You might not expect to see three profound art installations in a space with paint peeling from the walls amid ancient debris. That is, unless they are on view in the prison cells and cellblocks of Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, the 142 year-old, 11-acre grounds and decommissioned prison at 2027 Fairmount Ave. The new 2017 site-specific exhibits, which include Unconquerable Soul by artists Piotr Szyhalski and Richard Shelton, Hakims’s Tale by Erik Ruin and Gelsey Bell, and Sepulture by Jared Scott Owen, are presented with 11 returning art installations in cells on various cellblocks.

Escape through a skylight

Artists Piotr Szyhalski and Richard Shelton realized both shared a past history in prisons, prior to working as professors at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. Szyhalski, a native of Poland, spent his childhood visiting Polish prisons, where his mother worked as a nurse, and his father supervised a machine shop. And Shelton taught eight years inside Minnesota prisons, immediately after graduate school. So when Eastern State Penitentiary requested proposals for new exhibits for 2017, Szyhalski immediately called his friend of 23 years, now an administrator at Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles, to work on a project. The result is Unconquerable Soul, a technical yet metaphysical masterpiece in Cellblock 9, Cell 46.

The two artists arrived last summer to check out their location then debated how they could incorporate its unique features in their installation. They focused on the narrow rectangular skylight, which prison architect John Haviland called the “Eye of God,” implying that a prisoner could repent for his sins in solitary confinement, a theory later disproved and abandoned in prison reform.

The two artists discussed how they could transcend the space technically, yet keep with Haviland’s original intention for the cell. Thus, they used their skills operating drones, video, audio, animation, photography, and design to transcend space and time in an installation unique to the cell.

Voila! If you stand in the forlorn decrepit space looking into an overhead three-by-five foot two-way mirror, soon the sight-line changes from looking at your face to seeing the roof of prison floating away as if your soul escaped through the skylight and is floating towards the heavens. As the ascension is taking place, an audio plays the voices of reciting 27 different poems from eras contemporary to ancient, in various languages. The cadence of spoken words sound like prayers said in a religious setting, a church, mosque, or synagogue. The audio component lends another layer of spirituality to the unusual installation.

The poems are available on the prison website.

————————————————

A harrowing tale

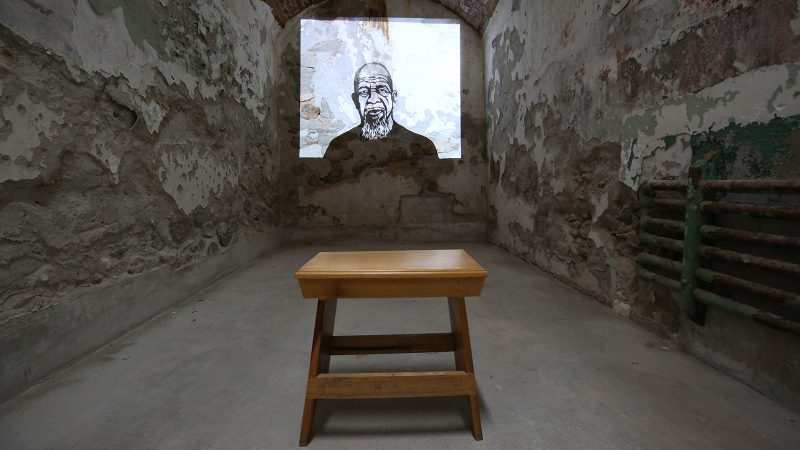

Hakim’s Tale is an eerie audio-video installation by artists Erik Ruin and Gelsey Bell in which Hakim Ali, a member of the 1960s-era Revolutionary Action Movement, describes how he survived 2 1/2 years of solitary confinement in what he described as a “boxcar.” In a four and a half-minute videotape loop, shown on a wall in Cellblock 6, Cell 65, Ali–whose radical movement combined the ideologies of, Marx, Lenin, Mao, and Malcolm X–describes his desperation in solitary and how “Literally, I lost it.”

“I had contact with nobody,“ he says, as parts of his video image breaks off and disappears from the wall. His meals were slipped silently through a slot in a prison door. “Nobody knew whether I was alive or dead,” he says. “I withdrew into silence. You know you should be talking to someone, a chaplain or someone… But you go into a world hard to describe, where you feel safe.”

In an attempt to maintain a sense of sanity, the Muslim says he began to pray to Allah for understanding, and that finally, “It registered that I needed to change what I was doing.” As he talks about finding himself through prayer, pieces of his image on the wall come back together to form his original portrait. In solitary confinement, he says, there are a lot of suicides because [prisoners] “just lose themselves. It makes no sense to nobody.”

Now 74, Ali lives in West Philadelphia and has been working for prison reform ever since he was released from a correctional center. His account of surviving without human contact was part of a much larger traveling installation on solitary confinement, but this concise edited version makes a powerful statement about how solitary can destroy the psyche and sense of self.

Otherworldly goods

In an installation called Sepulture, artist Jared Scott Owens pays tribute to his childhood hero Larry Davis, an “urban legend” in an era of crack cocaine in the Bronx. Davis was a drug dealer who took on dirty cops–yet paid dearly later when he was murdered in prison with a nine-inch shank in 2008.

Owens says he and his friends looked up to his hero, but never met him in the inner-city neighborhood plagued with drugs and dirty cops who stole drugs, gave them to rival dealers to sell, then, demanded a cut of the proceeds.

Inside Cell 30 on Cellblock 11, Owens’ installation reimagines what Davis would need in the afterlife. He carved an Egyptian-like sarcophagus, painting Davis’ face on a King Tut-like head at one end of the wooden coffin. He engraved hieroglyphs on the top and sides of the coffin. At the foot of the top of the coffin, the artist gouged images of Davis’ favorite things–a gun, crack vials, and knives–into the wooden surface. Nearby in a corner are memorabilia which Owens gilded–knives, a razor blade, a Walkman, a microwave–that he imagines that Davis would want to take to the afterlife.

Owens also found cassette tapes of music from Davis’ era, that he might like to listen to in the afterlife–hip hop, soul, funk, blues, and R&B by singers Freddie Jackson, Patti LaBelle, and Steve Arrington. The artist placed the cassettes in a special wood box that Owens made when he himself was serving more than 18 years in a New York state prison. Yet, in the last seven years of his sentence, Owens turned his life around. He began to read Blick publications on how to use materials to make art, at the same time he scoured any art publications that he could find to read about artists.

Now, Owens sees himself as a vessel for interpreting others. On a large wood plank, Owens engraved a portrait of Davis sitting in his wheelchair, surrounded by Egyptian deities, including Osiris, the god of the underworld and afterlife, and his sister Isis, who helped resurrect him after he was murdered. The wooden portrait leans against the wall at the head of the coffin. It is as much a portrait of Davis as it is a totem to Owens who turned his life around by finding inner peace through self-expression.

The three new commissioned installations at ESP were funded with proceeds from the prison’s annual Halloween tour, “Terror Behind the Walls,” and by a grant from the Pew Center for Art and Heritage, and funding from the Pennsylvania Council of the Arts and the federal National Endowment for the Arts. Also worthy of note, a new thought-provoking exhibit at the Penitentiary, “Prisons Today: Questions in the Age of Mass Incarceration” recently won the American Alliance of Museums’ highest honor, the 2017 Excellence in Exhibitions award. More information here.

Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, 2027 Fairmount Ave. Philadelphia, PA 19130. Open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Daily.