Steam irons

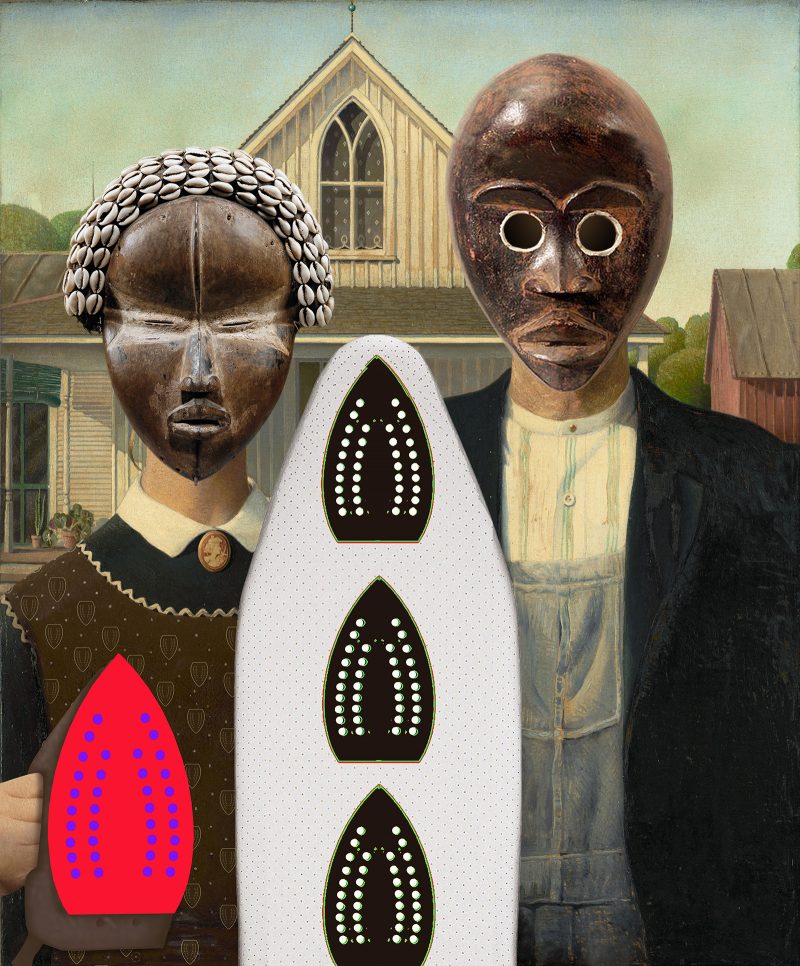

Grant Wood’s iconic “American Gothic” (1930) has, over the years, been adapted for many purposes–artistic, parodic, comedic, commercial.

In Willie Cole’s rendition of the work, called “American Domestic,” the pitchfork is replaced with an ironing board (of sorts–perhaps symbolizing a slave ship), the female figure is holding a red steam iron and her hair is replaced by cowrie shells, and both figures’ heads are replaced by forbidding African masks–the male’s with rounded hollows for eyes, and the female’s with thin slits for eyes.

The work, included in Willie Cole: On Site, at Penn’s Arthur Ross Gallery, is striking, but the message is difficult to discern. Cole is known as an African American artist inspired by West African religion, and his work based on steam irons is said to suggest the domestic roles of women of color as well as the Yoruba god of iron and war, Ogun. I think at least it is fair to say that this piece makes a powerful statement about a black reality overlooked in Wood’s classic depiction of the dour and severe middle American.

There are two other steam iron pieces displayed in the exhibition in which wooden planks are burnt, scorched by irons. One of them is pictured here. There is a way in which they are suggestive of diagrams of slave ships, packed with their human cargo. Earlier, similar works by Cole were slightly more mask-like–the two displayed in this exhibit are more abstract. All of the pieces in this series, however, powerfully evoke images of the violence imposed upon blacks in the era of slavery, and beyond. Branding irons, of course, tragically, were commonly used by slave owners in America to mark their human “property.”

Ladies’ shoes

You can buy a pair of Christian Louboutin high heel shoes for a few thousand dollars. Or you can go to the Salvation Army warehouse, as Willie Cole did many years ago, and buy cartloads of used ladies’ high heel shoes for about fifty cents a pound. Remember Imelda Marcos, and the scandal that erupted when, after her husband was deposed, over 1,000 pairs of shoes were found in her closet at a time when many Filipinos could not afford even one pair?

Well, Willie Cole’s stash added up to far more than 1,000, perhaps into the millions, he said when he spoke at the exhibition opening, and he became famous for turning them into materials for his art, as you can see in this show. There’s a loveseat constructed of them, African-like masks, and flat presentations composed of them which mimic works on canvas– perhaps a parody of high art minimalism and abstraction, perhaps not.

This work reflects a degree of formalism and style that you do not usually associate with Western found object sculpture, although it is close to the work of African found object sculptors like El Anatsui and Olanréwaju Tejuoso (recently featured at the Village of Arts and Humanities).

I probably would not have guessed this, but at his talk it became quite clear that Cole’s obsession with ladies’ shoes is related primarily to his fascination with women and fashion, particularly with women. The gallery notes about the exhibit connect his interest in these collected items to the individuals who once wore them, even to their “souls.” In his talk, he suggested the same thing. I wasn’t convinced.

The work is highly decorative, technically impressive, and it stands on its own. However, perhaps with the exception of some of the masks made from shoes, it lacks the emotional impact of Cole’s steam iron pieces, which are tied directly to the African American experience. Cole may be making a statement about our consumer culture, but I think that he misses an opportunity in this series to suggest the objectification, subjugation, and exploitation of women (black or white) by the white male patriarchy.

Plastic water bottles

On Site also includes a series of wall pieces constructed of a frame into which have been inset hundreds of bottoms-up crushed and painted plastic water bottles, reminiscent of Cole’s wall presentations made of shoes.

Cole clearly is interested in water as a symbolic life force. However, it seemed to me that beyond repurposing plastic bottles, he could be making a stronger statement about the devastating effects of these discarded materials on the environment.

Overhanging the gallery is a colossal twenty-foot chandelier constructed of plastic water bottles. Embedded in each bottle is a small figure representing a black man killed by the police. As a work of art, the piece, which was created by Cole, staff and students at the David C. Driskell Center for the Study of the Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora at the University of Maryland, is less impressive than Cole’s works made of shoes, because the craftsmanship, which is stunning in the shoe pieces, is missing in this community-made piece. The political statement it makes, however, is far more powerful.

Overall, the exhibition presents a remarkable, innovative use of found objects (Cole also works with hair dryers, telephones, and other objects), reminiscent of the work of Romuald Hazoumè, the well-known artist from the Republic of Bénin, and, of course, is part of a long tradition of work by the likes of Duchamp, Picasso, John Chamberlain, Andy Warhol, Isa Genzken, and Moustaphe Dimé. Hyperallergic’s Hrag Vartanian said it just right: “Finding beauty in the commonplace—some may even say banal—is one of artist Willie Cole’s strengths. His ability to rejigger the consumer world around us into something more fantastic creates the illusion that his art springs from the mystical intersection of folk culture, utility, design, contemporary art, and mythology.”

In his talk, Cole described how his work proceeded from word play and free association. He also proclaimed a philosophy of life related to “oneness,” noting: “Everything is anything and anything is everything.” He also said, “I just make stuff. I play.” Indeed, he does, and he does that masterfully.

Willie Cole: On Site was curated by Dorit Yaron and Curlee R. Holton of the David C. Driskell Center. The exhibition consists of 19 three-dimensional works created by Cole between 2006 and 2016, and will be open through July 2nd at the Arthur Ross Gallery. Shoe Box Recycling, an organization that provides shoes to people in need around the world, is participating in the exhibit, and visitors are encouraged to bring and contribute a pair of gently used shoes. Be sure to bring along some shoes with you to donate when you visit.