Over a quarter of Philadelphia’s population lives below the poverty line. Trek up Kensington Ave. in Northeast Philly, and the consequences are in plain sight. This neighborhood’s landscape of dilapidated buildings and spent syringes is the backdrop for photographer Jeffrey Stockbridge’s project Kensington Blues, a book and accompanying exhibition at Savery Gallery that gives a voice to people written off by poverty, addiction and abuse.

Stockbridge spent the better part of the last decade working his way around Kensington with his 4×5 large format camera and sifting through countless hours of audio-recorded conversations with neighborhood residents. When he was just starting the project in 2008 he drove all over the neighborhood, “too scared to get out of the car,” drawing the attention of those on every corner looking to turn a trick. Clearly the wrong way to go about his envisioned portrait project, he continued his journey on foot. He had nowhere to hide, and that was exactly the point — to make himself as vulnerable as the people who would become his subjects.

Stockbridge’s approach pays dividends, and as a result Kensington Blues is more than just a photo book. Most portraits are accompanied by a transcribed conversation the photographer had with the subject–sometimes the subject talks about how they got into heroin and clawed their way out, other times about the darkness that consumes their life. The conversations give the portraits context, both within the Kensington community and outside of the stigma of their addiction. While filled with photographic documentation of the streets and people, more than anything, the book is a work of oral history.

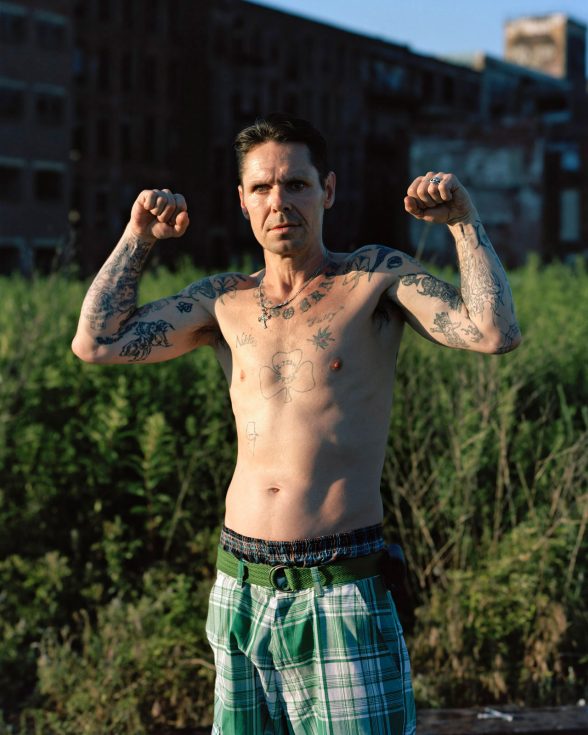

“There are certain stories that take precedence over the pictures. I had to find a way to alternate between,” Stockbridge told me when I interviewed him earlier this month. “There’s this photograph of Diana and her kids, she’s talking about how hard it is to raise them. Go right from this photo of them to a photo of these three guys, the D-street guys, Bobby, Danny, and Tor..flexing, posing on the train tracks. Look at this poor woman trying to raise her kids and then look at these grown men acting like boys.”

“Ultimately I’m trying to tell a story. If one person gets one connection that’s the same as the one I had making the book, I’ll consider it a success. I’m not the one to tell you what to get out of it, I’d butcher it if I tried. The book is the language.”

Individual stories illuminate communal blight

Take Mary, who’s spent the last twenty-odd years as an addict with the exception of an 8-year period of sobriety. She talks about the catch-22 of relapsing and having a child: “I can’t be with him because I’m on drugs, but I’m on drugs because I can’t be with him.” Her goal is to kick the habit and save up some money so she can get out of Kensington as soon as possible. She’ll be 42 soon–she first started on the street at 13.

Then there’s Bobby. Stockbridge says “I have a photo of Bobby in the show. He just got out of jail and immediately connected with his old D-street buddies. He was all hyped, talking about the good old days. I didn’t see him for a while and then bumped into him again a few years later. He was totally fading out. I sat with him again, he told me his whole story. He didn’t even know who his kids were.”

Vulnerability leads to accessibility

Stockbridge’s portraits of these marginalized people are surprising in their simplicity. The photographer opened up to his subjects and they opened up to him, and the pictures impart familiarity and empathy. They’re direct but still sensitive, like a friend who knows you messed up but doesn’t judge you for it. “Everyone always has choices they can make, but sometimes you only have so many choices at your disposal,” the artist says. I ask him whether the tone of the project has anything to do with the slow set up time and serious look of the large format camera. “Absolutely.” He said. I don’t think I would have been able to make any of those photographs if I didn’t have that camera.” It slows down the interaction and puts people at ease. “Don’t worry, I’m not gonna steal your photo and run off…I can’t…” he jokes in the book’s epilogue.

It also helped that he carried around photographs of people he’d photographed in the past. ”It definitely helped the project take off, because people saw photographs of people that they knew … they were like, ‘You’re photographing all these other people, you gotta photograph me! I’m part of this story, I’m part of Kensington!’ It became about self-worth,” he says.

Stockbridge kept a blog with pictures and interviews throughout the project. “I’ve got thousands of photographs, hours of audio. The blog became helpful since it allowed me to organize it and step back from it a little bit,” he says. There’s a lot of material on the blog that isn’t in the book, so it’s very much worth a visit to the Kensington Blues website.

Drawing a decade of work to a close

The accompanying exhibition at Savery Gallery offers a chance for viewers to immerse themselves in the artist’s Kensington experience. I could tell from our conversation how much the artist wants people to to see the giant prints mounted almost larger than life on the walls. The most powerful moment in the exhibition comes in a gallery alcove, where the walls are hung with small framed portraits placed right up against one another, totally engulfing the room. In the middle sits a record pressed with Stockbridge’s field recorded interviews, which the viewer is invited to listen to with headphones provided. Tuning everything else out, the effect is inundating. It’s almost like being there.

The project is unpretentious–but Stockbridge’s quiet documentation is anything but cold. He’s made something deeply empathetic. “This exists, this is happening and this is how I see it. The feeling of hope, that these aren’t bad people, that’s the full story…to understand the state of mind of people on the Avenue.”