Part one in this two-part series deals with conservation and contemporary art.

Throughout the 20th century artists produced work that was performative, dis-embodied, and/or ephemeral. They had various reasons for doing so. Sometimes the subject demanded it, such as performances involving the body, or works such as Nam June Paik’s “Zen for Film,” which was the subject of the book reviewed in the first part of this essay. Some artists had practical reasons–their work didn’t sell and they couldn’t afford to pay for storing an increasing inventory. Another clearly articulated motivation was a rejection of the values of the art market and collecting institutions. For a long time that rejection was mutual.

Then things changed, and those repositories of the material culture of the art world were faced with the challenge of collecting the immaterial, changeable, and ephemeral. This has raised many questions which will only be sorted out over time; it will also need at least some agreement about what constitutes such art, how museums might acquire, preserve and present it and how academe will record and interpret it. The two books under discussion raise the questions within different contexts.

Perform, Repeat, Record: Live Art in History

This volume of essays is a broad and thoughtful investigation of how the history of performative art should be documented and studied. Authors include scholars from art history, visual studies, theater and dance, as well as curators, critics and artists. The second of the book’s three sections brings together earlier texts that responded to important performances as they occurred, and contributions from artists. The authors offer varying attitudes towards the form, its reception and its documentation. They examine crucial questions, such as the status of re-performances and the weight that should be given to contemporary accounts.

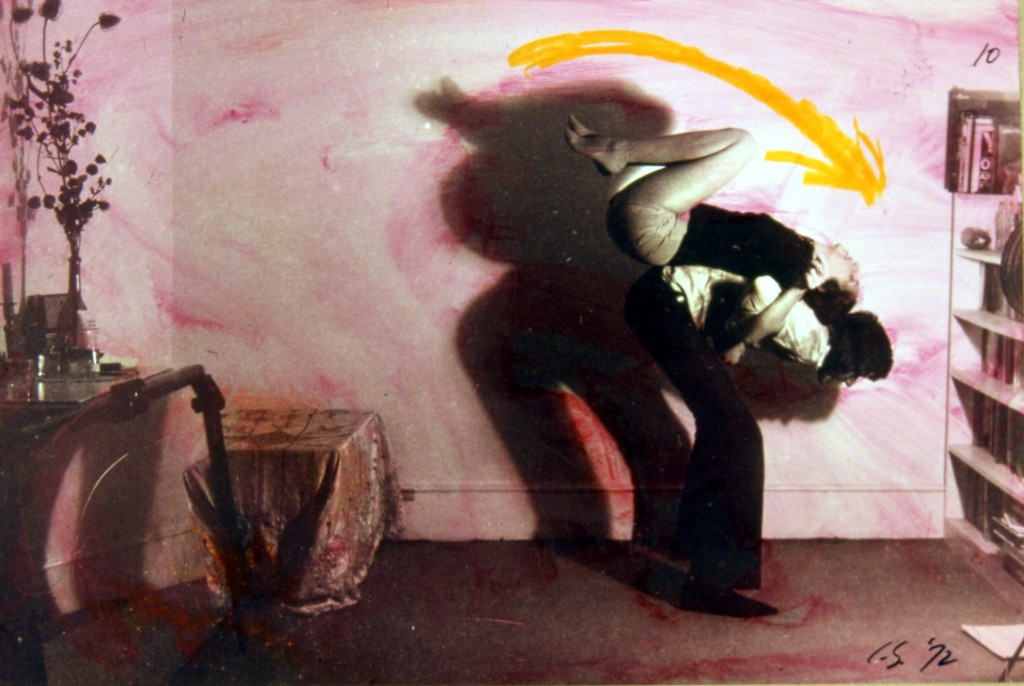

Curator Christopher Bedford cites the 1993 statement by performance scholar Peggy Phelan that “Performance’s only life is in the present. Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance.” Bedford contributes his own caveat: “There is no performance outside its discourse.” Art historian Mechtild Widrich examines the relationship of photography to performance; does it document performance, is it a necessity in order for the act to be a performance, or is it itself a performance?

The book covers a particularly international scope, with essays devoted to performance art in the U.S., Western Europe, South America, China, the Middle East, Australia, and the Soviet Union, including a timeline of Soviet and Post-Soviet performance and another of performance historiography–that is, surveys and re-performances. The final section records eleven conversations between scholars and performance artists, including Carolee Schneemann, Tehching Hsieh, Ron Athey, Janine Antoni and Marina Abromavic.

There is no general bibliography, but many contributors cite useful texts in their articles. The book will be very useful for scholars of performance and can serve as an introduction to the history and questions around the field for performance artists themselves.

Live Forever: Collecting Live Art

This collection addresses the afterlife and preservation of performance art. Its authors are artists, curators, collectors, critics and scholars. They accept, but differently interpret the fact that live art is certain to survive–in memory, language, and sometimes in objects. Curator Catherine Wood looks at the move of museums from programming live art to collecting it. Another curator, Béatrice Josse, suggests that the entire system of values behind museum collections is questioned when performance enters the collection. Choreographer and performance artist, La Ribot, questions what is lost when live art acquires a value and is recognised.

The authors all accept that there are no clear cut answers to the questions involved with collecting live art. Artist Tania Bruguera suggests that each work demands an individualized methodology. She also brings up the point that now that museums have begun to collect live art, there is danger of domestication–that acceptance shapes the limits of transgression that young artists apply to their performance.

For readers who like a puzzle, the contribution by philosopher Jose A. Sánchez takes the form of eleven pages of text, front and back, printed in different type and paper from the rest of the volume and inserted throughout the other essays. He has also included cards that somehow relate to the parts and contain a secret. I did not discover it.

The contributors represent the range of stakeholders who will necessarily be involved in setting the standards, now that live art has become collectable.