisson of celebrity hung around him turning him into a globally-recognized personality.

Where are all the artist pitchmen?

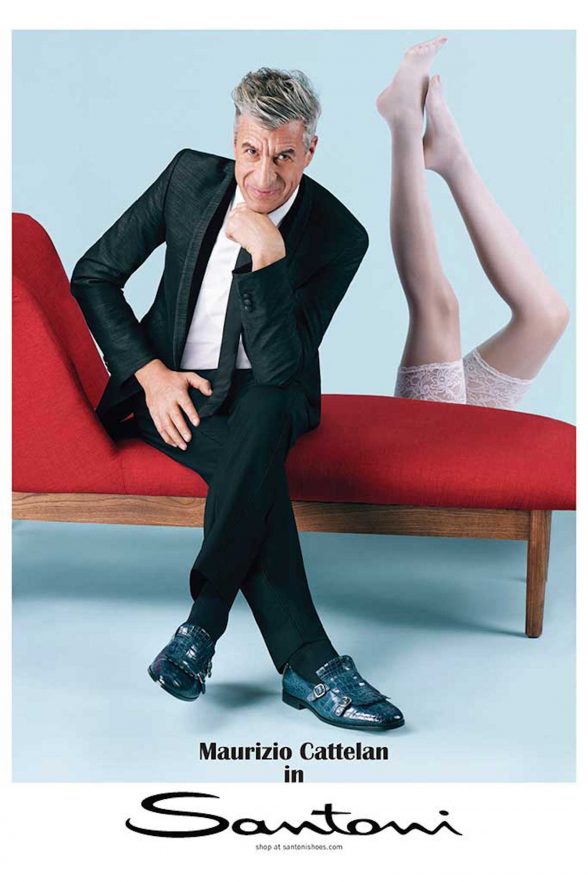

I was reminded of the dearth of artist pitchmen while leafing through French weekly, L’Express. The fashion supplement “Styles” featured a one-page ad for uber-expensive Santoni shoes, with–surprise!–the 56-year old art prankster Maurizio Cattelan. The Italian artist smirks at the camera as a pair of a woman’s legs angle upwards behind him; his shoes shimmer perfectly. It’s all very conservative, though. And his name appears on the ad to remind us who he is! Perhaps more recognizable for his golden toilet, “America,” or his “La Nona Ora (The Ninth Hour),” in which a life-sized effigy of Pope John Paul II is struck down by a meteor, Cattelan revels in the marriage of art and commerce. He produced surreal ads for Kenzo, and only last summer laid it on thick with kitschy window displays for Galeries Lafayette here in Paris, working under the moniker, Toiletpaper.

Art if not artists appear in ads – a little history

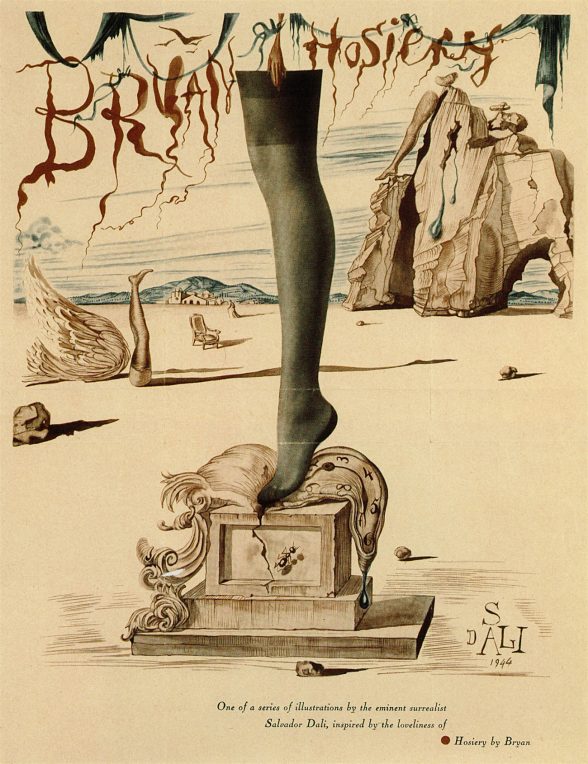

Artists whose works have become icons or even clichés in the wider culture can register in the global consciousness and their works can wind up in advertising–Magritte, Dali, Picasso, Warhol, da Vinci, Munch, Van Gogh, Norman Rockwell, and probably Grant Wood, thanks to his “American Gothic.” One should note that many of these artists are identified by one or two works. And, note that they are dead.

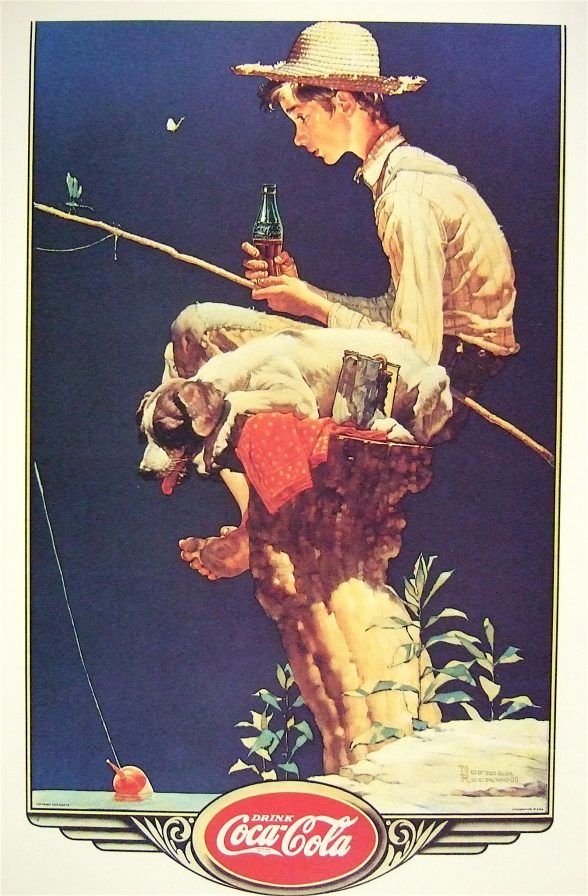

Dali produced women’s hosiery ads in 1944; Norman Rockwell illustrated Coca-Cola ads in the 1940s, Damien Hirst made Beck Beer polka dot labels in 1997, and for more than 50 years wine maker Mouton Rothschild used artist-designed labels for their Grand Cru bordeaux.

In the 1980s, Absolut Vodka was able to persuade creatives to join a campaign, perhaps taking a cue from Rose’s Lime Juice. Warhol, Keith Haring, Arman, and dozens of artists were invited to both promote themselves and the vodka in a multi-decade long print ad campaign. It put Absolut in the very cool category, and artists enjoyed the unique exposure. Drinking and art making have always seemed to go together.

Like Warhol, Haring seemed a natural for this. His first splash as an artist was pasting black paper over New York City subway adverts and drawing in white chalk his own icon-loaded messages. In addition to Absolut ads, Haring designed Swatch Watches (now highly sought after), ads for Coca-Cola, and Baby Bumpkins bibs.

More recently, Takashi Murakami was more directed in merging of his art and personality with commerce. The Japanese Pop master partnered with luxury goods maker Louis Vuitton, branding a multi-million dollar business in editions of handbags, scarves, toys, and wall paper, all very popular with jet-setting starlets.

Artist appropriations of advertising in art

Then there’s the case of artists using commercial brands in their work, conflating their own art brand with what’s sold in grocery stores. Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup paintings and Brillo Box sculptures were re-labelled product displacements. Some of Warhol’s last works cannibalized his own style, and were essentially corporate logos, like his ad for Apple Macintosh, or stand-alone art works like a silkscreen painting of the Paramount films logo.

Richard Prince took the Marlboro’s cowboy print ads to a new place–ads without text or products–but that was appropriation/alteration art. Ron English’s playful turn at reworking ads acidly lampooned Camel, McDonald’s, and other brand icons. English, in fact, has turned himself into a brand, he told me, having already produced limited editions for Converse Sneakers, prints for Newcastle Brown Ale, and labels for a new strain of marijuana. English claimed he will work with an advertiser “only if I believe in the brand. No Hummer ads!”

Artists say “No” to putting their face into an ad

But while iconic art passed muster for some risk-taking brands, few artists were tapped to star in print or television ads. New York-based painter Marilyn Minter said to me in an email: “It’s a long story… we get asked [to be in ads] and mostly we say ‘No.’” Paris-based artist Joseph Nechvatal said he wouldn’t do it regardless. “I object to the idea of appearing in advertisements on aesthetic grounds,” he wrote me in an email, “not ethical ones!”

Stuart Elliott, New York Times advertising columnist, says this of the dearth of artists in ads, “I think it’s not more common because a lot of artists probably see endorsement deals as a “sellout.’ Unlike, say, musicians, who used to eschew ad appearances or licensing their music but changed their minds once the music business changed and suddenly realized appearing in ads could help generate attention for their music,” he went on in a recent email to me.

Making money outside of the typical fare artists offer–paintings, drawings, sculptures, objects, books, prints, lectures, teaching gigs–is weirdly frowned upon. Or it might be the case that most artists, either by face or name, aren’t well known enough, pretty enough, or cunning enough.

“Warhol, of course, was big in ads,” said Elliott. “He did a Braniff airlines commercial in the late 1960s or early 1970s, paired with Sonny Liston I believe! And Ed Ruscha was here and there in ads in the 1980s.” But again, an artist in an ad remains a rare bird.

“You would think the mystique, the creativity, of artists would be qualities that Madison Avenue would want to glom on to and capitalize on,” added Elliott. “And if semi-known singers, performers, designers appear in ads, why not artists?”

Elliott told me in the email that while watching the television game show Jeopardy recently, the correct response to an answer was the question “Who is David Hockney?” None of the three contestants got it, he said. “So that is a big barrier, I believe, for using artists in ads aimed at a wider public.”

Jeff Koons like Warhol embraces the commercial

If there is an artist who truly embraces brands and art making, it’s Jeff Koons. Savvy and endlessly pitching himself, he has endorsed a number of products (but no vacuum cleaners, which he actually used in his early art). He recently designed a polished resin Venus fertility symbol bottle holder for French champagne maker Dom Pérignon; the special edition of 650 sell for $20,000 each. Koons appears in the promotions, pitching himself with his goofy Colgate smile. But Koons–a celebrity of sorts–is rich, not hip. Koons, a Cattelan contemporary, embodies geeky ruthlessness that comes with financial success, something that appeals to those in the market for $20K bottle holders.

Making art doesn’t always mean making a living, and the commercial world for better or worse does yield more exposure and better wages. It helps if you’ve produced at least one iconic work of art, or have a signature style that is worth imitating. And maybe to be young, but who knows for sure? To star in an advertisement, to be the face of a brand–even if you’re not a pretty one–an artist has to be recognizable beyond his or her art work. In that category, though, there really aren’t many who qualify, and those that do, don’t seem very inspiring. Most are just working on their own brands.