Haverford College’s Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery has a history of presenting exhibitions that push the viewer to confront social and environmental issues, from natural disasters to deteriorating infrastructure and political strife. Their latest show, Resistance After Nature, is no exception. Showcasing work by a diverse group of artists and activists whose contributions do more than just encourage critical thought; they inspire activism beyond the gallery walls.

Art, activism, and the environment

How can art and activism work together to address ecological collapse and encourage environmental progress? There’s no easy answer, but Resistance After Nature offers a few jumping off points. First, diversity is central to any call to arms for environmental change. Feminist, anti-colonialist, and pro-Indigenous ideologies are the backbone of this exhibition and act as the driving narrative throughout. Nine out of the thirteen individual artists represented are women, and the remainder of the works by collectives or research groups back their vocal support with action.

Second, a purely aesthetic statement often isn’t enough. Rather than precious art objects, the work here acts more like material evidence of outside efforts. Not to discount the power of visual art in a time of conflict but rather build upon it and work side by side with it, the projects asks us to roll up our sleeves and get to work.

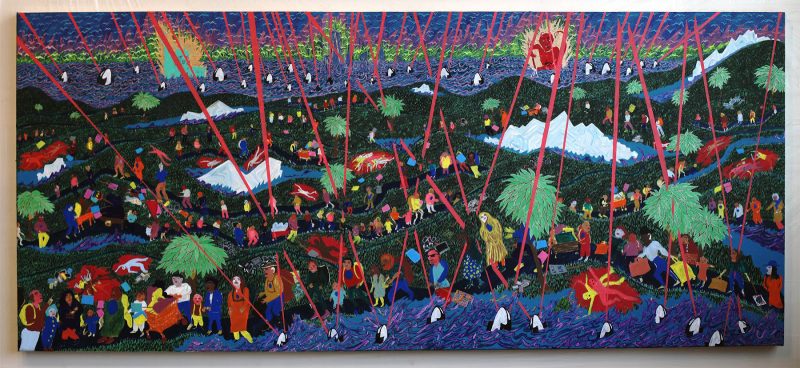

Haley Hughes’ arresting painting “Climate Refugees NYC” is the first piece to grab the eye upon entering the gallery. Her work is the most strictly visual component in the overarching activism of Resistance After Nature, but is a powerful signifier of the stability that a cared-for environment provides and the transience of one in crisis. The pseudo-apocalyptic scene reminds us that we have no home but the one we inhabit, and that self-made climate catastrophe renders us all homeless.

Two other works in the first gallery are especially recent–first, a row of “mirror shields” made and used by individuals protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) in Standing Rock, ND, presented by Cannupa Hanksa Luger, who is of Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Lakota, Austrian, and Norwegian descent and grew up in Standing Rock. Next to these, a video titled “We Are In Crisis” by collective WINTER COUNT takes the viewer on a slow, meditative aerial journey by drone over the landscape central to the DAPL. Washes of pale green and brown blend into one another, accentuated by the occasional intrusion of a road or incomplete pipeline, a reminder of the serenity of this place and the sanctity of the land at risk. The violence endured in resistance and the calmness of the land in crisis are powerfully at odds with one another.

Wasting our resources, consuming the planet

Mary Mattingly’s images concerning the mineral cobalt, a material of some value to the US government and an catalyst for colonialist extraction mostly in Central Africa, include hyper detailed photographs of the glistening material itself alongside images of extraction sites. In the center of the room, she’s worked with Haverford students to create bundles of material containing cobalt, the precious material itself invisible in the crumpled consumable products of daily life. The visual to material connection implies we are all complicit in the dismantling of natural resources for the convenience of consumable goods.

Another project by Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research (CLEAR), a feminist marine science and technology lab, takes a similar visual-material approach to the effects wasteful consumerism has on our environment. The project specifically focuses on plastic pollution in the marine ecosystem, which occurs in such small sizes (often marine plastic is smaller than a grain of rice) that it is overlooked by the human eye. CLEAR allows us to see them in great detail by displaying high resolution microscopic image of the particles, the actual samples of which are displayed in glass vessels directly below their blown up image. What is harmless or indiscreet to the naked eye can in fact be an indicator of massive negative trends for wildlife of all kinds.

Video work plays a large role in the exhibition, from Tanya Lukin Linklater’s piece “Water,” wherein she draws attention to the fact that First Nations lack access to clean water through dance and movement, to Ursula Biemann’s video “Forest Law,” which explores legal challenges (and occasionally victories) faced by indigenous communities threatened by colonialist interests.

“Forest Law” was especially affecting, as the directors lead us through communities in the Ecuadorian Amazon which thrive when left to their own devices in their native lands rather than being forced to adapt to what a larger power deems they need for improved quality of life, or in the interest of big oil and mining operations. This concerns all aspects of life, from humans to flora and fauna. For instance, it is estimated that there are approximately 350,000 species of flowering plants on Earth, of which 300,000 have been discovered and named. Of the remaining 50,000, Ecuador is believed to contain an enormous number. For botanists working in the Amazon, every day is a race against time.

While the past may already be written, the future is ours to compose. This is what exhibition curators Kendra Sullivan and Dylan Gauthier want viewers to remember when they leave the gallery and get back to their daily lives. We can all pay more attention to underrepresented communities and support their efforts to conserve our home and to find a way out, and we can all find ways to remain active in the fight. “We may not be able to exit the maze the way we came in,” they say, but we can find a way out with our own logic and determination.

Resistance After Nature is on view at Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery at Haverford College until April 28, 2017.