British-born, Pittsburgh-based artist Lenka Clayton recently completed a nearly three year residency at the Fabric Workshop and Museum. Her resulting show, Object Temporarily Removed, presents two new community projects, “Sculpture for the Blind, by the Blind” and “Unanswered Letter,” both based on her research into an object in the Philadelphia Museum of Art collection–Constantin Brancusi’s “Sculpture for the Blind.”

It’s hard to be playful and serious at the same time but Clayton’s two massive, time-consuming, community-based projects and her other works on view at the museum achieve the right balance of play and gravity and raise important questions about the audience for art and about art’s market value versus its intrinsic value.

Whose vision?

Clayton came across “Sculpture for the Blind” on display at the PMA. The Brancusi piece is a carved marble egg placed in a glass vitrine, making it not touchable, and thus not really “for the blind.” The artist was fascinated by the apparent contradiction of putting anything intended for the blind behind glass and it inspired her to create true sculptures for the blind, made by the blind. The Fabric Workshop and Museum facilitated two workshops to do that, one with the Overbrook School for the Blind, and one with Allen’s Lane Art Center’s sculpture class for the blind and visually impaired.

The visually impaired artists were read a long-winded description of “Sculpture for the Blind,” and afterwards they carved their own versions of the sculpture out of a large slab of plaster cast for their use. In total, seventeen of these new sculptures for the blind by the blind are on display, open for touching.

The white, vaguely egg-shaped sculptures are a lesson in how interpretation of words can vary wildly from person to person. The sculptures sit, row after row, in a grid formation at the back of the cavernous gallery. The midday light from the room’s large windows makes the brilliant whiteness of the army of eggs almost blinding. Each egg sits proudly on its own pedestal presented as an object of value. A few feet away sits a binder full of color photos of the artists holding their creations. The photos put distinct faces and personalities to the multitude. Most of the artists look very solemn cradling their artworks. The array of sculptures is inspiring, giving representation to artists that typically are not considered in gallery situations. “Sculpture for the Blind, By the Blind” touches on issues of representation and accessibility in the arts, as well as the malleability of interpretation.

Unanswerable questions

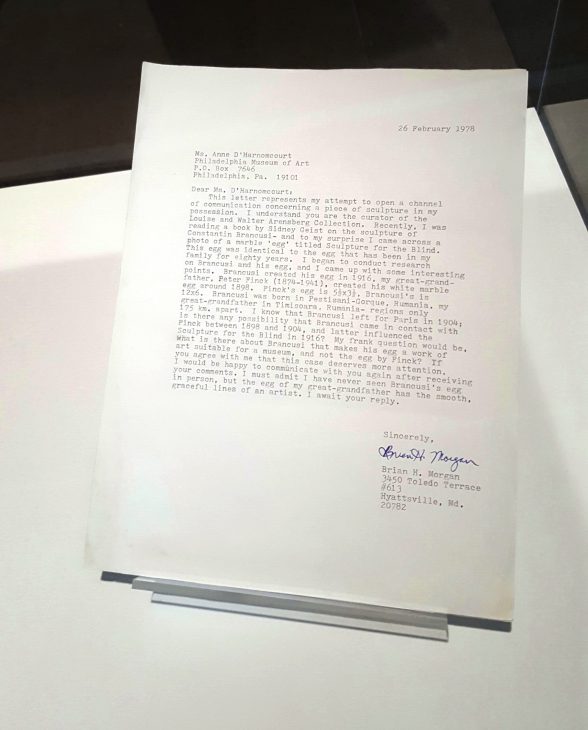

Searching the archives of the PMA for information on Brancusi, Clayton stumbled on a letter written in 1978 to the then-curator of 20th century art, the late, legendary Anne D’Harnoncourt. The letter writer posed a question that has been puzzled over and argued for as long as art has been an industry–why does one artist become famous and another, not?

Brian Morgan explained in his typewritten letter that his great-grandfather, like Brancusi, was a Romanian artist and made an egg shaped sculpture very similar to “Sculpture for the Blind” several years earlier than Brancusi’s egg; he asked the curator if it was possible that Brancusi was inspired by his great-grandfather’s sculpture, and inquired as to why his great-grandfather’s art was forgotten by time while Brancusi’s is remembered, and had a major impact on modern art. Forty years later, the letter has never been answered.

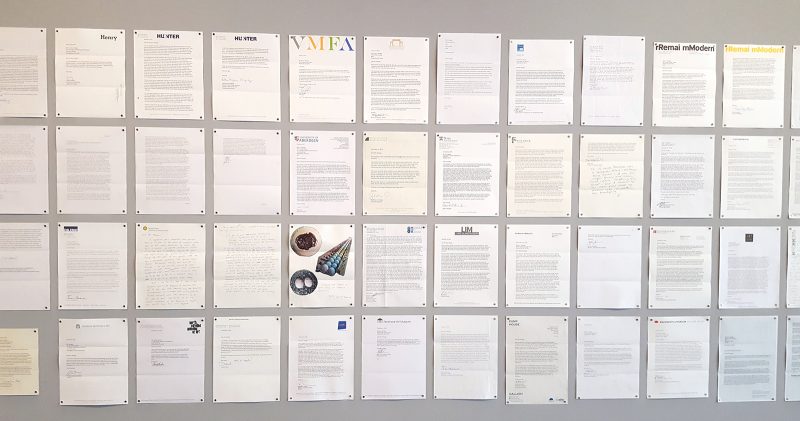

Clayton sent copies of the unanswered letter to over 1,000 arts institutions, curators, and professionals around the world asking them to answer Brian Morgan’s questions, and she received 179 replies, which are displayed on the wall of the FWM. Some of the replies include prominent voices from the Philly art world, such as John Ollman, Rob Blackson, and Ingrid Schaffner (formerly at ICA, now at the Carnegie Museum organizing the next Carnegie International). The replies range from sarcastic and condescending, to philosophical, to words of encouragement. Several institutions offered to display Morgan’s great-grandfather’s sculpture. The letters themselves are far from identical–while many are written on institutional letterhead, a large number are handwritten on colored paper and looseleaf; several include photos (including a newspaper clipping about Sculpture for the Blind), and one was simply a sheet of printer paper with a magazine collage of egg photos. Trying to read them all in one go is a bit of a lost cause, but the assemblage is enough to get the gears turning in your head–why does one artist become famous, while most others will never make it? Some of the replies talk about grand ideas like talent and genius, but most say it comes down to luck. No real surprise there.

Modern-day mysteries aside, “Unanswered Letter” raises some very good points. In the modern, oversaturated art world, who decides what constitutes good art? In a situation where two unrelated artists are making very similar works, who is qualified to say which is better? Is talent a real attribute, or does the focus on innate ability (talent, genius) trivialize the hard work that goes into actually making art? Clayton does not explicitly pass judgement on any of this, but she puts it out for us all to consider.

Clayton took an abstract artwork with obscure meaning by a revered sculptor, Brancusi, and came away with two well thought out critiques of institutional representation. Using wit and a bit of humor, Clayton questions who arts institutions represent and value, as well as the way we find value in an artwork’s authorship, ownership, and legacy. Taking inspiration from famous art, in this case, functions just as well if not better than the original. Object Temporarily Removed brings something to the table that Brancusi’s sculpture failed to deliver–emotional investment and critical dialogue. Unlike the original, it’s not difficult to understand the sort of commentary Clayton is making. The work is accessible, poignant, and relatable.

Lenka Clayton also has another socially engaged work in progress, “Circle Through New York,” now through August, 2017. She is making it in partnership with John Rubin and the Guggenheim Museum, which, coincidentally has unearthed its collection of Brancusi sculptures and has them on display in their permanent collection gallery until January 3, 2018.

Object Temporarily Removed is on display at the Fabric Workshop and Museum until July 9, 2017.